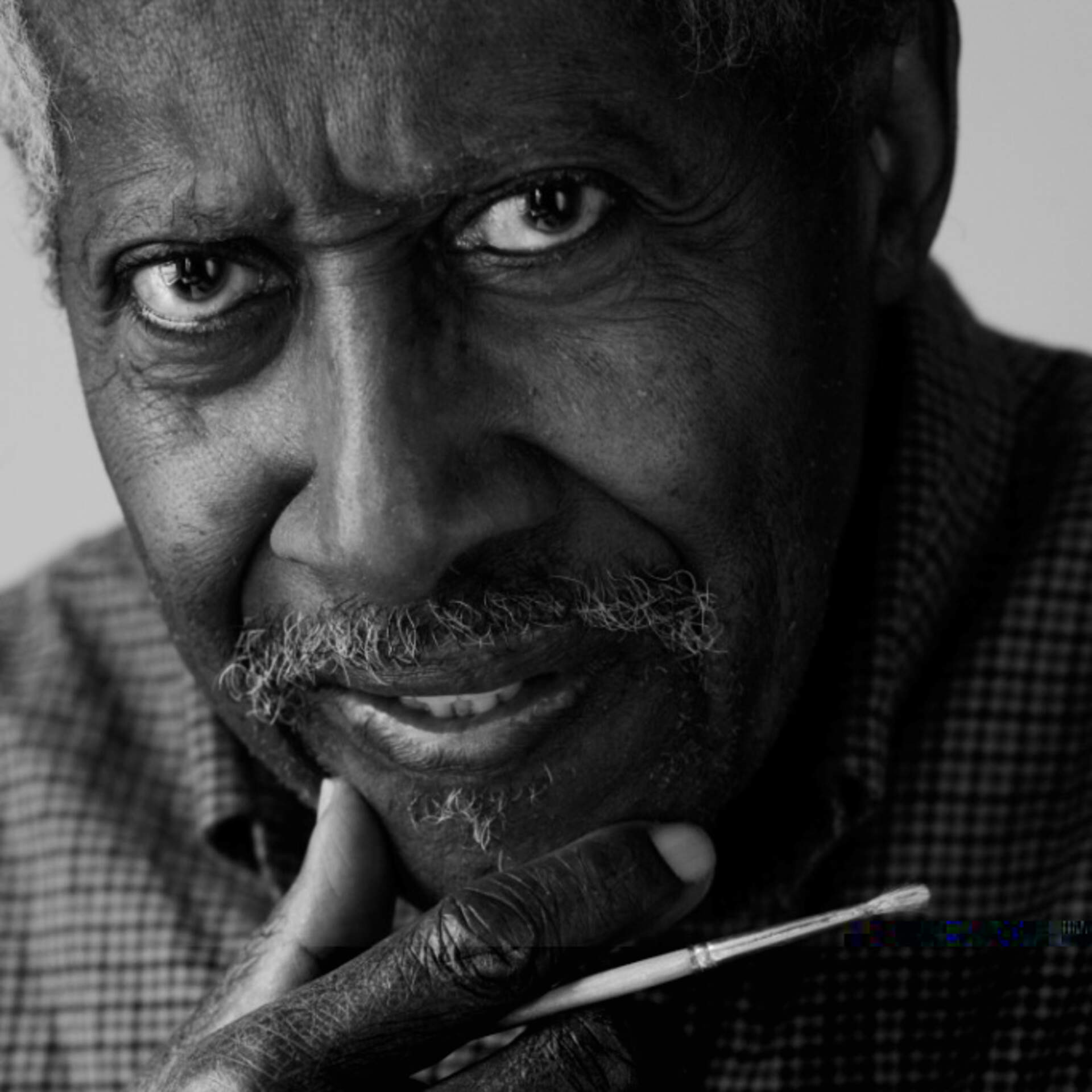

William E. West, Sr.

(1922 - 2014)

American

Born: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.

William E. West is part of the Living Legacy Project at the Burchfield Penney Art Center. Click here to listen to his artist interview or read the transcription below.

William E. West was a Western New York painter whose career spanned seventy years. He was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1922 and moved to Buffalo, N.Y. in 1927. As a young child, he was captivated by drawing, an activity encouraged by his mother. After returning from World War II, West attended the Albright School of Art briefly and then became deeply involved with the Buffalo Arts Institute, where he studied with Robert Blair, David Pratt, and Charles E. Burchfield, among others. West found the latter organization more expressive and less structured, providing varied opportunities to explore materials and the full range of their uses, and he eventually served as a board member.

