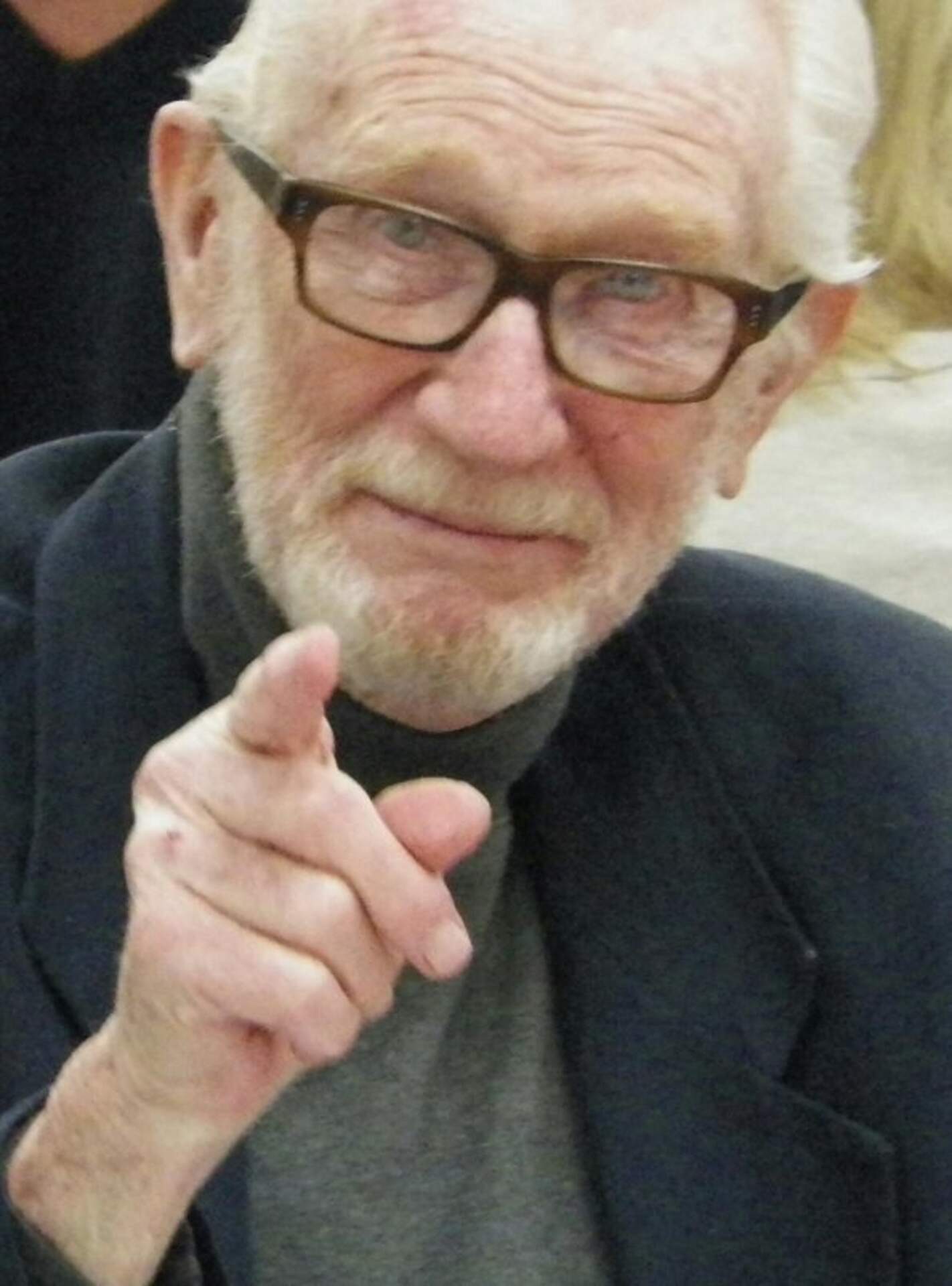

Joseph A. Whalen

(1927-2015)

American

Born: Lockport, NY, USA

Joseph Whalen is part of the Living Legacy Project at the Burchfield Penney Art Center. Read the transcription of his artist interview below.

Joseph Whalen is a painter and educator born and based in Lockport, N.Y. He works primarily in watercolors and acrylics, often painting barroom scenes, landscapes, and portraits.

As a young boy, Whalen spent three years in the hospital with a bone disease. He began drawing during this time to pass the hours. He started painting between the ages of 16 and 20 and then went to Rochester Institute of Technology to study art. After completing his degree at RIT, Whalen studied at the Albright Art School, the University of Buffalo, Niagara University, and Buffalo State College. Over the course of his education, he credits teachers Sister Mary Julia, S.S.M.N., Marion Hazen, and Ralph Avery as particular inspirations.

Whalen taught art at North Park Junior High in Lockport for 33 years. He founded the Niagara Frontier Watercolor Society, became a member of the Buffalo Society of Artists, and is president of the Market Street Art Center in Lockport. He has given private lessons at his summer studio in Olcott Beach and spent four summers in the medical illustration department at Roswell Park Hospital and three summers in the technical illustration department of the Cornell Lab.

Whalen’s paintings and drawings, taken as a whole, constitute a chronicle of life in Lockport over more than a half-century. He has exhibited his work at such venues as the Burchfield Penney Art Center and the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo and the Kenan Center in Lockport, and he has won a Gold Medal from the BSA.

He and his wife of over fifty years, Kathleen, have 8 children, 26 grandchildren, and 2 great-grandchildren.

In 2013 Whalen was designated a "Living Legacy" by the Burchfield Penney.

Transcription of Joe Whalen's the Living Legacy Project interview:

Transcriber: Courtney Rowley

Date recorded: 8/25/2014

HG: This is the Living Legacy Project at the Burchfield Penney Art Center on August 25, 2014 and I am here with Joe Whalen at his house in Lockport, NY. And Joe, thank you so much for being a part of the Living Legacy Project.

JW: I’m honored. Thrilled, especially since I’m at that stage in my life where I’m starting to turn into dust.

HG: Well I don’t want to hear that yet.

JW: No, no we won’t talk about that.

HG: This is about life and living.

JW: Absolutely. I’m trying to do that.

HG: Thank you so much for agreeing to meet with me today and participating.

JW: My pleasure.

