Charles E. Burchfield: Mid-June

Past

Jun 10, 2011 - Sep 4, 2011

Remnicent of a Walt Disney animation, Mid-June is one of Burchfield's paintings that brings forward a colorful optimism. It was illustrated in an article in the Buffalo Evening News Magazine in 1953 that discussed new techniques employed to create composite paintings. This exhibition demonstrates Burchfield's approach to converting a 1917 painting into a larger masterwork in 1944.

“There seem to be many more tiger swallow-tails this year than is usual. Gorgeous creatures, they are to be seen everywhere, making dazzling effect on wild iris, lavender lilacs, and pink roses. Yesterday two of them staged several battles in mid-air, over the possession of the wild iris clump, a fine sight, and a struggle that seemed to be without injury to either party.” — Charles E. Burchfield, June 13, 1944

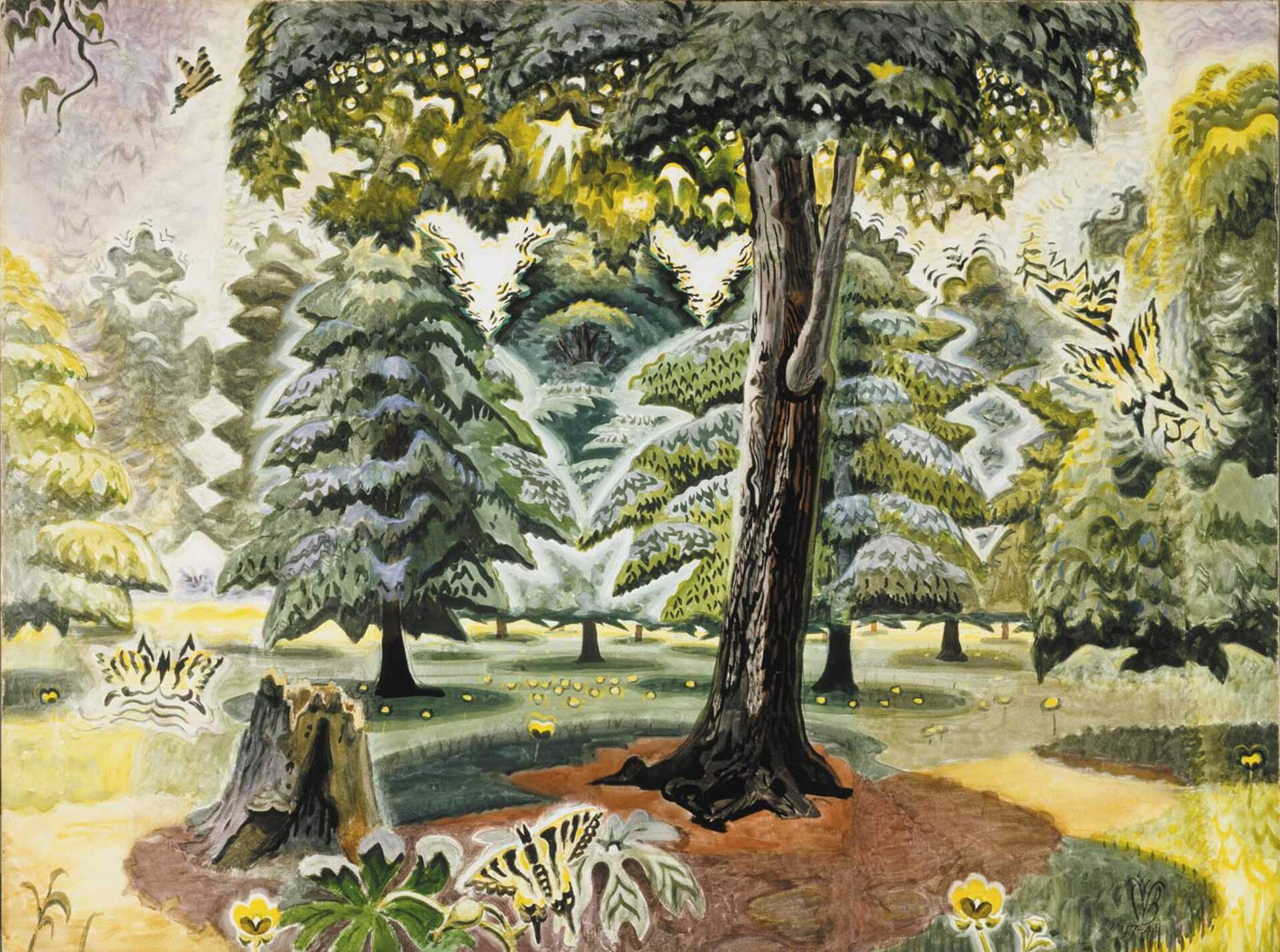

More than any other painting, Mid-June is thought to be Charles Burchfield’s most Disney-esque. While one Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Butterfly seems to be resting momentarily on a foot-wide Mayapple leaf, four others flutter through the air, leaving visual trails tracking their past few seconds of flight. Following their paths, we notice the treetops are quivering from a gentle breeze that cannot penetrate the density of boughs and branches. In the center, the maple tree’s lacy, light-pierced canopy resembles a Tiffany lamp, every aperture sparkling like white and yellow diamonds, birds in flight, and a single star. There is definitely something very magical and unreal in this Wonderland vision that will take closer scrutiny to appreciate fully.

To begin, Mid-June is one of Burchfield’s signature paintings within a painting. It started in 1917 as a vertical painting of trees in Post’s Woods, one of his favorite places to explore near his home in Salem, Ohio. In 1965, reflecting back on Fifty Years as a Painter, Burchfield wrote,

"I have always believed 1917 to be the ‘golden year’ of my career. Forgotten were the frustrations and the longing for more freedom. The big city was not for me. I was back home in the town and countryside where I had grown up, which were now transformed by the magic of an awakened art outlook. Memories of my boyhood crowded in upon me to make that time also a dream world of the imagination."[1]