In an artist's statement, he once observed, "[Throughout] the 70s, 80s, 90s, and into this century, I have used my pen and crayon pencils to record my primary impressions. These actions allow me great freedom when I decide to use these sketches for painting, to rely on memories both past and current in my work. This way I am not burdened with trying to portray reality. Just relativity to time and place. My work is not about perfection. Only relative impressions." [1]

West's paintings have been exhibited at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Wilcox Mansion, Kenan Center, Erie Community College, and the Chautauqua Center for Visual Arts, among others. His work is in the permanent collections of Bethel AME Church, M&T Bank, the Buffalo Urban League, and the Burchfield Penney Art Center.

West retained a full-time job as a postal worker from 1946 until his retirement in 1978. He continued painting until his death on April 14, 2014.

Creating art was always a central part of William West's life. In his Living Legacy Project interview, West notes that "art continued to be something I pursued without an ambition to be a commercial artist or wanting to make money off of it. I just wanted to paint."

[1] William E. West, undated artist's statement.

Listen or read: William West’s interview with Heather Gring of the Burchfield Penney Art Center, conducted on July 25, 2012. In their conversation, West talks about his first interactions with art and copying comics out of the newspaper. After World War II, he attended different colleges to pursue his education. He discusses his development and how he learned to be the artist he ultimately became. A good friend of Charles Burchfield, West shares memories of painting with Burchfield and other well known Western New York artists. Given his broad knowledge of art, West's interview is both informative and inspiring.

Transcription of Living Legacy Project Interview with William W. West Sr.

Recorded July 25. 2012

Transcribed by Katie Gaisser, 2018

HG: William, was there anything you wanted to say?

WW: Yes, initially, I'd like to dedicate this interview to my mother, Mary Henry West, who was my first teacher when I was six years old. She did a drawing of a man in a suit and told me as a single child, I was going to have to entertain myself and so I spent years drawing from such things as comics and Times, Courier, and the news were the papers we had then, and I would carry on with the interview.

HG: William, what made you decide that you wanted to pursue a life in the arts?