HG: Joe, we were kind of talking about this earlier, but can you tell me about what inspired you to want to be an artist?

JW: I’d have to go back to when I was a child, at 7 or 8 years of age I was quite sick. A bit of a sad story, but I had a very serious bone disease and I wasn’t expected to pull through it. I started to draw then, in the hospital. Up to that point, I didn’t pay too much attention, it seemed to me that I enjoyed drawing more than I did anything else. I continued to do that and they sent me to a sanatorium for 2.5 years and I drew a lot there. I used to have a fellow that came in and gave us craft lessons, I remember I enjoyed that and I used charcoal and pastels which I had never used before in my life. This thing just grew. By the time I got better, I was sent back to school, the parochial school. When I was in 7th grade—no, 6th grade I decided to take lessons in drawing and painting from Sister Mary Julia, who was a Belgian nun who taught art at the convent. So I went there with her for a number of years and she was marvelous, soft-spoken, loved art. When she said conte crayon, I just loved to hear her say it. It was mostly pastels, I didn’t do any oils, mostly pastels, soft pastels. She bought them, of course that was the beginning, I was all enthused. Then I went on to high school, I had two great instructors: John Cole, 9th grade, and then Marion Hayes was my senior year instructor, she was marvelous. She was continually encouraging me, she was a great inspiration to me. So of course from then on in, I wanted to go to art school, which my parents couldn’t necessarily afford it. So I applied for state aid for disability. Even though I was not considered disabled in my mind, I was in the eyes of the state because it’s an incurable disease. I got a scholarship to Rochester Institute of Technology—RIT, I got a full scholarship there.

HG: Oh my god that’s incredible.

JW: It was, it was great. When I was there, there were two others in the same boat, (??) and another guy, we were all disabled but having a good time. Of course RIT is where I loved myself, I loved drawing, I loved painting, I loved the instructors, and there were some great ones. Ralph Avery was probably one of the greatest watercolors I’ve ever met, and Aileen Clemenson, and people like that. Clifford Al(?), and these guys were contemporaries of many fine painters and the GRUPPE, I’m trying to think of some of the others. That whole group of painters that were down on Cape Cod, the New England part of Cape Cod, that whole group we were part of. We all learned things, I learned from them, oh they were great. That was a great school and then I had a spiritual problem. Thought maybe I wasn’t worthy of what was going on, so I went to seminary for 3 years. And fortunately for the church, I gave that up. But I painted while I was in there too. Then when I came back I went to Buff State, and the Albright Art School was still going and I went there too. Mr. Elliot was a great teacher, I thought. I took a painting class and an art appreciation and I don’t think I took a better art appreciation class in my life. We used to meet in the auditorium of the old gallery, the Albright Knox gallery before it became the Knox. He was a kind person, he wasn’t full of himself. Many artists and art teachers are so full of themselves. You know, questioning the slightest bit of reasoning. And his wife, [Virginia Cuthbert] I took a class from her, and I took a printing class. A good staff in terms of reputation. I took a photography class which I didn’t want to take, but I still took it, from –oh you’ll have to look it up. He ended up being the head of the photography department for the Museum of Modern Art, he just retired, he may have died. He’s quite famous. I wasn’t a very good student.

HG: But did you enjoy the class?

JW: No. No, I didn’t. I should have but I didn’t. It was a foreign thing for me, photography.

HG: Why’s that?

JW: I don’t know. I wasn’t interested in that type of thing. I liked the results of photography, Cartier—we saw all those photographers. But I didn’t care for all the southern assets. Which I call nonsense. But I got through it. What was his name? You’ll have to look it up, well known in Buffalo, he was one of the biggest names to come out of that area, and he ran a photography department, and he retired. He did some quite beautiful work, he didn’t need me.

HG: Can you tell me a little bit about the Albright Art School itself?

JW: Well, I enjoyed that but I enjoyed some of the classes at Buff State just as well. Painting classes there I didn’t fully appreciate because I wasn’t an abstractionist, but I was involved it in it. They were teaching that type of thing. And I enjoyed my academics at Buff State too.

HG: What years did you go to Buff State College?

JW: I knew you were going to ask me that. I went there the summer of 1949 and 50, taking summer classes. Because I thought if I didn’t make it as an artist I could be a teacher, and I’m sad I gave up already. And then I went a couple years in a seminary. I went back to Buff State in 1953 I think, I must have graduated—you’ll have to look it up because I went there off and on. It took me longer to get a bachelor’s degree than it takes most people to get 5 degrees.

HG: Why was that?

JW: I don’t know, I just couldn’t make up my mind what I wanted to do. I went and did graduate work there, Buffalo State, Niagara University, and the University at Buffalo, all three of them had the pleasure of my appearance. I didn’t finish my masters, I did finish the hours but I never finished my thesis.

HG: What were you going towards your masters in? Education?

JW: Art Education.

HG: Because that’s one of the most, that is what many artists do. I wanted to ask you, did you go to Buffalo State around the same time as Victor Shanchuck.

JW: No, but I know Victor. I may have but I didn’t know him then, I know him now of course. I’m trying to think of who was there, I worked nights at Bell Aircraft when I was at Buffalo State.

HG: Then what did you do when you were finally done with school in whatever capacity?

JW: I was taking a summer school class with a group of teachers, graduate class, and they were from a certain community—Barker. I impressed them, how I don’t know, but there was an opening there and they just thought that I should be the one to take it. Well, I had to get a job, so I went down to Barker. It was a combination job, teaching Art and running a Boy’s home. Don’t ask me how I got into that, but I did. I did that for three years that was an experience. I lived right with them, they didn’t worry too much about whether I taught art or not, but they were worried about whether or not I took care of the boys. These were kids from all over the country having problems, I wasn’t equipped for that. I wasn’t equipped for that, I don’t know what they thought I could y’know, but I did and it was a good experience. And then I met my wife on a blind date and we got married and I had to quit that job. I left there and I came back home and went to Buff State and finished up whatever remnants of a degree I had going. And then I taught Lockport. Oh no, I’m sorry, my first teaching job was Niagara Falls 54, 60, somewhere in there.

HG: Wow, so early 60s. How long were you an art education teacher?

JW: 33 years. Barker, Niagara Falls, Lockport and I retired from Lockport.