Among his unique creations in 1917 are Conventions for Abstract Thoughts. Most were titled with ominous names such as “Fear,” “Morbidness,” “Melancholy,” “Dangerous Brooding,” “Imbecility,” “Fascination of evil,” “Insanity,” and so on. However, a few mounted on the album’s pages were left untitled. It’s unclear if their meaning was purposely left ambiguous or unresolved, so one can only guess what hidden meaning lies beneath their application in paintings. Interestingly, among the untitled conventions is a dovetail pattern that Burchfield used on the bottom edges of trees in Mid-June. The deliberately drawn zigzag line can be found in simple compositional studies, as well as the finished painting, where it comes to life as one of many details in a carefully orchestrated study of positive and negative space. The top of the dovetail pattern represents the dark emerald underside of evergreen trees, while the lemon yellow bottom half contrasts starkly.

Originally measuring 22 x 18 inches, Mid-June grew to 36 x 48 inches in 1944 after Burchfield added four sheets of paper around the sides. During the previous year, when he turned fifty, Burchfield reached a turning point in his career. With no hope for sales during World War II, he reviewed youthful works and decided to paint for himself. This is when he developed the novel idea of reconstructing an early painting of a woodland ravine that heralds the change of seasons from winter to spring. In 1943, he enlarged his unresolved 1933-34 painting Two Ravines, from 30 ½ x 47-inches to 36 ½ x 61 1/8 inches. Before he finished it, however, he started the same process on The Coming of Spring, which he had started in 1917. In 1919 he had altered it with gouache, which he regretted and removed in 1931. He enlarged the composition from 30 x 43 inches to 34 x 48 inches. “Reacting against the realism” of Two Ravines, he “finally saw the solution” for a more fanciful treatment in The Coming of Spring and “brought it to completion” in three days. This laid the groundwork for the techniques—as well as philosophical orientation—to reconstruct watercolor paintings as no one had ever done before. On June 13, 1944—the day he noticed the tiger swallowtails—he enlarged nine paintings, saying, “All of these present great possibilities; and I have many more of the 1917 in mind to do —”[2] Mid-June must have been one of the others, waiting on his studio shelves.