WW: Well, I didn't, I never really thought about it as a life in the arts for me. Art is something different for everybody. It was a means by which in my youth I entertained myself. We had found a box of rag-made paper, and the sheets were six by nine inches, and like I said, I copied the comics. In high school, we didn't have TV then, so I'd listened to football games and I'd draw my impressions of the action on the paper and from the comics that I copied, like I said, were Tires and Tailspin Tommy, there was a couple others, but they... Prince Valiant was one of them, they were all naturalistic, so I learned unknowingly how to draw the human body, how to draw houses, trees, vegetation, skies, I really knew a lot about drawing that I didn't know I knew. But it was fun, so when I came home from the service in '46, we had the G.I. Bill, and so I decided I wanted to try drawing formally. I went to U.B. for a year, and then transferred over to Albright night school. This was back in '48, I transferred over to Albright night school. I went one year there and then I was working in the post office. And so I worked the post office at night and I learned that the Art Institute of Buffalo had classes in the daytime I could attend. And so I went there full time. I usually arrived at 9:00, 10:00 in the morning until about 1 in the afternoon when I had to go to work. So, art has continued to be a, something I have pursued without an ambition to be a commercial artist or make money at it. I just wanted to learn how to paint. And I did that there. There was a… I remember there was a Louise Jamison. She taught us how to make gesso panels and canvas panels and so there we began to paint from there. And then I met Bob Blair and David Pratt and a few others at that time and I was impressed with Blair’s work in the sense that I tell the tale that he would come in from his farm in the any given day and if he didn’t have a pallet, he would take a garbage can top, toss it on the floor, put his water colors on the floor, and proceed to do a painting. And so I learned a free spirit. It was a… I knew others who went to Albright were taught a more formal system, but the artists who were sort of free-wheeling. And from them I learned composition and we would maybe have to draw apples from memory or whatnot. We went out in the field a lot. We made a lot of figure drawing and they just added to my passion for drawing at that time. And I just carried on. I’d do that. On days off, sometimes the family would be sitting playing cards and I would draw the family members playing cards. So, I at that time, I worked a lot in oils. I appreciated oils and I began to work oils on paper. I’d been down to Zoar Valley one time on my own. It’s quite a road down to Zoar Valley. And went down in there and was on a weekend I was doing some paintings and I ran out of…something I ran out of. Anyhow, I started doing the oil on paper using the medium {mar varnish} or so forth on the paper with the paints, and I liked the results I was getting, and I kept on doing that. I have a painting I did of my grandmother with a house painting brush. Four inch. Stipples. No one will copy that picture because you can’t copy the stipples. But that’s part of it, and kept on going to, one teacher told me that was a misuse of the materials. In the meantime, being with Bob Blair, you learned oils and watercolor. And I did a lot of watercolors then. And so, later on, I’d say around about ’55, Mr. Burchfield began to teach at the Institute. He liked their approach to art and he’d known them for quite a while. Dave Pratt and Bob Blair. So, maybe a couple of years later, I told him about this experience with the teacher who told me it was a misuse of materials. He said, “Uh uh. You do what you want to do with what you want to do.” And that was important because I just viewed your show out here, The Artists Amongst Us, and you certainly will see a wide variety of styles and uses of color. So, I’d proceeded on, I’d let the oil on paper go, and I had done a lot with pallet knives and brushes and so forth, and I had an accident which from the accident, I couldn’t carry the equipment around for oils so I began to do more watercolors and gradually I began to draw with crayon pencils, and I found that I could take crayon pencils and a small pad and go wherever I wanted to and draw, so I used to go out right in the road and do landscapes out there, I would go to the library and see somebody slouched out in the chairs of the library. I would do them. I enjoyed doing whatever I saw in front of me and how I approached it. So, I had no particular subject that I favored, city, or country. It was all the same. You just respond to it as you as an individual respond to it. My one problem is I wasn’t painting for somebody else, I was painting for me. And if somebody liked it, okay, but if they didn’t like it, I didn’t care. It’s what I wanted to say at that time, or what I could say. I learned later to do other things. One thing I liked about oils was you could do glazes, so you could have a certain amount of transparency. There is transparency in watercolors too, but I found with acrylics, you can handle it both as heavy material, or you can handle it like a watercolor. You can mix the two. So I enjoy doing… when I say mix the two, you can use the material both ways within the same painting. So, I do a lot of things that maybe others wouldn’t do, but I do what I want to do. But that’s the way I always approached, I never approached it from the standpoint of making a living, because I had a good job. I was a postal clerk, and then I became the supervisor when I retired. But you had in the questions that you sent us, “why were we here in Western New York?”

HG: Mhm

WW: Okay, my… I’m a fourth generation in this community. My great grandfather escaped slavery, went into Ridgeway, Ontario, back in 1840. I have from the census bureau, from the census record in Ridgeway, Ontario, that my father was one year old in 1851… no it would have been my grandfather was one in 1851 and my great grandfather was 27. I had two sets of parents. I was born to Loretta Jennings in 1922 in Pittsburgh, and then her sister, Mary West, adopted me within a year later. And so, she brought me here to Buffalo in 1926. So I’ve been drawing since about 1928.

HG: Could you talk about some of your most important influences as an artist?

WW: I’d have to say the comics. I’d also have to say the teachers that I had at the Institute, and I would also have to include a teacher by the name of Joe Fisher, who was at UB when I was there studying under Empire State. With Blaire and Burchfield, and Pratt, there were no rules. You did what you wanted, and if you wanted to work in abstract, that was you. If you wanted to work in impressionistic, that was you. You did whatever you felt that you could do with the particular medium. I guess I was influenced by Blair, and I do have a couple of pieces at home that I did try to do an impression of the Burchfield style, but I didn’t try to incorporate them into my work. They were just people who taught me how to see, and how to put my expression on paper. I had a self-portrait I did. Took me twenty years to finish. I had everything except the color of the collar, and I couldn’t figure out the color of the collar. About twenty years later, I was able to fill in the color of the collar, and the picture came together.

HG: What color did you eventually decide on?

WW: Well it was just sort of a pale gray collar. It was a plain shirt, but the rest of the picture, it took its place in the picture without jumping out as a white shirt. It’s just… that’s something else, you learn how to harmonize, and you develop your own harmonies. I have… my wife used to say she could tell my work, she knew my color scheme, but I didn’t know them. I just painted.

HG: What are some different themes that may have emerged in your art?