HG: So I find people who teach art at the same time as producing their own art, sometimes have like maybe a different relationship with their work. Some of them, it makes them more impassioned and other times they find it draining. What was your experience as you were creating in your own right as well as teaching it? (10:29)

JW: Because teaching Art for me wasn’t a high pressure job, I had time to paint not on the job, although I did do that occasionally. I could paint at night, and I painted a lot then. And then summertime came along, and I worked at Roswell Park as a medical illustrator for 3 years, summers. I’d get a grant, and that took me to another entire new area, which I enjoyed. And another year I worked at Cornell lab as a technical illustrator, which was terrible. It was all straight lines, charts and graphs. Teaching helped me paint because it gave me time. I liked teaching junior high, I made a lot of friends, they were mostly students. I got a letter just the other day from one in NYC, so I still have a lot of contact with these students. Jay was just with (??) another former student of mine, who has a collection, how many pieces does he have?

Other voice: Well over a hundred.

JW: Just a guy who is collecting.

HG: I’ll tell you, I am having a similar experience now that I’m managing interns and work study students at the museum, and most of them are around 5 years younger than me tops, although some are 20 years older than me depending on where they come from. And at a certain point you stop viewing them as people you’re supervising and start viewing them as friends. It’s a really beautiful transition when that sets in.

JW: Well I have a lot of them, I just had a visit from someone from Washington, they had paintings of mine, a number in California, I did a lot of work here in Lockport, a lot of work. I painted a lot of things in Lockport. A lot of Lockport scenes, probably close to 200 houses, paintings.

HG: All in Lockport?

JW: Yeah. Churches, that’s how I made a living. Well, I did make a living, extra living. But I had an interest in Bar Room environments, to me they’re like opera. Of course I was involved and I painted a lot of bar room scenes and I had a lot of people collecting them. That was a big part. I envisioned myself as John Sloane or somebody. But I enjoyed doing them, and I did a lot of them from memory, as sketches, no photographs, no nothing. All from in my mind and memories of where I was and where I had seen the environment, I have a lot of those.

HG: You mentioned a lot of the commission works you would do of Lockport scenes and bar room scenes, what are some other themes that have emerged in your work over the decades?

JW: Well, as I said, I did a lot of houses, people like their houses, paintings of their houses. I’ve done a few second rate murals, a few. I’m not gonna tell you where they are because I’m hoping they’ve been painted over. People seem to think you can do everything if you’re a painter and I had the reputation in Lockport of being an artist which is a little extreme too. I think the bar room paintings were the most intense, and the most important to me. Because they weren’t just bar rooms, they were things that happened. Pool rooms too, like that little pool room, can you see it? I worked in a pool room for a couple years when I was in college, that was one of my other jobs. And I was a pretty good pool player, not the best, but pretty good. I enjoyed and I remember the people that came in, people was what I was trying to paint I guess. To this day I still do the same thing, I don’t know how to explain that to you, exactly. I had a lady call me this morning to tell me she just bought a painting. It was actually a small one, I had forgotten all about it. It dealt with three biblical ladies, I gave her a fictitious name, Betty, there’s no one in the Bible called Betty. I did that so she could attract attention, I did these three, what were they doing? Anyways, she called me from Ithaca to say she bought it today, and I had almost forgot about it.

HG: Where did she buy it from, was it a gallery?

JW: The gallery there, yeah. Things like that. I have a good friend, and she’s a good painter, a fine painter, she has one of mine that I enjoy so much. It was Christ having breakfast with Lazarus because they were good friends. All you ever hear about is him raising Lazarus up and all that death scene, so I figured if they were good friends they must have had breakfast once in a while.

HG: So that’s interesting, so it seems like there must have been a lot of religious themes.

JW: Yeah, I did a lot. Interpretations of religious scenes in real life. Often times, what we a view of with religious scenes they’re clouded with heaven itself, you know. And they should be for inspiration. But I did a lot of, many of my religious themes were pretty ordinary circumstances. Very ordinary people. I’m trying to think of something that I can’t think of offhand right now. I’ve probably done 6,000-7,000 pages in my lifetime.

HG: That is quite a prolific career.

JW: It’s just hard for me to try to recall so many of them. A lot of drawings, I love to draw. I don’t want to tell you about the religious works because I’m not sure people would fully understand what I’m trying to say. I did a number of them, is that terrible? Christ as a human being not so much as a divine person, that type of thing. But who I think of would go haywire on that.

And, what else? I had a lot of shows, one champion of mine was out in Chicago, a doctor, he has about 65 paintings, and a psychiatrist in Pittsburg, he must have 10 to 12. People like that, and another guy in New Jersey.

HG: Well your pieces are very, both visually stimulating and intellectually. A lot of the time your titles are very tongue-in-cheek, it kind of hints to a deeper point you’re trying to make.

JW: Absolutely. You understand why, I’m not just trying to be funny. Contemporary art, which I’m not against, some of it I like some of it I don’t like, will do a painting and it will say “no title/untitled.” Well, that’s a terrible thing. What are people supposed to look at and associate, project, if there’s nothing there to lead them? Now my work has realism, so it was easier, they can follow it, but if it was a totally abstract subject and I had no title on it, it’s an abstract object. I disagree with those painters that do that. I don’t think anyone should ever do it because the whole purpose of painting is what? Sharing. If it isn’t sharing then what’s the sense in it? You can sit in the third floor of the house and say I’m the greatest painter ever who ever lived and never show anybody anything. You could do that I guess, but it’s not true. Even Cezanne felt the same way, unless you could share something with someone, it had no point. I’ll admit some of it is pretty amateurish, not very clever, not very talented. Maybe, I don’t know. But anyone who wants to pay for it, as long as they don’t use numbers and trace photographs, they’re fine with me. Any of it could be art, but no numbers and no tracing of photographs. I don’t like photorealism. The reason I don’t like it, I have questions in my mind right away. I don’t believe them. I could be a cynic but I don’t think..

HG: Well the camera obscura has existed for hundreds of years.

JW: Oh yeah, I’m not against photography. Well, you’re right. (Indecipherable) He did the light so well way before cameras, Caravaggio was good, very good, but other than him not as big a name. But then you’ve got Vermeer, Vermeer is of course.

HG: Well pre photo, but it is high realism. I would love it if you would please talk about your creative process.

