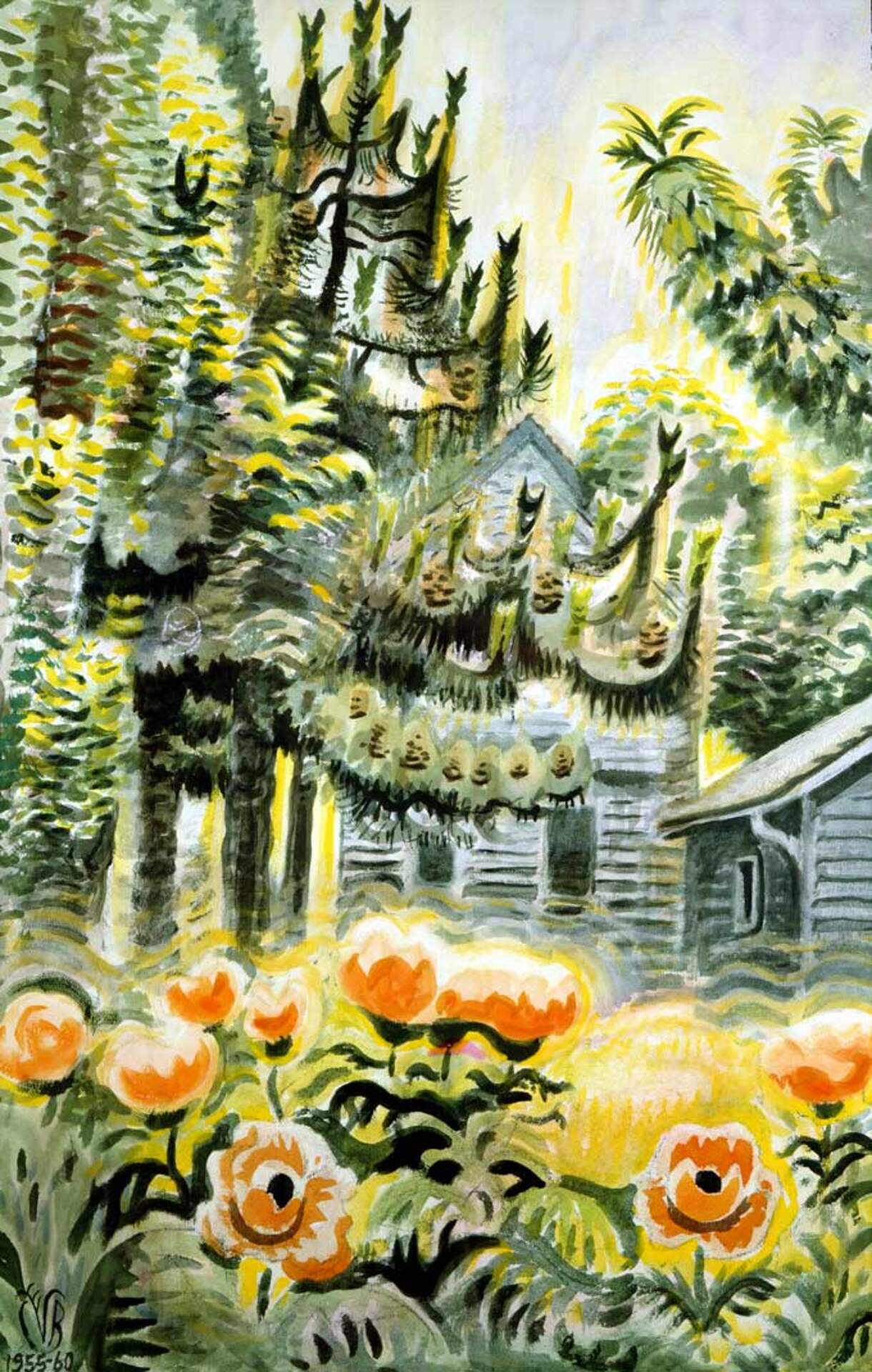

Charles Burchfield: Pine Tree and Oriental Poppies

Past

Jun 11, 2010 - Aug 29, 2010

Over time one comes to realize that the majority of Charles Burchfield’s paintings are memories

that have been triggered by an object or an event and then retold, especially later in life,

with nostalgic reflection or theatrical drama. Pine Tree and Oriental Poppies (1955-60) is a beautiful

rendering of weathered clapboard buildings enveloped by pine and beech trees that contrast with a

stand of red Oriental poppies. Brilliant yellow sunlight pours down from the sky, reflects off leaves,

and saturates the air throughout the scene. Golden yellow heat waves undulate above the

poppy petals, between dark, slender tree trunks and in a small triangular pocket of air where the

shed’s roofline intersects the side of the house. Such bright colors typify a brief period in late May

or early June when perennial poppies open in a showy display of huge, fragile petal cups

surrounding black eyes that will transform into a distinctive pod encasing hundreds of miniature seeds.