WW: I did have some themes as it were. There were about five paintings that I did with sewing machines in them. Both my mothers and my sisters in my original family, and a couple of ladies that I associate with later on, my wife, and another friend all sewed. And so a sewing machine was always in the presence wherever I lived. So that was sort of a recurring theme. In referring to my mother as a teacher, I never saw her do another drawing, but she sewed. There used to be a picnic we used to go to over in Fort Lucy from St. Catherine’s, it was the second Saturday in August. People would come from Toronto, and people would go from Buffalo in the black community who were, either came from the island or immigrated to Canada. So my mother always in August made a gingham gown, not a gingham gown, but a gingham dress and a gingham hat, and I used to, she used to make our, my father and I’s pajamas and stuff like that. So, those were periods when creativity for the woman was in the house. Oh, they cooked. That was a creative art in itself. But the fact that they did so much sewing was an art. And, well, when I first started going to the Institute, at the same time they started building the high rise apartments in Buffalo. And there were a couple of artists elsewhere that made drawings of the framework. So, I remember I did a drawing. I went home and I did a drawing of the framework for the first high-rise on Jefferson and Williams Street. And from there, I did others, other drawings, but then in the 60’s, I lived on Gray Street and I walked home to and from the post office. During that time, I would pass areas that were being torn down. So, there’s one painting I call “Urban Renewal”. The thing was, I wanted to capture the spirit of the properties being burned down as a cheap way of breaking them down for urban renewal. At the same time, I wanted to get that feeling of the fire and the smoke. And I put the furniture in the front to give a sort of relationship to human habitation. And so that was that, and then I did several other landscapes, I did one called “Court Street”. Unfortunately, I didn’t turn around and do the building that was behind me at the time I did it, because the building that was behind me was the old library, and that would have been interesting, but I have another one, I did City Hall, looking from where the old library was down Court Street. I also did one of what was called “Bennet Street” as it looked before the housing came in. It was a red painted sort of combination garage with an apartment above, but in the background is the old church at Pine and Broadway. And so, in some of the work that I did, I would have in the background things that were of the old Buffalo. I did one of the Federal Reserve building as it was being built, and in the back of it was one of the schools that used to be in the Elmwood-Delaware neighborhood, I don’t know what the school was, but I did that. I also have one that I did of 22 East Utica. Now I live at 19 East Utica, which is across the street, and 22 East Utica now is part of the NFTA turn around terminal, and so as I was learning to paint, my mother asked me to do this painting and I did the painting of the house that was there. So that’s sort of the… and also in the back of it, in the back of this house I show the old Glenwood Apartments. So there’s quite a few things that I have of historical sites. Sites that are gone. And community. I wound up painting community and drawing community. And sometimes I drew the people in it, not because I was trying to do a grand portrait, but just trying to draw to others what I saw in a person. I did have… I do have a painting that I did of my wife back in the 50’s and it wound up in the Wayward Muse presentation over at the Albright. Now, the thing with the Wayward Muse was they picked 52 artists from Western New York and I wound up being one of them. Over a 125 year period. So, this is another strange thing with art for me. It opened up many doors that I never expected to be privileged with. Such as like sitting her now. I have never painted for a purpose other than my own enjoyment, yet it has put me in touch with people, such as Mr. Burchfield. And I’ll tell you another one about relations with Mr. Burchfield. I grew up at 19 East Utica. 19 East Utica was sort of the hub between the science museum, the Albright Museum, the historical building. Well, on a Sunday afternoon, a lot of times, I would walk down to Humboldt Park. Humboldt Parkway at that time was a bridal path. And I used to walk over to the science museum, and I’d spend my time going through the science museum. Other times, I would go to the historical society and go through there. And I remember going through Albright, and I remember in school they used to take us in busses to go to these places. And I did remember Burchfield’s paintings, but I didn’t know who they were. I didn’t know who he was. But they did stand out in my mind because of his particular way of handling his colors. You’d never saw… they were always sort of clean edges. There was… I don’t… I’m not aware of much fusing of edges in his work. Most of his edges are clean and sharp and the one that impressed me the most was, he had trees that looked like… I think butterflies. And I looked at that quite often, never thinking that someday I would meet this man. And so, I was impressed with the scenery going through the old Humboldt Parkway, and so I knew what was called the Olmstead Parkway intimately without knowing that I knew them. And I miss them now, I hear they want to go back to that, but they never should have destroyed it. It was beautiful. It was nice seeing people riding horses. They used to get their horses from over on Delevan Avenue. There was a state horse cavalry right behind School 17 there at that time.