JW: I could give you an example of, I can’t give you a concrete example of what it is, but I haven’t been able to paint now for 6 months. It’s like a hole in my life. I can’t find a comfortable view of anything because I can’t paint. A lot of it is because I’m weak, I can’t stand, it could be all that. But not being able to paint, not being able to produce, I painted every day for 50 years, 60 years, I painted every day for at least 50 years. And this has been terrible, I can’t relax because I can’t paint I guess. I don’t know what the creative process is, but it’s just more than just ability. It’s more than that, I hesitate to use the word “talent.” The reason I hesitate to use it is because it’s so misused. Every kid who picks up a guitar, within a week he’s got talent, or a ball player who can catch a baseball, oh big deal. Why is that talent? Especially why I’m doing this. My story. In junior high I was in science class, and the girl next to me had the same last initial so she sat next to me, she was the brightest kid in the whole school. She was a nice girl, quiet girl. Anyway, we had to draw our experiments, beakers and things, you know, as well as you could. That was part of the science. And of course I overdid it, like they were going to be paintings, she had a hell of a time. Oh god, and she says “how can YOU do it so easily and I can’t do it at all?” I said “ I don’t know. I can’t answer that question. I don’t know why I’m capable of doing this. If you want, I’ll help you do yours.” And I don’t know the answer, I don’t know why I can draw, but my mother can’t, I have no idea. There’s no question about it. Over the years, it’s the first guy, you know that French guy in the caves? Whatever they are, those drawings on the wall? The rest of the people must have been like this: “where the hell did he learn how to do that?” and he didn’t know! I don’t know, it’s hard to say what prompts the creative spirit. Many of them are so confused, like van Gogh, he’s the best example, the most popular example I can give you, there are others. But with van Gogh, what confused him, his work was so automatic, so intuitive, so beautiful and so colorful. He didn’t understand it I don’t think. Whether or not he killed himself, I don’t know. I was never sure of that, I say he did but… I don’t know how to answer that.

HG: You answered it wonderfully.

JW: The creative process. He’s got it and you’ve got it too, in different ways, maybe.

HG: And that student had it in different ways as well, she might have… Creativity isn’t just art, you know what I mean? That’s something that we learn more and more. I was talking to a friend the other day who is in his mid 50s, he’s really involved in the maker movement in Buffalo, which is people who make their own electronics or make their own different things and he’s really good with computer coding and he’s really good with welding together circuit boards and everything, and he’s like “that’s my art, that’s my creativity.’

JW: He does it with ease, and relief, and satisfaction. You have all those there. I want to give an example of confusion of creative purpose or the whole idea, I talked to Jay about this, I had a kid in class, a nice boy, quiet, and not very bright in terms of school work. Matter of fact, he never finished school. I had him in 9th grade, and he quit, it was hard work and he just couldn’t, he was such a nice kid. Anyway, years later, he called me up and wanted to buy a painting of mine, he saw it and wanted it. He’s working a menial job. He lives in a room in his sister’s house. I said I still had that painting, but it was kind of expensive. He says ‘I’ve been saving my money. So I had enough that I could call you.’ I said “My god, what an honor.’ So he came over, he had $600, I gave him the painting for 100 bucks. I had to take something from him, I didn’t want him to think.. I thought to myself ‘what a lucky son of a gun I am.’ I didn’t think it was a great painting. It was alright, it was skillful. But he was thrilled with it. And something in him wanted to buy that painting. I don’t know, I have a couple stories, but nothing as penetrating as that. That’s why when I run across boastful, pig-headed, braggy artists I get upset. I don’t like them, I’m not supposed to not like them, but I don’t.

HG: You are, you’re supposed to have your own opinions.

JW: But there’s one thing you have to have if you want to be a painter and continue to paint and then improve. There’s one thing you have to have and that’s humility. I mean, you know yourself. Not you people saying, oh he’s such a nice guy. (Indecipherable) I don’t know but, I can’t say to myself honestly, nah that’s okay but it’s not exactly what you want. It’s alright but it’s not EXACTLY, you didn’t really get it. And then you can continue from there. Am I making myself clear?

HG: Yes you are, know thyself, right?

JW: Yeah, that’s where I think Burchfield was great. Well I first got to know his work in High School, and that was when Marion Hayes was my teacher, she liked him. And he was living in Buffalo at that time, and he was a big name. But I loved his work. I never really got to meet him until a lot of years later. But I know his daughters fairly well.

HG: Really? Which ones?

JW: Catherine Parker. Martha Ricker and I were not close friends but we knew each other. We drank a little, not a lot. But I liked her, we talked a lot, maybe 5 occasions. We were on a TV show years ago when channel 17 was public television. The two of us were on an interview, I forget who interviewed us, I remember it was (indecipherable) I don’t why I was there, but I was. And she never seemed to paint (indecipherable) but I like her work. I think she taught for a while at the Art Institute and I had friends that went there. But where was I was I was going to talk ---

HG: About Charles Burchfield. Yeah his honesty. Willingness to expose himself. Boy that takes a lot of guts. I tell student painters, I say what it takes is a lot of courage. You can’t be afraid not to paint this and show it to someone. Sit in the living room and put it in a frame, and put it on the walls, show it around and get it into a show or something, DO something with it! Get some peoples’ reaction to it. And you’ll find out whether it’s a painting or not. And you can take that, you gotta be able to take a little criticism. You know that’s so important. Peter Busa, you remember him? He taught painting at Buff State. Actually I always said, “Peter, you must have been undermarked (indecipherable.) “ “No, I don’t.” As far as I was concerned he didn’t like painting at all. He was angry, he was an abstract painter. I wouldn’t relent, I would change, but I wouldn’t relent entirely.

HG: But I think in some ways you and Burchfield have some similarities. You do a lot of figurative portraiture and Burchfield really stayed away from most figures.

JW: His figures weren’t very good, were they? Oh, no.

HG: But I think what’s interesting is that in Burchfield’s work you can see kind of how he’s, I don’t even know if he was intentionally playing with abstraction, but he was playing with these more expressive ways of representing what was really there.

JW: He was trying to paint the sounds birds make. He was trying to paint the sounds that crickets make. No one has ever done it since. And that’s exactly what he did.

HG: And in your works too, I can see this more expressive quality of moving away from how someone actually looked to trying to convey the energy inside that form. And I think that’s a really nice sort of overlap.