There also was a pragmatic reason why Burchfield enlarged paintings by pasting strips of paper around a small central watercolor: large sheets of paper weren’t available during World War II. In a 1953 article that illustrated Mid-June with its five sections outlined in white, he explained, “One day when I was working outside, I suddenly wished I had 6 more inches of space to carry out an idea. Instead of starting a new picture on a smaller scale, I continued on another piece of paper.”[3] As described in the article, Burchfield cleverly slanted his knife when cutting the old and new papers, so the seam would be well disguised by the beveled edge once mounted on board. In this way, he was prepared to “amplify” the idea suggested by the small painting, that he felt “held within its limited scope the germ for a much larger and more complete realization of the original intention.”[4]

It is possible that the animated butterflies were subconsciously inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, which had been the most notorious painting shown in the historic “Armory Show” held in New York in 1913. Burchfield’s favorite Cleveland School of Art professor, Henry G. Keller also exhibited two oil paintings at this International Exhibition of Modern Art, at the invitation of Walt Kuhn. After attending, Keller returned to Cleveland enthusiastic about the modernist works he had seen, and encouraged his students to challenge tradition and experiment in new directions. Burchfield was one of those most liberated by these ideas, writing in 1915: “Keller compared Americans & Europeans as to their freedom of expression. He characterized Americans as being afraid of themselves which is literally true.” Burchfield’s life-long interest in painting all aspects of nature led to his own brand of visual kinetics—such as representing blizzard gales, scuttling clouds, wind-tossed trees, rippling brooks and pelting rain. He also devised audiocryptograms to represent the sounds of nature, such as chirping insects, warbling birds, and thunderclaps, as well manmade sounds of locomotives or factory whistles. In 1944 he must have envisioned ways to break the silent stillness of the original 1917 scene. He returned to an earlier memory and reawakened it in a new era. On one of his studies, Burchfield wrote: “The Sensation of June – It writhes all over the picture – Forget realism entirely.”

While Mid-June was being created, the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy presented Charles Burchfield: A Retrospective Exhibition of Water Colors and Oils, 1916-1943 at the Albright Art Gallery from April 14 through May 15, 1944. It was one of the major exhibitions of the artist’s career, so it seems a fitting gesture that in 1946 the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy purchased Mid-June with the Charles W. Goodyear Fund. In a letter to Gallery Director Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, who had organized the exhibition and written the catalog introduction, Burchfield described their new acquisition:

The original motif or idea, from which the picture Mid-June was developed, was painted in 1917; the full elaboration of the motif was executed in 1944. Prior to this, I had been studying the earlier version. It seemed to me incomplete, but held within its limited scope the germ for a much larger and more complete realization of the original intention.

It is a hot humid day, close to the time of the summer solstice, when the sun at noon seems to be almost directly overhead, sending down its rays so nearly vertical that the light seems to come from all sides and everything seems to be flooded with golden light.

In the foreground is a maple tree, whose umbrella-like canopy of drooping leaves, though pierced by the sunlight thru countless fantastic interstices, nevertheless casts its circular shadow on the earth, forming a sort of cone of shade, surrounded by sunlight. In the middle ground are more trees with similar concentric shadows, beyond which can be seen vistas of yellow buttercup meadows.

