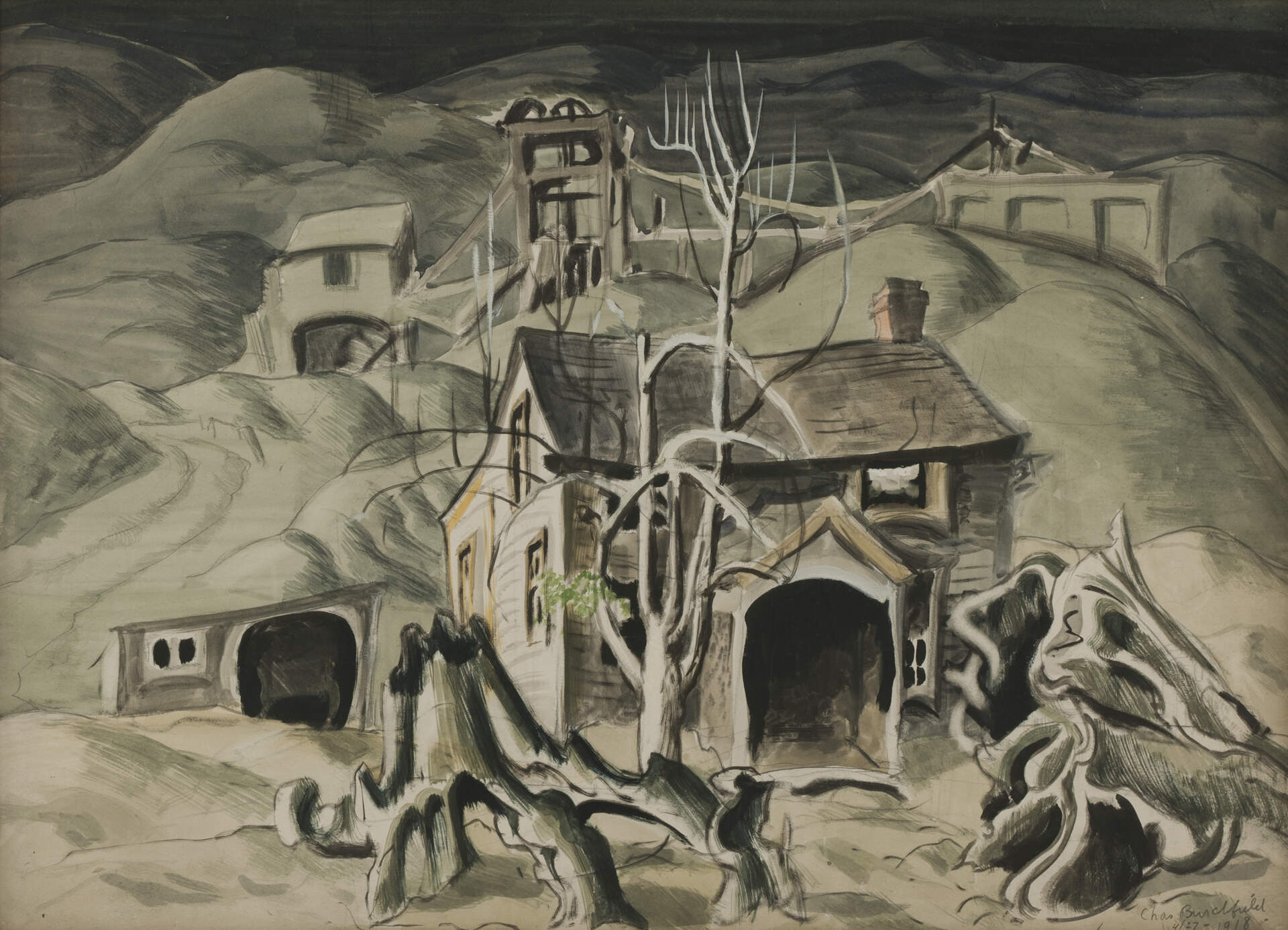

Charles E. Burchfield (1893-1967), Deserted Miner's Home, 1918; watercolor, gouache and pencil on paper laid down on board, 18 x 24¾ inches; Burchfield Penney Art Center, Purchased with support from the Collector’s Club, John and Carrol Kociela, and the Burchfield Penney Art Acquisition Endowment, 2014