HG: Could you talk going out to Robert Blair and Charles Burchfield’s houses?

WW: Oh, Bob Blair lived out on old Leann Road by Blanchard Road. He had a house and a shed. He called it a shed, but anyhow, I’ll bet you when he passed away there were thousands of paintings there. Now I’ll tell you something interesting about one painting he did. Maybe ten years before he passed, he showed me a painting. It was a watercolor that he had left outdoors in the winter so that the frost could make a pattern over the painting that he did. That’s how creative his mind was.

HG: Wow.

WW: It was a beautiful piece of work. And I guess I would also have to incorporate this: back in the 50’s, I was in a community that was not as respected as it is today. And they respected me as a man. All I had to do was draw. And with Mr. Burchfield it was the same thing. I remember seeing a painting that he did. I saw it in a book in North Carolina, and he drew a group of black brothers before a- sitting in front of a community store, but there was not any negative tones in it. It was just fellows sitting around a store talking. And that was Mr. Burchfield’s approach to me. Now I was also told you didn’t get in his house unless his wife approved. We also exchanged Christmas cards. I have- I still have some at home now. And the same with Bob Blair and Jeanette Blair. I have a lot of their cards.

HG: What was it like going over to Mr. Burchfield’s house?

WW: I was a nervy fellow, so I asked him to look at some of my work. And he invited me out, showed me his studio, showed me his easel and everything and then took me into his house. And in a couple of cases, I saw a couple of his masterpieces before the public did. That’s the kind of man he was. He was just a regular fellow. And he accepted me, but I knew we drove out to Blair’s house maybe on a Sunday afternoon. All of them were regular people. I only have met Katherine, I didn’t meet his youngest daughter or his son, but an interesting story that I can add to it is his youngest daughter studied cello, and I studied cello, and we studied from the same man over on Hughes Avenue, but I never knew until later on I had a conversation with Mr. Burchfield and he said his daughter had studied cello from a fellow by the name of Joseph Berlin. I believe in a thing called circles, and you may do something today and somewhere along the line you may come back to that same circumstance or people in life and I’ve had a lot of circles.

HG: So you mentioned that you went from working in oils to working in watercolor, can you talk a little bit about your creative process? You know, when you start to make a piece?

WW: I remember one time my family used to go over to Ontario in the fruit area and pick the fruit. Well, I had my drawing morillo block about 19 x 16 and I had my brushes and oils, so while they picked fruit, I looked at a house and did a painting of the house and the foliage around it. To me, it wasn’t about “I’m going out to do this, or I’m going out…” it would be more like “I’m going to an area and see what I can do.” And it wasn’t the- it’s just a response to the area and what I could do with it. It‘s hard for me to pin down a style. My style might be more impressionistic. I was not trying to compete with a camera, no way could I, I was not trying to copy somebody else’s style, I just put down what I saw, what I felt. There’s one you have here of 254 Broadway. Now that 254 Broadway was a place I passed by every day when I was going to work when I lived on Grays Street when I worked at the main post office, which is now ECC. I was impressed because when you look back in a sort of a passageway from the street, into the back, you would look back and see another part of that property with wooden stairs going up to an apartment. I got the impression that at one time, a carriage- they kept horses back there, and maybe a carriage. And the- whoever took care of the horses and the carriage brought them through that space. And so, you might say it wetted my imagination as to what that could have been. And so, one weekend I took my water colors and went up there and did that, but it’s hard for me to define my own work receptive with my reaction to what I saw, and I wasn’t trying to copy anyone else, I was just doing what I saw, what I tried to capture.

HG: You have lived in Buffalo your entire life.

WW: I have been here since I was four. So, I know Buffalo, rather I did know Buffalo, it has changed quite a bit, but I did know Buffalo.

HG: I was just going to ask, you know, even thou you really didn’t pursue a career in the arts, how has the arts community helped you find your path? And you have touched on that talking about the Arts Institute, talking about Blair and Burchfield.