JW: It’s a hard thing to do without distorting. You see that little silver painting, you see that one? (The top one?) Yeah, motel room. I try to show, I think when you’re young you think “oh my god, I got a job, I’ll travel and live in motels.” It’s not all it’s hyped up to be. I found out with this fellow there. You end up most of the night sitting at the edge of the bed watching foolish TV.

HG: Thank you so much for talking about your thoughts on Burchfield. I’m just happy that we’re doing this interview, you know, because I’ve been calling for about a year now. Being like “How’re you feeling?” Especially as I’m hearing you talk now, I’m so grateful you’re taking the time to talk to me, you know. You have some really great perspectives and you’re not afraid to share them and that’s what makes a good interview.

JW: I’ve got a big mouth.

HG: You’ve got a big mouth, this is what I’ve heard. I told people I was coming here today and they said “good luck with that.” And I said “thanks, I’ll have a great time!”

JW: Yeah, big mouth. Nancy didn’t say that did she?

HG: No, she didn’t.

JW: I like her.

HG: Oh no, she’s wonderful. And everyone said they liked you.

JW: No, no, I know what they meant. Yeah, yeah, (indecipherable) even commented on that one time when I was up there last year, two years ago, they had a little thing for them.

HG: For the Artists Among Us, right? You had a piece in it and it was one of my favorites in the show. I can’t remember the title of it, but I think it was the title that really cracked me up.

JW: Was that the watercolor of the guy coming home? It wasn’t ready.

HG: I think so. It was the guy with longer hair, straight hair. It was an African American person, or something like that.

JW: Almost African American. (Darker skin tone.) That’s the one.

HG: What’s the title of the piece?

JW: It was one of those long titles, after working all day long in the forest and I came home and my supper isn’t ready. That type of thing. And she was very sad, and she was a nice girl. And she was very white. Yeah, very pale. There was nothing meant there either.

HG: And that’s interesting too. What are your thoughts on what people might read into your work that you didn’t necessarily intend to include there. Like opposite of abstraction having no commentary.

JW: Well, I haven’t had too much of that. Most of the people I deal with are probably afraid to say something. I don’t know, I haven’t had to, I love talking to people about my paintings. Especially to those that buy them, and I try to convince them that they did the right thing. That pool player’s as abstract as I can get. That it is abstract, it is, wish I had done it larger. I used to teach kids at school, the first thing you have to do is shape, and every one of you knows shape. If you don’t know shape, you must have skipped kindergarten. You know that a pear look like that, an apple is round a banana is this way. Everyone knows shape, I said ‘what’s an artist do? He gives it form by showing where it folds over or bends over, backs up, whatever it does.’ That’s what the artist does, now he has to learn how to do that with some skill. “I aint gonna be no artist Mr. Whalen.” I said, “no, I know that.” (laughs) I shouldn’t say things like that, the poor kids.

HG: Sometimes I think they respect you more when you’re stern with them. Because they’re trying to mess with you.

JW: Well I used to have, I used a textbook “Art Today” which is a hell of a textbook. You can use it in college, you can be used in high school. But in it are a lot of illustrations, there are some nudes. So with my 9th graders, the day I pass it out I said “Now, everybody, just open up the front page. Now here look up on page 33, that’s a bare naked person. Now if that bothers you don’t look at it. Turn it over, you don’t have to look. But don’t touch it up! It doesn’t need any additions.” I’d go through about 20 pages like that. Consequently, nobody ever touched up that book.

HG: Good, well done!

JW: I wouldn’t suggest that as a way to do it, probably’d get fired if I did it today.

HG: You’ve had a very successful art career independently of being an art education teacher, can you talk a little bit about what you had to do over the years to build your career as an artist in WNY and beyond?

JW: Well, let me see. Of course being a member of the Buffalo Society and a few other groups helps get your work out of Lockport, other people see it from out of town. And one thing leads to another, and the more you sell, the more you make it known. I think that’s part of it. But I’ve been involved with the art movement in the Buffalo area as well as I could over the years. I’ve been in the Buffalo Society for well over 50 years. I was an initial member, beginning member, founder of the Watercolor Society. Things like that. It builds your name. It’s kind of hard to say, my career in Lockport rose well because I sold a lot of paintings and people still liked them and me apparently.

HG: You did a lot of commissioned works too?

JW: Oh yes, a lot. And I don’t like those. (indecipherable) I did a very nice house, and she wanted it (indecipherable) and I went across the street, so she couldn’t see me, so I could sketch the house. And I thought I made a very nice sketch. And I did the painting and thought “that’s not a bad painting, but it’s a house.” It was a semi-modern little French tudor. And I brought it to her. And she liked it but she said “you forgot the lilac bushes.” Well, I had a couple martinis in me. And then I said “that makes the painting a failure, so you don’t have to have it. What I want you to do, I’ll take the painting back, you call, I can tell you 2-3 high school students who can do the job better than I could do it.” I shouldn’t have done that. I walked out. “You forgot the lilac bushes. God damn it,” I thought to myself. “You jerk. She had more lilac bushes than tulips.”

HG: I love that because I have friends that are artists, that’s something that they often run into, just because someone hires you to create something, then they think they have complete say in what you do. You just might as well be a camera. And now you have people that just want the filters on their camera that make it look like brushstrokes or something like that. And if that’s what they want, give them that, but if you want something by an artist you have to step back.

JW: In 1953 or 4, I had a friend of mine who was a photographer, a very close friend in Buffalo. Had a studio on Elmwood Avenue. I went to RIT with him, terrific guy. Just, I love him. His name was Kevin (indecipherable.) He had a friend that was in Germany, who was taking photos or even sketches and then painting them and then taking photos of them so they looked like they were painted. He wanted me to get involved with him. I didn’t want any part of that. (Indecipherable) Nothing like that meant any harm. That guy in Germany was the biggest whore right at the moment, I thought. That’s what he was doing. Taking photographs and then painting over them in oil, passing them off as oil portraits. Well I had to deal with a hotel chain once, I can’t tell you what chain it was. Lowe’s I think it was, to make paintings for their rooms, motel rooms. And they sent me a list. 5 farm scenes, 2 snow scenes, a whole list. I couldn’t do it. Not that I’m not capable of painting snow scenes, I just couldn’t do it.

HG: Would it have been different if you had had 5 farm paintings sitting around already done?

JW: It might have, yeah. I might not have been as bad as I thought I was.

HG: Oh no, no no. I’m saying more like it’s the way you think about something affects your ability to do it.

JW: There’s no question about that.