Deserted Miner's Home

Past

Dec 12, 2014 - Feb 22, 2015

After a heralded opening at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, the collaborative exhibition Exalted Nature: The Real and Fantastic World of Charles E. Burchfield brings to Buffalo extraordinary works from museum and private collections—many of which have never before been exhibited in our city. This special survey of Burchfield’s art explores the development of his unique visual language which communicates a natural realm full of seasonally brilliant or subdued colors, palpable sounds, and flights of fancy that might alter forever how you see the world. Of special note, the Burchfield Penney Art Center’s recent acquisition, an eerie painting from 1918 called Deserted Miner's Home, is being shown in public for the first time in the Charles E. Burchfield Rotunda in a distinct section of the exhibition that illustrates the development—and continuation—of his brooding and anthropomorphic themes.

Reflecting back on his career in 1965, in celebration of “Fifty Years as a Painter,” Charles Burchfield wrote about the ideas he prioritized and the development of his distinctive style and subject matter. The year 1918 was one of transition, following more than a year’s independence after graduating from the Cleveland School of Art. Unencumbered by teachers, curriculum, and critics, he had reveled in a highly imaginative period in 1917, which yielded his seminal symbolic language of Conventions for Abstract Thoughts and audio-cryptograms. One example of how he could turn a mundane scene into a magical vision is View From Our Front Porch at Salem, Ohio, painted on May 23, 1917. Stimulated by a late May “thunder shower with snow” that defies the season, Burchfield painted a blinding white light with an irregular yellow halo rimmed with pink and green that doubles as a blinding sunburst and a clap of thunder. Pelting rain and heavy snowflakes driven by a brisk breeze mix with the artist’s observations to the east of nearby trees, sky “misty like dissolving snow,” and the “rattle of leaves” that frame the activity.

Modernist ideas permeated his work in the form of “conventionalizing” subjects through simplification, abstraction, dramatic expression, and stylistic borrowing from Japanese prints and other sources. The broad brushstrokes in the multi-layered sky in Countryside Panorama at Sunset, for example, mimic the skies in Hiroshige’s 19th-century prints of Edo, Japan. In Burchfield’s watercolor, farmland, rolling hills, and tree groves can be discerned from simple patterns in transitioning tones of lavender, beige, sienna and umber as they poke through the melting snow. His ideas were reflected through the lens of landscape, without humans, so the picture could tell the story of human intervention with nature without literal presence. His retrospective description of the first half of 1918 explains the context within which Deserted Miner's Home was created:

From mid-January until the time of my departure for the Armed Services, my main interest was Humanity, not Nature. It was a bitter winter. I tried to show the hardness of human lives and the struggles, which naturally led into making “portraits” of individual houses, designed to show just what sort of people lived in them. Many were social or economic comments (Miner’s Huts, workmen’s homes overshadowed by shops, Black Houses, etc.). In others I tried to express the ingrown lives of solitary people. I made a “dummy” for a project picture, which would show all the social and economic strata of a town; it never got beyond that stage, however, much to my regret.[i]

Anthropomorphism was the means by which Burchfield portrayed this environment. Flowers wince, trees join hands to dance around a pond, cliff walls glare in stoic silence, and, as he stated, domestic dwellings take on human characteristics of their inhabitants. Deeply hollowed porch shadows, sagging rooflines, and distressed clapboard turn houses into gargantuan animated beings. Curtained windows became sad or frightened eyes. The Cat-Eyed House is no longer a modest architectural structure in Washingtonville, Ohio; instead it has been transformed into an impatient feline, lurking behind the façade, waiting to pounce into the snow-drifted yard. Sensitive to pets’ personalities, Burchfield may have painted a neighbor’s house in the form of its mischievous cat, which may have sparred with his own cats Toby or Bedelia, from his childhood and youth. (He also had dogs Roger and Teppy.)

Deserted Miner's Home, however, is more than a characterization of an inhabitant. Its forsaken appearance is a reflection of the death of the polluted landscape in nearby towns. Salem had Solomon’s Mines, which were abandoned. The B. F. Lewis Coal and Iron Company in what Burchfield called “Miserable Teegarden,” just four miles away had “extensive deposits of kidney ore” which were “mined and shipped on the Erie Railroad to the Cherry Valley and Grafton Furnaces at Leetonia and the Rebecca Furnace at McKinley Crossing near Lisbon.” Other mines were operated by the West Pittsburgh Coal Company near Teegarden and the Sterling Mining Company in North Lima. The mines and their surrounding landscape, including the flame- and smoke-spewing, in-ground coke ovens in Leetonia and hillside workers’ homes, became a special focus in 1917, 1918, and after he returned from a stint in the U.S. Army in 1919. “I was obsessed this spring with exploring abandoned coal-mines,” Burchfield noted decades after his foolhardy 1919 adventures. “The chances I took were idiotic– It really is a wonder I escaped without serious injury or death— However, it was fun at the time —”[ii]

