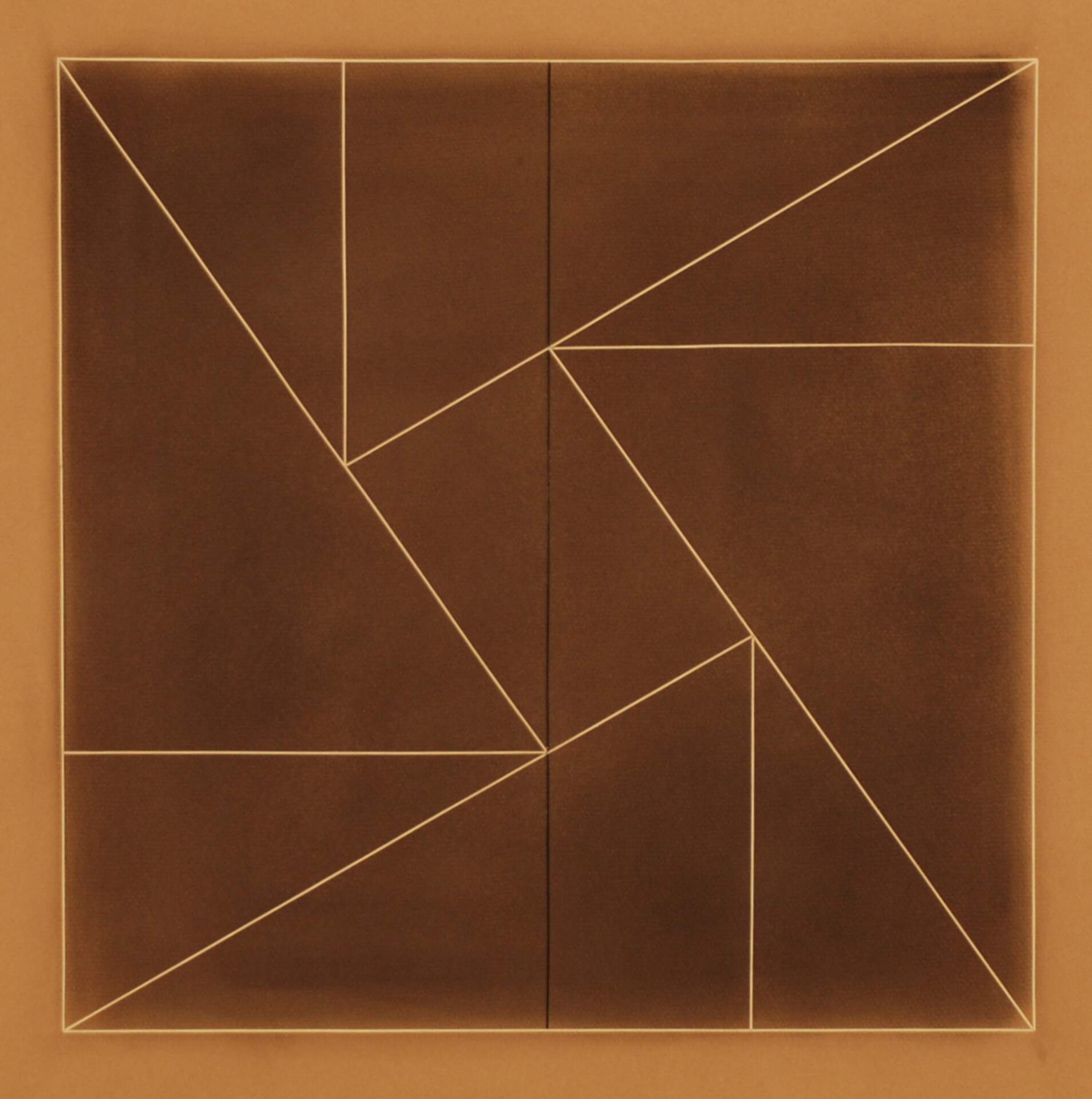

Duayne Hatchett (1925 - 2015), Untitled, 1975; pastel and drafting tape on paper, 25 1/2 x 19 3/4 inches (Frame: 26 3/4 x 21 inches); Gift of the Artist, 1976

Duayne Hatchett: Form Pattern, and Invention, A Retrospective

Past

May 16, 2009 - Aug 30, 2009

For Duayne Hatchett, the tool is more than a mere extension of his hand. It is never a static device, never a one-task instrument. Each tool becomes part of his creative inspiration, generating new ideas that lead to the discovery of new techniques and processes. Whatever the device in hand, the artist is continually on the lookout for novel applications in the production of his art. A give-and-take between tool and process became a natural part of the making of his art.

Like most artists, he has relied on an array of conventional tools in his sculpture, painting and printmaking. But there were times when he realized that the standard tool just wouldn’t do the job. It was then that he went about inventing a tool or adapting an existing tool or piece of equipment to suit his purposes. Over a long career, Hatchett’s use of tools became enmeshed in the studio processes and in countless ways affected the final character of his art.

Duayne Hatchett’s studio is filled with tools and machines of all sorts. There are the Hatchett-invented toothed painting trowels that give his paintings from the 1990s and later their characteristic combed surfaces. There’s a roughly made but precise crimping tool that the artist devised to fabricate the double curves in the strips of thin steel that make up his corrugated lattice sculptures from the 80s . One invented device is devoted solely to shaping ordinary tin cans into sculptural forms. Up against one wall sits a studio-made 20-ton hydraulic jack press built to form the lead bas-reliefs of recent years. It was constructed of found parts, like a piece of sculpture, and in fact, looks like a piece of sculpture.