What a joyful moment to capture. The flowers, trees and sunlight overpower the modest,

ash gray structures as if to say the earth will persevere while the imposed human mark will fade.

Taking a closer look at the dour buildings, we might surmise that they are uninhabited because of

their black, unreflective windows. There are no signs of caretakers. Past residents did not bother

to paint the clapboard, hang shutters, or install window boxes to cheer the façade. There are no

welcoming lanterns. Instead, the abandoned buildings fade into the background. Yet, they might

be a late manifestation of a recurring subject. In 1924, Burchfield came upon a farmhouse nestled

by pine trees in Cherry Creek, New York. It reminded him of a rickety house in Teegarden, Ohio

near his grandmother’s home that he had explored as a child with one of his sisters. It had an

anachronistic porch with a boarded-up archway and missing columns. Each house had a charming

hidden character and mysterious history. Burchfield combined their traits for the farmhouse in his

painting Evening (1930-32).

It fills most of the middle ground, while three elderly people sit in rocking chairs on the front lawn

between two tall pines, one full of green needles and the other nearly dead. The title overtly refers

to the trio’s station in the “evening of life,” which appears rather bleak. At this time in his life,

Burchfield rejected “becoming an orthodox Christian,” refused to join his wife’s church, and “often

wondered” if he inherited his “strong distaste for orthodox religion indirectly from [his] father, who

naturally turned bitterly against it, having it crammed down his throat daily.”[1] Death’s finality might

only be made more palatable by finding one’s place in nature.

Burchfield reworked the scene for Sunlight Between Two Pines (1957). The lower extension of

the Cherry Creek house has three windows with shades and a door. Steps, a paved path and stoop

lead to the front door, making the residence more welcoming. A small, circular garden to the left

is surrounded by stones. Queen Anne’s lace—one of his favorite flowers—fills the foreground,

punctuated by teasel. His former focus on “Old Age” is replaced by sunlight glowing between the

heavy boughs of two stately pines. Sharply defined, upwardly curved crescent spaces between their

branches resemble some of Burchfield’s 1917 Conventions for Abstract Thoughts defined as Menace,

Fascination of evil, or parts of Morbidness (Evil), Morbid Brooding, or Fear. Over several decades,

Burchfield altered some of the original shapes and meanings. For example, he differentiated

between upward and downward crescents. The pine apertures, which Burchfield occasionally called

“tree spirit eyes,” now were “eerie or menacing—at best a pixie mischievousness.”[2] To the left,

a gargantuan spider perches on top of its web-covered tree. Notations on a related sketch describe

“the mystery of black depths of the woods” in the background. Despite first impressions suggesting

that this scene is more inviting, something sinister lies waiting for an innocent visitor. The year

Burchfield painted this, he suffered unexpected illnesses. He spent three weeks in the hospital with

a bleeding ulcer, followed by “a hideous nightmare of the worst onslaught of asthma yet –”

Recycled imagery can be traced in the albums and folders of studies Burchfield referenced to initiate

fresh new formats for his large, late paintings. Plotting the masterwork, The Dawn of Spring,

he sketched lively crescent shapes amid pine needles and pine cones. Branches reach skyward like

human arms, with the same curvature of the Fear convention. A notation reminds him to

“use the pine tree convention of the 1955 poppies picture,” clearly referencing Pine Tree and

Oriental Poppies, which was started in 1955.

Poppies are so flamboyant that they rarely appear in Burchfield’s paintings, but he used them in

another work, Butterfly and Poppies which is dated (1950)–1966. This particular dating format

means that he conceived the idea in 1950, but discarded the original painting and returned to the

idea in 1966, based on his earlier memory. The folder containing the study of poppies was labeled:

“Poppy Picture given to Louise,” his sister. Butterfly and Poppies is a cheerful, perhaps nostalgic

painting of a swallowtail butterfly resting on a stand of poppies in a yard filled with sunlight.

In the band across the middle of the painting, a wind-tousled flowering fruit tree stands next to a

row of white flowers which lead the eye to a curious looking, flat-roofed shed. In the background,

wind-bent trees nearly obscure a line of houses and fluffy cumulus clouds are blown into wings.