In Deserted Miner's Home, painted April 27, 1918, the “raw shattered landscape” and bleak, dangerous lives of coal miners are manifested in colorless hulks of a house and shed howling with emptiness, like their former inhabitants—and like the threatening Convention for Abstract Thoughts named Dangerous Brooding that resembles an ominously clenched hand. White tree skeletons illustrate the loss of fertility in a ghost town left on a barren hillside. A miniscule cluster of pale green leaves incongruously clings to one branch, exaggerating the futility of the tree’s last gasps for life in the ashen, gray world. Gigantic tree stumps resemble hulking dinosaur remains, speak to the long era of destruction that killed off, and drove away, any living souls. Only desolation remains after the earth gave up its resources and downtrodden coalminers relocated in search of employment.

A similar gloomy intensity also appears in The Turn in the Road, painted about five weeks later on June 2, 1918, shortly before Burchfield was drafted into the U.S. Army. While utilizing stark contrasts to dramatize lingering fears and irrational emotions established during his youth, he also represented apprehension about military enlistment during the fourth year of World War I. Enormous, unexplained bright white lights shine from a gloomy copse of trees. As if reflecting on his own situation, Burchfield posed a question on the back of this haunting painting: “A lonely house in the woods, sleepy-eyed — dreaming — around the turn in the road lies — what?” As far as he knew, his future had every chance of being cut short by premature death. Luckily, the war ended while he was serving as sergeant in the Camouflage Section at Camp Jackson, South Carolina. He never went overseas.

The somber economic climate of post-World War I America gradually steered Burchfield toward producing less scathing critiques than he painted in Deserted Miner's Home, although he still explored the use of certain archetypal buildings and he tried to keep active a healthy level of righteousness. In early 1922, for example, after having moved to Buffalo, New York, he sketched and noted: “Sanctimonious Houses – yawning mouths – crudely drawn – Beware of falling into a mode of life which would cause you to see the world thru rose-colored glasses. Despise your work & surrounding with the healthy uncompromising hate of idealism— do not lose sight of your initial purpose & impulse to create powerful conventions of nature & human life—”[iii]

In Exalted Nature, the large composite painting called The Glory of Spring shares space with Deserted Miner's Home, in part because of its diametrically opposed presentation. A centrally positioned, abandoned, weathered shed is surrounded by natural elements that are bursting with life. Burchfield had a life-long fascination for meagre dwellings that he believed to be inhabited by individuals who cultivated their solitude. For example, consider two versions of his 1919 Haunted Evening, which was based on “a reminiscence of South Carolina where I spent six months in the Army.” Two black, skull-like sockets stare alarmingly over the hills in one tiny version (just 3 13/16 x 5 ¼ inches) that he gave to his wife, Bertha, as a Mother’s Day present in 1961. The 18 x 25-inch version of Haunted Evening depicts “A man coming home to his little cabin, carrying his sack of provender, fearful of the eerie, haunted, skull-like woods that stands behind his home, against a lurid sunset sky.”[iv] The theme—a solitary man who chose to extricate himself from society and sustain the vicissitudes of nature—recurs in romanticized renderings, most often in later years, without the presence of the human figure.

Between 1919 and the 1930s, Burchfield’s vision of an abandoned shed morphed into a more lyrically poetic symbol, aligned with inspirational ideas from Thoreau’s Walden, which he first read during his late teens and early twenties. The Glory of Spring started as The Shed in the Swamp, in 1933-34, as a more subdued, calm composition measuring 28 ½ by 40 inches. The original scene came from an Ohio site near an old coal mine, but the later version incorporated elements 5-1/2 miles east of Gardenville, New York that he called the “’Shed in Swamp’ Woods.” He returned there in October 1936 and experienced autumn with the same sense of wonder that inspired the earlier ode to spring, writing:

Cool wind blowing out of the sunlit western sky, driving scattered clouds before it. As I went over the rough fields I realized all at once how good the earth was. I stooped and stroked the dry grass and weeds – what a wonderful thing the sense of touch; I squeeze clumps of the weeds & grass to get that feel – the actual contact. Walking on I likewise folded with my arms, a maple branch rejoicing in the sharp twigs and the resisting quality to the stiff branches.[v]

One wonders if there is any connection to How to be a Hermit by Will Cuppy, an Indiana-born author who studied at the University of Chicago, moved to New York, but could not make a living, so he moved further east to the remote south shore Jones Beach Island. As evident in his title, he lived eight years “in a shack made of tarpaper, clapboard, and tin, which he called ‘Tottering-on-the-Brink,’ before being forced out by the Coast Guard when Jones Beach State Park expanded. Back in Manhattan, he published his memoir in 1929 and How to be a Hermit became a best-seller. Compassionately and humorously he wrote: “A hermit is simply a person to whom civilization has failed to adjust itself.”[vi]

In 1955, Burchfield decided to build upon his original composition of The Shed in the Swamp to include many signs of a burgeoning vernal equinox. He reported in 1956 that, “These are the things I love about early spring, and this is the kind of place I love. It is not a particular spot, but the synthesis of all such neglected places.”[vii] He added many colorful elements to the originally austere scene, including red leaf covers dotting outer birch branches like burning embers, golden catkins dangling from the more fully articulated beech tree, velvety chartreuse and viridian moss-covered logs, spritely white and purple-striped spring beauties, and a brown mourning cloak butterfly whose wings are edged with yellow, black and blue spots. Importantly, in the sky, he added a sunlight-rimmed crescent of sky. The shape was a later manifestation of the Convention for Abstract Thoughts for Melancholy/ Sadness, which he expressed as a simple, inverted black crescent, like a pouting mouth. He had told his friends, Dr. and Mrs. Theodor Braasch, “The crescent shape differs in meaning of course according to its position.” When it was turned up, resembling horns, it was “eerie or menacing — at best a pixie mischievousness;” and when it was turned down, it “can express astonishment, wariness, foreboding, and also sadness, nostalgia, or worship of God (as in the new picture with the ‘Cicada church tower’ heat and its discomfort.).” As with all his conventions, they emerged semi-consciously. He added, “That much of my work is self-conscious—but how and when they are to be used is more or less spontaneous; unplanned, and intruding on their own power.”[viii]

What better way could he transform a painting started during the depression years to convey the remarkable optimism he felt at a highly successful time in his life, when John I. H. Baur was organizing a major touring retrospective that would premiere at the Whitney Museum of American Art in January 1956? The Glory of Spring was both a celebration of seasonal resurgence and a proud self-portrait filled with iconic nature symbols. In the center, a pair of crows are perched in trees that reach toward one another. Crows are among the first to nest in late March and commonly mate for life; so they, like the two trees that support them, represent Charles and Bertha’s commitment to each other in marriage and their mutual love of the land. The radiant crescent canopy above them emanates a spiritual hopefulness. Thus, in its exclusive showing at the Burchfield Penney Art Center, The Glory of Spring joins the other magnificent paintings and drawings to reveal Charles Burchfield’s exalted vision of nature.

Nancy Weekly

Burchfield Scholar, Head of Collections and the Charles Cary Rumsey Curator

[i] Charles E. Burchfield, “Fifty Years as a Painter.” Charles Burchfield: His Golden Year—A Retrospective Exhibition of Watercolors, Oils and Graphics. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1965, p. 23.

[ii] Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, Vol. 32, after March 30, 1919, insert after page 41, in later handwriting.

[iii] Charles E. Burchfield, “Early 1922,” Charles E. Burchfield Foundation Archives, Gift of the Charles E. Burchfield Foundation, 2006, Inventory no. 510.034

[iv] Charles E. Burchfield in John I. H. Baur, Charles Burchfield. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1956, p. 38. He lists son Arthur as the recipient in his Painting Index, but the current owner reports it had been a gift to daughter Martha and her husband Henry Richter in 1956.

[v] Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, Vol. 40, Oct. 10, 1936, p. 23.

[vi]The Writer’s Almanac, August 23, 2012

[vii] Charles E. Burchfield, in John I. H. Baur, Charles Burchfield. New York: Macmillan, 1956, p. 68.

[viii] Charles E. Burchfield, Signed autograph letter to Dr. & Mrs. Theodor W. Braasch, September 13, 1959, p. 3.