In addition to the creativity that led to the invention of these specialized tools, Hatchett had an instinct for seeing the artistic potential of equipment and tools that were manufactured for other purposes. An office paper shredder became a tool to create collage material from posters and advertisements.

For Hatchett, the tool determined to a great extent the look of the final art work: the collages were carefully composed horizontal or vertical rearrangements of the narrow paper strips of paper just as they came from the shredder.

In the mid-1980s while visiting a Science Center in Oklahoma City, Hatchett discovered the harmonograph, a mechanical apparatus that employs a pendulum motion to create a drawn image. Hatchett immediately saw the art potential of this “automatic” drawing tool. Soon his studio was equipped with a harmonograph of his own design which, unlike the science museum model, was capable of making very large drawings. The machine consisted of a reinforced working table suspended by four cables from steel beams. Once pushed, the mass of the table allowed it sufficient momentum to continue to move in ever-diminishing arcs. An immobile felt-tip marker affixed to an armature recorded these arcs on a sheet of paper secured to the bed. Hatchett could reposition the pen at will and begin a new cluster of arcs that would often overlap earlier configurations. Visually, the elaborate harmonograph drawings are an engaging synthesis of mechanical markings and expressive biomorphic forms.

Later in that decade, Hatchett discovered the wonderful malleability of lead. He began using thin sheets of lead in his print blocks by pressing and molding processes of various kinds. To Hatchett, lead seemed to hold a seemingly infinite number of artistic applications: patterns and arrangements made with string, bits of metal, pieces of wood, or random objects such as nails, orange peel and bottle caps could be covered with a thin sheet of lead, put into the press and made into permanent bas-reliefs.

Hatchett realized that these thin lead sheets had the ability to carry the most minute impressions, to in effect “remember” the topography of a surface when pressed against a texture or object. The resulting assemblages became art works in themselves or were used to create prints. By the mid- 90s Hatchett was adhering lead sheets directly to the surface of his paintings and manipulating the metal with scoring and burnishing tools to achieve a textural and tactile surface.

The shaped lead and copper bas-reliefs in the Diva series of the late ‘90s required more Hatchett ingenuity. Along with the making of some specialized tools for working the metals, the artist built a wood frame in which galvanized steel shapes created a negative mold. The metal was then pressed into the voids to form the abstract figure.

Of the tools, it was perhaps the toothed painting trowel that proved to be the instrument of unparalleled versatility. Made from steel or wood with teeth of various depths, these simple tools were capable of making controlled and repeatable textured patterns—often in arc configurations—in a pigmented surface. Deep furrows might appear in one canvas, while another might hold the most delicately inscribed arcs. The tool could score the paint forcefully, almost brutally, or it could glide over the surface in a lightly combed gesture. For instance, the strong tonal contrast of Royal (1992) are achieved by means of a hefty trowel with even, wide-spaced teeth, while In Around and Back, 1994, the delicacy of effect is gained through the use of a much finer, evenly spaced instrument.

The crimping tool’s primitive looks belies its subtle shaping capabilities. The device has the ability to imprint just the right bends to the galvanized steel ribbon so the strips can be riveted together into a lattice. The resulting matrix can be formed into a shape that seems to undulate gently before the eye. The effect can be vividly seen in the wall piece, Essex (1985). Hatchett says that trial and error and a little mathematical calculation gave the crimping tool its exacting nature.

Hatchett’s fascination with tools and processes has been with him since childhood. As David Hatchett relates in his biographical sketch of his father, Hatchett’s experience in a sign shop during his college years had great impact on the young artist. For the first time, he had access to a local metal shop, where he could work with steel, sheet metal and plastic, all materials that would play an important role in his future art. It was an experience that introduced him to a captivating assortment of tools, machines and processes. What he learned back in that sign shop would be applied in multiple ways over much of Hatchett’s creative life.

Once Hatchett decided to become an artist, his innovative spirit came to the fore. He never was one to follow standard methodology in his art. In the late 1950s, for example, when he was teaching sculpture and casting at Tulsa University, the young artist began to ponder the ancient art of bronze casting and came up with an ingenious variation on the lost wax process. Instead of wax, Hatchett employed Styrofoam as the material that would, after a lengthy and complicated process, be burned away—or “lost”—by the pouring of molten bronze. For the abstract sculptor, foam had many advantages. It could be shaped and assembled with little effort and varied in an instant. The sculpture could be built up piece by piece in assemblage fashion, or it could be assembled as a unit and then cut away in the traditional subtractive manner. Styro Structure #1 (1957), one of the first of these pieces, is a dynamic assemblage of forms that might suggest a composition of steel plates were it not for the distinctive texture of cast bronze.

Throughout his long career, Hatchett would continually seek new processes and revise old ones to his purposes. In the studio, the artist was often the experimenter, discovering new art-making techniques by manipulating any materials and objects that came his way. Whether working with a standard tool or one of his own inventions, Hatchett would bend it to his will, extending and redirecting its function. Tools and the processes that they generated were not incidental things in the artist’s life. They were the source of profound artistic experiences. They were deeply engrained into his artistic persona.

In “2001: A Space Odyssey,” Stanley Kubrick presents a potent image of how tools are not merely passive objects once they are in the hands of a sentient being. An ape takes a bone and uses it to kill an adversary and then, conscious of the magnitude of his act, throws the bone into the sky. The soaring bone slowly morphs into a space ship; a complex machine capable of extending our ability to travel to new planets…another tool .

This is the perfect metaphor for Hatchett’s view of the tool as a transformative thing. In the right hands, the tool can be made to change and adapt to every new artistic circumstance and, to the artist in the heat of creativity, becomes a trusted and vital collaborator in the multifaceted process of making of art.

-Ted Pietrzak