WW: Other than my relationship with the people at the Burchfield, also I had a relationship with the people who founded the Langston Hughes papas [SPELLING/WORD], and a few of them. I really didn’t get involved with the art community itself. I didn’t strike a lot of their fancy. When I say I didn’t- I didn’t sell a lot of work, partially because I guess I was working, and there are other things involved in art, sometimes besides art. There’s the political side, and I never got involved in the political side. So, I would have to say that my relationship with the institute opened up more doors for me than anything. But since then, I have through, I sort of knew Ted Piercig [SPELLING] pretty well. I guess another thing in the historical- going back in the historical part of paining, I did some things that were landscapes in the Elicott district. One was the original Bethel Church which used to be down in the Clinton Street area. They’re now out on Michigan and Ferry, but I have a painting I did of them of their entrance to the old church back in the 50’s which they have. I did a study, and my paintings to me are more like studies. They’re not like finished paintings. I did one of- at the time the emergency hospital, which used to be on Pine and Hickory I believe. At the time it was being torn down, my mother was living in the Perish Street Projects and I used to go down and take care of her and they were tearing the building down, and I did a drawing of that and later converted it into a crayon drawing, and the Urban League purchased that from me. But those are samples of things I did in the community that people would relate to. So, I did things that I perhaps don’t even realize that I did that related to places the community was in. I was not zeroed in totally by community, but community was around me and if something struck my fancy, I did it. I fancy myself as a community… trying to do community improvement, and I suppose I would rate it as a thing that improved my understanding of people. It also improved my understanding of economics because I understood economically, the inner cities are not manufacturing territories, and this would be getting into the economics of the nation as a whole. Your inner city communities don’t make products. They buy products, and often the people who produce the products don’t want to see them be given grants, etcetera, but they don’t understand that their profits come from the inner city people who can’t produce buying their product. Now I was introduce to that concept. I used to work with my post office credit union, and at the time when I was working with them, they sent me to Cornell University for summer workshops. And one of the fellows who came there to teach us at the Cornell workshop, and you figure most of us would have had jobs that were dealing with credit unions- these were credit union workshops, so therefore, money wasn’t a problem, family structures, etcetera wasn’t a problem, and he came there and opened my eyes to something that I didn’t realize others realized. We often criticize people on welfare. At that time, I had a – you’re taking me off in a political direction - but I had the concept that the culture of the country destroyed family life. When I came home from the service, the fellows that came home from the service built up the cultural security of the country by taking jobs, but the women that became our wives, and had been our mothers had worked in the factories. So this meant - this is my eyesight – this meant that the manufacturer and the finnessier [could not make out word] saw that we were saving money they didn’t want us to save. So he began to make products that we wanted. Well yes, we bought homes and built our families and so forth, but it also took up the money that we might have saved ourselves. And also, the idea with the welfare department that a man could not be in the house, and the woman received welfare support. So this broke up families. This meant that the family left- that the husband left the family structure in order to see that his wife could have income because he had no job. So then from that, I- this fellow at Cornell, told us, you know, he says “You’d be doing the same thing as they’re doing” he said, “because once you’re through with the income from the welfare, you wouldn’t have enough to buy anything else other than what you immediately had to have.” You didn’t even have enough to go to work. And you’ll see families now that are shown on television that hardly have enough to go to work. Even working families are out there getting food stamps, which is not right. With Echo, we did start out trying to build a cooperative. Now yes, I took off on a tangent, because this tangent was what led me to Echo. The fact that this man explained to us about the welfare families. Alright, so I came back – this was in the 60’s when Martin Luther King was marching and everyone was trying to figure out how to build up the community. So I took some fellows from the post office and we used to go out to Clinton Street Market, and we put groceries together. Buy groceries and take them back to a center, my wife and some women would gather and put them into bags and we’d sell them for five dollars. We’d have like a five pound of potatoes and five pound of apples, and maybe three or four pounds of meat in them and greens and canned goods and sell them on the weekend. People would order them, and we’d set up centers. Then along comes this program “Model Cities”. They liked our program, so they wanted to back us up because we- and said they would help us with our program, so then we began to think about the idea of building up a community market. A cooperative. Well I understood cooperatives because I was already working with the post office cooperative. And so the idea there was that you- we’d sell them shares for five dollars to people in the community, but they really didn’t understand that because it had not been part of their education. And I think we had two sites. We were originally set up at 333 Williams Street, and then we went over to I think it was 975 or something like that at Herman and Genesee and built a market there. And we sold food at the same prices as the other place, but because of- I would call it brain washing- the people could not understand that we had the same products, and they thought we were in business for ourselves. They didn’t understand the cooperative idea. So, eventually we faded out, but that sort of distracted from my art too. I guess I come from a family that was always trying to do something. You know, my daughter was head of the municipal housing for ten years. At that time too, United Church of Christ, which we had joined was heavily involved in community development. So I had the support of the- what do you call it- the United Church of Christ and the council of churches in Buffalo. So I had a lot of- again things that I would have never would have thought of doing. But one thing led to another.