It is an image of simple beauty found in one’s own backyard.

In 2003, I wrote about Pine Tree and Oriental Poppies for the exhibition, Listening to the Trees:

Burchfield Masterworks from the Spiro Family Collection as “a perfect image for Thoreau’s welcome

sense of solitude.” I observed that “The buildings are safely nestled in this protected setting,

warmed by golden rays of sun that coat every leaf they touch.”[3] I quoted from Thoreau’s Walden

because Burchfield had been immensely influenced by Thoreau’s approach to life and descriptive

texts after he read Walden in 1914, writing empathetically in his journal:

Sunset the yellow light kind. What a miracle that yellow light is, coming as it does, well

after the sun has dropped below the rim of the world. All things become saturated with

yellow light even our thoughts. And so I sit in the saffron air, climbing the heights.

At times I read slowly from Thoreau’s Walden. I bless the chance that sent the book into

my hands. It had always been my intention to read it, but like most good resolutions,

it was put off. From reading it, the doubts that have assailed me: i.e. whether a spiritual

life was to be preferred to a sensual life or not, and like specters—were banished.

Thus as I sat and reviewed in my mind the great possibilities life has in store for me,

my mind became dissolved into the yellow air and was carried by it into undreamed of

heights. Life seemed full of good things.[4]

The following excerpt from Walden well serves the impression Burchfield made in his painting,

Pine Tree and Oriental Poppies:

I was suddenly sensible of such sweet and beneficent society in Nature, in the very

pattering of the drops, and in every sound and sight around my house, an infinite and

unaccountable friendliness all at once like an atmosphere sustaining me, as made the

fancied advantages of human neighborhood insignificant, and I have never thought of

them since. Every little pine needle expanded and swelled with sympathy and befriended

me. I was so distinctly made aware of the presence of something kindred to me,

even in scenes which we are accustomed to call wild and dreary, and also that the nearest

of blood to me and humanest was not a person nor a villager, that I thought no place

could ever be strange to me again.[5]

Soul-mate Burchfield also cherished solitude. His journals are filled with memories of solo

excursions in the woods, dating back to earliest childhood, when, after the death of his father, his

mother and five siblings moved to Salem, Ohio. Fields, woods and streams were a short distance

from their home. His relationship to nature as a place of solace never wavered. As an adult,

Burchfield loved his wife and five children dearly, but he also valued the heightened emotions he

experienced on solitary trips to sketch and paint. There are many times when he would have agreed

with this declaration by Thoreau:

I find it wholesome to be alone the greater part of the time. To be in company,

even with the best, is soon wearisome and dissipating. I love to be alone. I never found

the companion that was so companionable as solitude.[6]

So, we come full circle. Just as the taste of a madeleine evoked Marcel’s lifelong memories

in Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, certain landscape elements conjured up

Burchfield’s childhood memories. He realized his life’s work was to paint these visions so

others might relate to them. As early as 1922, after he had married and started a new life

in Buffalo, he wrote:

I believe that man can ask few things better of life than to come back to former

scenes and find them not only unchanged or dimmed, but in reality more

definite than before.

Shut up in Buffalo I thought of summer evenings at our home; how the late

summer shadows screened the flower garden and pansy & petunias seemed to

have sad thoughts of their own when the mournful church-bells began to toll;

I thought of the gaunt warped clap-boarded houses in mid afternoon sunshine

when the sun stands still and eternity yawns over the wide prairies. I thought of

all the quaint or bitter memories of the small towns I knew and dreaded returning

to them, wondering if they were gone with the death of the former life I led.

Nothing has changed and never will change; it is mine forever.[7]

The power of memory individualizes everyone, yet there are emotions we recognize in the

memories of others. As the unconscious relinquishes both the joyous and the terrifying,

we can appreciate not just the beautiful scene in Pine Tree and Oriental Poppies, but also

the many associations that motivated Burchfield to paint it.

Charles E. Burchfield, signed autograph letter to Rev. Martin Walker, Jan. 13, 1931, pp. 1-2.

Charles E. Burchfield, signed autograph letter to Dr. & Mrs. Theodor W. Braasch, Sept. 13, 1959, p. 3.

Nancy Weekly, Listening to the Trees: Burchfield Masterworks from the Spiro Family Collection

(Buffalo: Burchfield-Penney Art Center, 2003): 15, 17.

Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, Vol. 17, July 26, 1914, pp. 10-12.

Henry David Thoreau, The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau: Walden

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989): 132. Thoreau, 1989: 135.

Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, Vol. 35, Aug, 15, 1922, pp. 60-61.