HG: We talked earlier about some themes in your art. We talked about religious subject matter, and bar room scenes, and treating religious subject matter as you would experience it in an everyday setting, as you would live it. How do you deal with thoughts of these two different worlds of bar room scenes and your religious views? Where’s the link there, is there a link?

JW: I wish I could show you a painting, it was a big one too. The old testament prophet, it was Isaiah, you’re right. He didn’t want any part of it, God said you’ve got to go and straighten everybody out, and he went “not me,” yes you, you’re the one who’s got to do it. He didn’t want to do it. So I have this bar room scene four or five different people, a girl bending over craning the men, a couple of guys and a bartender. And here’s Isaiah at the corner with his hand raised up, trying to convert and change and tell these people what they’re supposed to do. You can see it was painful. I love that painting. Today you’d have to go to a bar room and repent, that was one. Christ and Lazarus having breakfast, I enjoyed that.

HG: When you’re painting bar room scenes, you’re not necessarily looking on it as seedy.

JW: Oh no, no. Every character has deep character. Oh sure. And they have nicknames. Oh god, Gravy Conley, trying to think of some, Paul Bundler (?), Railroad (?) and Ernie. All these guys were people that I painted.

HG: And they were real people?

JW: Sure! Crazy names but real people. Yeah. Sailor Burke, I did him and had 20 people want to buy it. A girl bought it, young girl. It was at a show. I did say Sailor Burke, didn’t I? They wanted to know who it was. These were hard drinkers, many of them alcoholics. Of course I became an alcoholic myself, because I wasn’t able to handle it. I haven’t had a drink in 20 something years, but then I was not so good. I thought I should be part of it. I did a painting of a lady, she had a white glove on and a hat and a dress, fairly nice dress. She’s got a glass of wine, at the Niagara Hotel, which is not the greatest place to be. And that painting, I wish I never sold it. I’ll tell you a story, now I don’t know how I could ever prove this, but the painting used to hang at the Field Stone Inn. I used to hang out there, I did a lot of paintings for Lou. One night I was out there, was late, it would have been closed, and there were two guys and a very well dressed woman. They were still there, drinking at the bar. They had enough. She mentioned to Lou about the painting, she came down, she was [indecipherable’s] sister, and she wanted me to buy the painting back from him and I said “I can’t do that.” She said “I’ll give you the money,” I said “no, I can’t do that. If we won’t sell it to you, I am not going to buy it back.” She had the ugliest mink coat on that I’d ever seen, there weren’t that many minks in the world to make a coat that big.

HG: Did she want it?

JW: She wanted it. I’ll never forget the night because one of her, she had two boyfriends or whatever they were, they were good people. It was the first time I remember seeing a guy with a cigarette case offer her a cigarette, talk about was he ever a phony. A silver cigarette case, you don’t see that anymore. Now that story is mine, whether we could prove it or not, I don’t know, she’s dead now. I knew a black bartender that used to bartend at Chez Ami on Delaware Avenue, it was the famous night club in Buffalo, Chez Ami. He knew her well. And it had a revolving bar, and he said she could, by the time it got to the other side of the bar, she bought everybody in the place a drink. She must have been a very nice person. Now I can’t prove that story.

HG: It’s a good story to hear.

JW: I like that painting.

HG: It seems like a lot of your subject matter, the way you treat your subject matter is deeply personal things that you’ve experienced and also in this very humanizing way. And it is true that religious subject matter is not accessible. It’s viewed as something that you idolize, rather than something you would think “how would I relate in these situations?” And also on the other side of it, humanizing people who might be viewed of as not worth the time to get to know in that depth, you know, like in bar room scenes and all of that.

JW: You know Thomas [Hart Benton’s]’s painting of—is it Sarah taking a bath and old men are looking at her through the trees. Is it Sarah? Something like that, I’ve always loved that painting. I’ve always tried to do it my way, I’ve done it close a couple of times. There’s a woman in Washington who has a painting of mine, called “The Peeping Tom.” I don’t know what I was thinking when I painted it, but she loved it. She bought that object of mine, she feels sorry for the peeping tom, not the woman getting looked at. But Tom was (indecipherable) in that painting, and that was a biblical character. Was it Sarah, no Susanna. Well she was taking a bath, and they were sneaking a peek at her. Poor old farts.

HG: Thank you, thank you for talking to me about that a little more. I think you have some really interesting experiences as the artist in Lockport.

JW: Yeah probably.

HG: So could you talk about some of the ways in which the Lockport community has supported you over the years? Things that made you needed that maybe this community could not provide because of its size? I’m looking for whatever your recollections are but also as positive as you want to be.

JW: Well, I always feel like I have been treated with more accord than I probably should get. You know, people stop you and ask “aren’t you the artist?” and I’ll say “well, someday I’ll be an artist.” And I don’t know, I know so many people and it would be silly for me to, phony for me to tell you I’m not well known. Because I am. It’s not because I’m such a great person, it’s because of my paintings.

HG: It’s a double whammy, because of your paintings and because you probably taught half the town’s students.

JW: Yeah (laughing) that helped too. It’s been a great experience. I wouldn’t change it for anything. I wouldn’t change it for being in New York. I had a letter or phone call from a gallery in downtown, lower New York. And they had seen a couple of paintings, and they wanted me to come down and talk to them. And I had been going to New York on a teacher’s convention. So I said, maybe I will, I didn’t really want to. So I went to the gallery, and low and behold in the window was a famous contemporary sculptor, one of his pieces. That scared me right off, I turned right around and walked out.

HG: Really, you didn’t even go in?

JW: No, I didn’t belong there. They were dealing with bigger names than mine. No, I never went it. What was his name?

HG: Henry Moore?

JW: No it wasn’t a Moore, it was…

HG: Giacometti?

JW: Who? Giacometti, that’s exactly who it was. Walking man, only this was another original. I said, what the Hell, I’m not gonna make that leap. Little farm boy jumping in with the big boys, no.

HG: In some ways your perspective is very similar to Burchfield’s. Reading through his journals, Burchfield hated going to New York. He hated going and participating in the annual galas at the Met and these sorts of things. But he was well known in New York and respected too. And he was able to support his family on just art, especially through the depression, which was just crazy. It always made him feel so uptight. Those are my words, he would never say uptight, but I think he sort of recoiled from that as well.

JW: Well fortunately what was that gallery in New York that took him in?