Great tiger swallow-tail butterflies, characteristic creatures of June, are disporting themselves, reveling in the sunlight and heat. Out and down they flutter, in nervous restless flight, only pausing momentarily to rest on some convenient mandrake leaf. At times they quarrel and the skirmish presents to the eye a bewildering clash of yellow and black rhythms. Then constant motion seems to set the trees to dancing and the tops of the trees flutter and disintegrate in the hot white sky. Even the buttercups in the foreground assume a strange aspect, as if they were seen thru the butterflies’ eyes. Creatures and plants seem to be intoxicated by the sheer ecstasy of existence on such a day.[5]

Burchfield’s imagined animism of trees and flowers and butterflies experiencing ecstasy is certainly accentuated by his dynamic portrayal of light. Mid-June is one of Burchfield’s earliest portrayals of his distinctive American Luminism in the form of sunbeams, foreshadowing the liquid light he painted in masterworks such as Clover Field in June (1947), July Sunlight Pouring Down (1952) and Purple Vetch and Buttercups (1959). For Mid-June, his “falling sunlight motif” is “full of light, air, pollen, humming of bees.” As it flows onto the ground, “Sunlight at bottom feels as if you could reach out and touch it – It glows as a source of light itself—” The umbrella form of the maple tree channels sunbeams at a slight diagonal which defines two color palettes. Reaching from the canopy to an ovoid shadow on the ground, the contained area seems to project forward like a convex lens, while the sides diffuse away in hotter white light. Notations on a study indicate that the “diameter of all openings” among maple leaves “are concentric with sunrays,” to emit “a sun ray or two” that are “very mystical & evanescent.” This inner space defined by richly hued elements contains about a dozen shades of green. Cool, pale blue-green outlines curious shapes that stand out as mirrored trees, in a style we might compare to M. C. Escher’s figure-ground reversal patterns from the 1930s or Burchfield’s wallpaper designs from the 1920s. The middle boughs of two central evergreens form within negative space two upside-down evergreens—one’s peak touching the dovetail shape of another’s lower edge. Above them, two whiter sky spaces resemble both inverted tree tops and shimmering hearts—as if tree spirits hover in this world from another realm. Added to this, Swallowtails along the perimeter beckon viewers to enter the magical space. In fact, by cropping both the top of the tree and its cast shadow, Burchfield has already brought us into the picture, eager to pick buttercups and chase butterflies before resting in soft shade.

On behalf of the Burchfield Penney Art Center, I want to thank Holly E. Hughes-Bohner and Louis Grachos for granting the loan of Mid-June for this special Charles E. Burchfield Rotunda exhibition. It is our tenth Rotunda exhibition, and the eighth to concentrate on one of Burchfield’s masterworks. (The first illustrated his season transitions and the sixth featured hundreds of doodles.) To encourage our full appreciation of the summer season, Mid-June is shown with two studies from the Burchfield Penney Art Center’s collection (given in 1975) as well as previously unseen studies from a handmade album devoted to Midsummer Caprice and Mid-June donated by the Charles E. Burchfield Foundation in 2006.

Nancy Weekly

Head of Collections and the Charles Cary Rumsey Curator

Burchfield Penney Art Center

Buffalo State College

[1] Charles Burchfield, “Fifty Years as a Painter,” Charles Burchfield: His Golden Year—A Retrospective Exhibition of Watercolors, Oils and Graphics. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1965, p. 20.

[2] Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, Vol. 45, June 13, 1944, pp. 102.

[3] Charles Burchfield quoted in Margaret Hammersley, “Burchfield’s Imaginative 2-Period Paintings — 1917’s ‘Mid-June’ Water Color Enlarged in 1944,” Buffalo Evening News Magazine, January 10, 1953, p. 1.

[4] Charles Burchfield, “Priceless Painting Here For Art Festival, Mid-June,” Photo-News, Vol. 3, No. 38, June 16, 1965, p. 28.

[5] Charles Burchfield, Letter to the Albright Art Gallery May 14, 1946, quoted in Steven A. Nash, Albright-Knox Art Gallery: Painting and Sculpture from Antiquity to 1942. Buffalo: The Buffalo fine Arts Academy, 1979, p. 546; as well as in “Priceless Painting Here For Art Festival, Mid-June,” Photo-News, Vo. 3, No. 38, June 16, 1965, p. 28.