HG: I have one more question for you.

WW: Okay.

HG: My last question is, what advice would you give to emerging artists now, to students who are maybe graduating from college, they’re starting their art career.

WW: A lot of it depends on what their goals are. If they want to be a commercial artist, fine. If they want to be a fine artist, fine. It’s hard for me to say because I was neither. I remember once I was asked to speak to a group of students about art and I realized when I went to approach them, I couldn’t tell them how to be a commercial artist, because that wasn’t my interest. Yet- But I will say one thing, one of the main things they have to do is they have to learn to draw. Drawing is the lead to good painting. It’s the basics. Now, whether you learn like Da Vinci or you learn loose like you want – comics or whatever. Like Meron [SPELLING] or any of those. Learn to draw in your own style. My ballpoint pen is my best drawing tool. I can get as fine a line and shadow. Also I’d like to speak about Joe Fischer.

HG: I’d like you to, please.

WW: Joe Fischer, I met when I went to Empire State College. Joe Fischer gave me an appreciation for color. Oft times, students will learn and these TV teachers will tell you to use multiple different colors. Oh you can have a pallet as wide as this stage. Joe taught me to use twelve colors, and so I may use two reds, two yellows, and a blue, maybe two blues, and maybe augment that with the white, but I never use black, because you can develop colors with your blues and reds in the purple range that are as deep as a black. And he also taught me to respect the thing that I call triangles. A triangle, rather than the color wheel. At each end of the triangle, a red. On my right, a blue. A blue on my right, a red on my left, and a yellow at the top. And then you do the gradations between them. And across them and you can come up with whatever hues and values you want. Tinting them with the whites and sometimes you can use the sienna and the ochres to moderate them, but I learned that you don’t need to have a whole spectrum of colors. You just learn to work until you get your own sense of color. Another wild tale. When I came back from the service, I went out to UB and I didn’t succeed the first year. And the counselor told me I needed to study art, which was apparent from the test they gave me. So I went over- he also unfortunately told me I wouldn’t qualify for UB, well, I’m [unintelligible]. And so later on I found out that Empire State gave you a degree for learned life experience, and I had learned life experiences, and so I went there, but I majored in art and studied under Joe Fischer. Now he was teaching photography and color, but he taught me how to study colors and along with it, I can make a color that you can hardly see when you put it against other colors that I had put on the page. So, I learned how to pick green by red and how to pick the blues by the oranges, so there’s a lot of things you can do without following the rules.

HG: Will you talk a little bit about your relationship with Joe Orphio?

WW: Well, Joe and I have been friends for I’d say about twenty, thirty years. Oft times I’d see him at a show and Joe would come up, hug me, “How ya doing, Bill?” And I didn’t pay much attention till about couple of months ago Joe introduced me to a thing called Skype. And Joe talks to me about two or three times a week. And he is a consummate painter. He tries to do a painting a day. We don’t paint the same way, we don’t see life the same way, but Joe is a consummate painter. He’s a true friend. He’s like those other fellows that I was telling you about in the story. Joe is down to earth.

HG: Now did you know him when you were at the Art Institute?

WW: No. I did not. I met Joe sort of through the various shows. We would go to (unrecognized word) show or Catherine (unrecognized last name) show, or Bob Blair’s show. And I hadn’t paid much attention to his work because he was coming through it, but since I have been talking to him on Skype, I found out that he was at the Institute before the war. He was cleaning up around there and into his sense of art. And in there again is do your own thing. Joe works in what one would call an abstract medium, but I’ve seen some of his work lately that is brilliant in color. Joe’s quite an artist.

HG: He really is.

WW: Yeah. And he has a few artists in his family. I think he told me this one fellow who he communicates with over in Holland found his CEPA, Joe’s real people.

HG: Thank you for taking part in the Living Legacy Project at the Burchfield Penney Art Center.