HG: The Rehn Gallery.

JW: I sold paintings in New York. [indecipherable] I met her in Buffalo, she represented a gallery in New York, so I gave her a little nude, I said it’s the smallest nude I’ve ever painted. And I said you can have it. Anyway, four or five watercolors back there in the gallery, and I didn’t hear from them in months. I don’t want to lose those paintings. So I called the gallery. The phone rang and rang, and finally someone picked it up, I said “hello is this so and so?” he said, “I don’t know.” I said, “What do you mean, you don’t know.” He said, “I just stopped here, I heard the phone ringing and I picked it up.” “I said, you’ve got to be kidding.” He said “there doesn’t seem to be anybody here.” So I said “alright” and I didn’t know what to do. And I finally got a hold of her, I wrote her a letter, and sent all the paintings back to me in a big pile. Which can you imagine? Talk about being let down.

HG: About when was that? Give me a decade.

JW: Oh it had to be the 60s.

HG: 60s? Oh my god. That would not fly today.

JW: He said “Oh there’s no one here, so I picked up the phone.” I said “don’t help yourself to any of the paintings. You might be arrested.”

HG: So it sounds like New York was a bust for you.

JW: No, I never cared for it.

HG: Now do you have representation? Do you have a gallery that represents you?

JW: Not really, no.

HG: Have you in the past?

JW: Not major, no. Small gallery in California did for a while. He represents me more than anybody.

(off voice): You were in New England for a while.

JW: Yeah, I spent a lot of summers in New England. I painted in New England four or five summers. Rockland, in that area. Sold paintings up there too. But their paintings had to be their environment. Boats, sailors, things like that. I was in a hotel in Rockland called the Thorn Dyke. And the owner was there, I met him through my brother. He was in the corner and he goes “Hey Mr. Whalen come here,” and I went back. And his sister was there, and what was the woman that does the woodwork? Neville. What’s her first name? Very well known, very popular. Helen Nevelson? She puts together wood pieces. Very well known, very strange. She wore black lipstick, I remember that. You’ll find her in most art books. (Louise Nevelson) I talked to her for a while, nothing was really said that was important. It was nice to meet her though. I met a lot of people who were integral to the painters up there. John Marin’s housekeeper, I met her, and she wanted me to come over, and I said “I’m not going to come over and bother him.” She said “you won’t bother him.” I said “no, I can’t do it.” He lived on an island, just off of of Camden. She wanted me to come over and I said no. Jerry Farnsworth, he’s not as well known. I was always impressed by these people, because they’re great painters. But I did a lot of painting up there. I had quite a bit of success at a couple of shows.

HG: Now how would those shows get organized?

JW: My brother worked in a hotel, big hotel up there. That’s where they were, cocktail hour shows, that’s what they were called. They were a good time, if they were drunk they would buy anything. I worked one or two summers at Cape Cod, just to get the feel of it. I wasn’t as productive down there as I was in Maine.

HG: How much time did you spend in Maine?

JW: I spent three summers, about a week to two weeks. County (indecipherable) Camden, Rockland, a lot of little places. I only went to Bar Harbor once.

HG: And you did all this while raising 8 kids?

JW: Well I had to come home with some money.

HG: One of the participants of this project the first year I did it was Joe Orffeo.

JW: I heard Joe died recently.

HG: Yes he did, he died about six months after I interviewed him. He was incredible though. We started talking and he was just the warmest person, incredible person. And he would, even when I went back to grad school, I went to grad school in Vancouver, BC and he would call me on Skype sometimes. And he and Bill West would skype each other because they couldn’t go visit each other anymore. So even though they were like a town over they would talk over video chat. But Joe also managed to support his family with the barber shop that he ran. (JW:Yes he did) And it sounds like the whole place was just covered in psychedelic colors and these incredible motifs and all that sort of thing. And I’m always so amazed at the need to create, especially with a room full of kids running around. I’m sure it would be much easier not to, but you just HAVE to.

JW: And they didn’t mob me, I was downstairs and they stayed away. George Palmer is another one, he’s made a living just from painting. George is a great guy.

HG: And Joe didn’t get to focus on his art full time until later in life, when his kids were grown up and he and Linda got married and that sort of thing.

JW: Well I made more money as I got older.

HG: That is often the way it goes, it sounds like. Do you have any advice for young artists that are just emerging? Maybe young artists who have just finished their BFAs or MFAs? Or maybe not. Or high school students who are thinking about “do I want to really want to try to be an artist as a career?” Do you have any insight?

JW: Whatever they do in Art, they must be honest. Because it will drag you down. And I’m not talking about stealing. I’m not talking about cash register honest, I’m talking about the other type of honesty. That only you live with. That’s so important to have. Now you may do paintings that may not be exactly what you wanted but that’s okay. It’s just another step forward, look at it that way. And that’s part of your honesty. And you should be honest. You shouldn’t try to get anywhere in this business through something else. I’ve seen that, but it shouldn’t happen. That’s the first thing I’ll tell them. And then the second this is that you’ve got to have a lot of courage. You’ve got to have people say “what is it?” The worst comment you could have is “oh that’s interesting.” Oh god, you want to go home and break all your brushes. “Oh, that’s interesting.”

HG: It’s like when somebody says “that’s so funny” instead of laughing.

JW: Yeah.

HG: It’s not funny, they don’t think it’s interesting.

JW: No, no no. That’s just their way of cooperating with what they thought you said. That and the fact you have to be industrious. It’s not a field where you can be lazy. I don’t care what anybody says. You have to have the willingness and industry to do it A LOT. Probably the greatest problem with a lot of paintings, including me, is when they start them and right away they’re wrong, and they know it. And they’re going to continue them until they can’t stop it. Get rid of it and start all over again. Like painting tails on dogs. It’s just not going to work, get rid of the damn thing. Big deal, so you maybe lose a canvas. Paint over the canvas. But don’t continue to do the same damn thing over and over again. I’d probably make a lousy painting teacher.

HG: Well it’s interesting, what Charlie Burchfield, yeah you probably know about this, in his early years he would take these paintings that he set aside for like 20, 30 years. He would keep everything, every failed painting that he never finished, and then 20-30 years later he’d be looking at it and he’d cut pieces of it off, “I’d cut it here and then I’d extend it there.” He’d put in a new piece of paper and then seam it together and then make a new composition from this root he’d done 30 years before.

JW: I don’t know how he—you could see in the big paintings, you could see the seam. But he did it. And he wasn’t afraid to show it. And it did it because he was going to be honest about it.

HG: You see the pencil lines underneath the watercolor. I love it, we have the painting “Fireflies and Lightning” which is this very large painting of these fireflies and the oppressive woods. The way he made the fireflies was he glued little circular pieces of paper to the larger paper and then after he painted he would peel them away. But he didn’t peel all of them away. So there’s still a few where the little glued circles are still there because he didn’t want the fireflies where he originally thought he wanted fireflies and so you still see the little circular glued bits.

JW: People don’t call them a collage either. They’re a painting.

HG: Oh nobody calls them a collage, yep. That’s a painting. I’ve never heard anyone call what he does a collage.

Jay Krull: You had touched on somebody that Joe’s taught, and the community is like that. (Unsure of this sentence) And it isn’t just Joe’s painting, it’s his humor his stories, it’s his knowledge of history, his love of Lockport. The things that he’s given back to Lockport over time has really been, not only his arts purchased for showing and sharing but then people have used it for the community. To promote the art in the community, and the history of the community, and that really is his legacy here. And then the other side of it is that sometimes he’s almost expected to be that Lockport artist. He’s got so much lore to him, the Lockport artist, and that’s where you talk about the bar scenes, his characters, you know, you talk to him about people watching. It’s what he sees in people. A lot of times we talk about people watching, we like to be like the class spies, to watch people but not feel like you’re staring. And Joe brings so much of that out in his work and that’s a huge, huge part of it, as far as Joe’s celebrity in the area. It’s as much as storytelling and his knowledge of the area as it is as anything.

JW: I’ve done a fair amount, huh?

HG: You have.

JW: One day, I encountered two women, I had seen them before, they’re “WalMart women,” “WalMart Women” I call them, but they were downtown, going to the supermarket. And I don’t mean them—I never met them, I’ve just seen them. Anyway, I made a sketch in the car, and then I went home and did the painting. And I said to myself when it was done, yeah it was just a character painting nothing, it wasn’t a soulful painting. So I framed it and put it in the gallery. Well three weeks later I was sitting down there talking to Sally and we heard the door open and we heard some giggling, and we went outside, and these two women that I painted were looking at the painting and laughing their heads off. I couldn’t believe it, I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t dare go up to them.

HG: Did they seem pleased?

JW: Well they were large, major dorsal lumbar structure. And, of course, after a while you get kind of low to the ground. But they were laughing, they thought it was great. I wouldn’t talk to them, I was afraid. I didn’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings. It’s like the lady going around picking up the pop bottles. I think that little painting I did of her is one of the best ones I’ve ever done of a person.

Jay Krull: And that’s a little one. Paul has it right?

JW: Yeah.

Jay Krull: I was surprised how small it was because I had never seen it.

JW: Yeah, it was just a little thing I did, just knocked it out. She collected bottles and she walked. What was her name? She had a nice name. She doesn’t do it anymore. It’s people like that I’m glad I painted.

Jay Krull : And those 16. When we talked about doing a calendar it was 16 months, we started in September of the previous year. Each of those was picked by Joe. And purposely, at the end we have the presentation where we actually talk about each one of them. Last year, just because of different circumstances, we picked 12, we actually picked a little more and then Joe and I weeded through what we used last year. This year, what we’re doing is actually getting out images that people own and getting the stories behind them, why they bought it, how they acquired it, you know it’s important to them. It’s really neat to get it from the owner’s perspective of why that painting has particular meaning. That’s why I’m sorry we didn’t videotape Joe when we talked about those.

JW: Well, some of those are rather prosaic. But someone needs prosaics.

HG: Yup, absolutely.

JW: Not everybody should have to look at a painting and be afraid it’s going to come to life and kill ‘em.

HG: But I think so many people don’t realize art is there for them, a lot of people don’t realize how accessible art can be. I think it’s social and cultural.

JW: Well, it’s important. I’m glad you brought that up, you know my mother said that to me years ago. My mother was very tuned in, she was old school. She had a beautiful mind. She said you are approaching a time when people are going to buy original art. She said I can tell you that right now. She had paintings at our house at home, they’re all prints, repros (reproductions). Things that she wanted; she had a Sicily I was crazy about. It was in the parlor. She had her own idea, she said this is going to happen. You’re going into a period where people are going to have original artwork in their house. And it’s true, isn’t it? You can go through Lockport, and these are not wealthy people, but they have one or two original paintings. And that’s great.

HG: Yeah, and that’s so important. Especially working in a museum where you think a lot about it, studies have shown that if you don’t go to museums as a kid, you don’t go as an adult. Because you don’t feel comfortable in that space, you feel all those social pressures of how museums “are supposed to be.”

JW: You should probably stand at the door and go like that too.

HG: They’re very imposing and very intimidating. And I think that’s something museums in general, and the Burchfield as well, are constantly trying to confront and deconstruct, you know?

JW: You have a very human feeling up there. And I think putting that little entry in the beginning was the smartest idea any architect could have because that warmed everybody up. I can remember when you walked in the Albright, there’d be a couple police and there were guards in the doorway.

HG: Yep, it can be very intimidating. I like to say that if Charlie Burchfield could see the building, he’d hate it. Oh he’d hate the building.

JW: Oh he would.

HG: Because it’s all white and very sterile and so on, in many ways, but the café does humanize it in this kind of jubilant atmosphere that you could not create otherwise. It’s the most bumpin’ place for lunch on campus.

JW: Have you ever been to the Metropolitan?

HG: Yes.

JW: It’s awesome. You walk in there and you feel about this high. Then I went to the Museum of Modern Art, everything was enlarged it seemed. It kind of set me back I think. You’re right. I went to Cleveland, I’ve been to Chicago, Chicago was more my style.

HG: It’s not just the building but it’s also how the staff carries itself. I mentioned that I managed interns and work study students, which are like student employees from the college. And I ask all my interns to write a blog about their experiences toward the end of their internship and it means so much to me how they write about how they’ve never been in a museum like this where it feels like a family and it feels like there’s support and irreverence and laughter and it’s not this quiet dead space. I think that’s the most important to me, that we’re fostering a safe space that’s very open.

JW: And it’s still got museum quality to it.

HG: Oh absolutely.

[end]