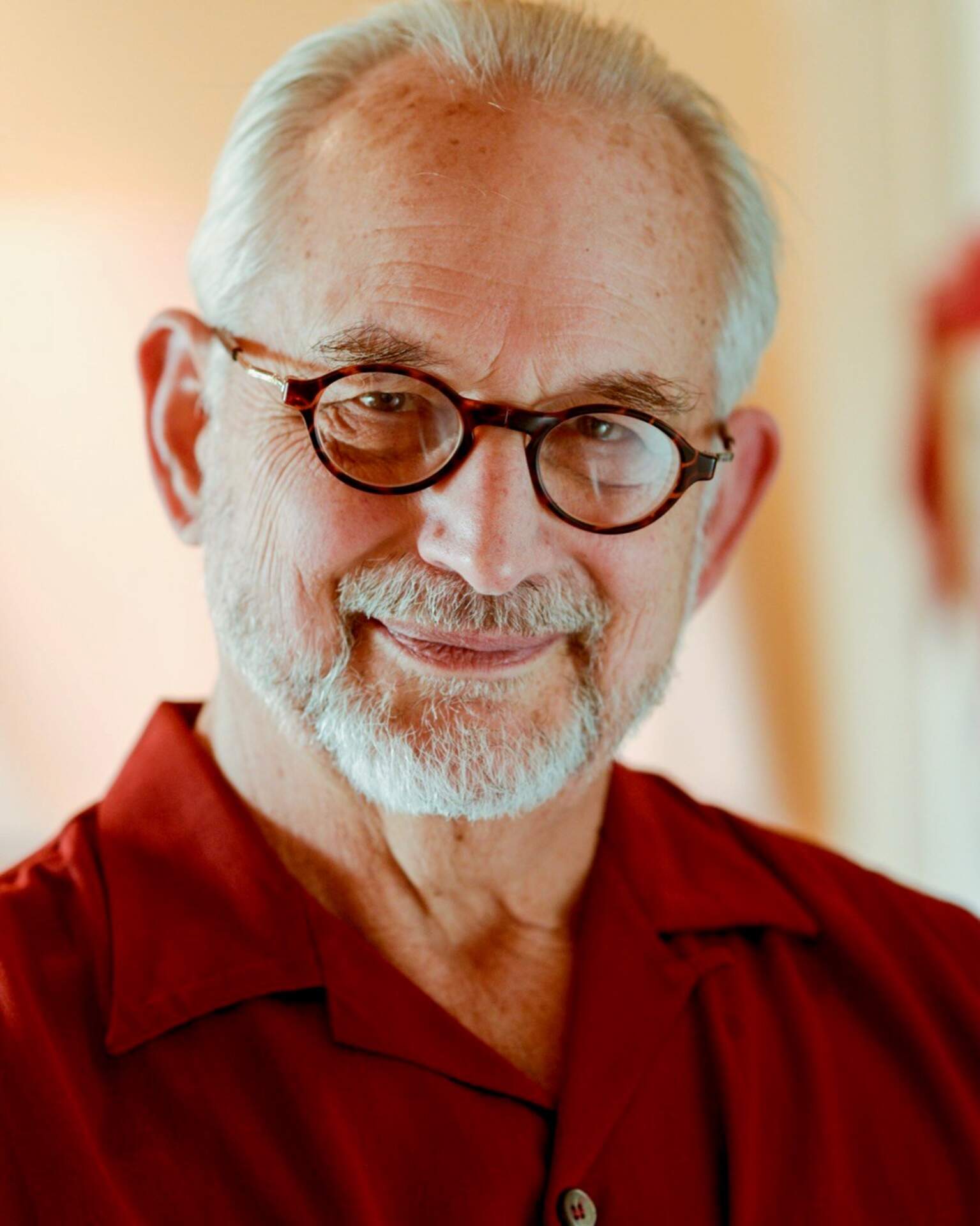

John Sacret Young

(1946-2021)

American

Born: Montclair, New Jersey, United States of America

Celebrating John Sacret Young

Many people knew John Sacret Young through his creative career as a writer, director, and producer of television and film. I knew him through another of his passions: art. We met in 2002, when he wrote that he recently acquired two works by Charles Burchfield. Sunflowers at Late Dusk (1916) cleverly captures a tall stand of sunflowers by his back porch; their colors fade as the sun sets, and a neighbor’s window glows brightly along the alley. By contrast, Winter Diamonds (1950-60) is a large, vibrant, scintillating winter scene that literally glistens with the prismatic effect of sunlight on icy snow crystals. After sending John related journal entries to quench his thirst for more information, he invited me to see the paintings, plus others, in person.

Clearly, John was a Burchfield enthusiast, so I asked him to join our national Burchfield Advisory Committee comprised of collectors, art historians, and individuals who helped us plan exhibitions, publications, and other projects. He said he would be honored to serve and was eager to visit us in Buffalo to see “all there is to see” among our “extraordinary” collection and archives. His letter from November 6, 2002, reveals how he responded to this art. He wrote:

I agree with you about Burchfield and “light” and would be glad at some point to write something or come and “pontificate” about it. People ask me how do I write—from plot, from character? My answer is I often create a scene around light. It’s fundamental to art and to movies.

For two decades we shared thoughts about Burchfield’s artwork—lively conversations on the phone, energizing emails and letters, and occasional visits on both the west and east coasts. One of the things he enjoyed about Burchfield’s winter scenes was their way of conjuring up memories of his Northeast youth. He also loved the animated way Burchfield depicted the sounds and energy of autumnal rainstorms, the heat and colors of summer, the turbulence and rebirth of spring. Each season had its unique characteristics.

John shared a poignant memory about how Burchfield’s art resonated in his relationship with people who were close to him in “The Wheelchair Tour” from his 2016 autobiography, Pieces of Glass: An Artoir. He and his mother, who was suffering from emphysema, visited the exhibition, Burchfield and Marsh: Exaggerated Visions at The Art Complex Museum in Duxbury, Massachusetts in 2004. One painting stood out. It depicts a flock of chattering goldfinches flying across a country road in a landscape filled with Black-eyed Susans, tumbling yellow leaves, wind-torn gray clouds, and gesticulating trees. John wrote:

But back before we left, I had relearned an important lesson. Holding the helm of the wheelchair helped it happen. My mother asked to circle back to a certain Burchfield work, September Road. It was sizable; say 33 inches by 45 inches, and perhaps the best painting in the exhibition. It was dated 1957, and like much of Burchfield’s work in that decade, it was swept with wind and change of season — in this case oncoming fall — and birds on the wing.

I had seen reproductions of the painting in books, knew it was energetic, and a good work, yet had let it slide by when we first passed it. I had not taken the time to see it fresh. My mother’s request allowed me to strip it free of the image I carried from pictures. This can happen, and it certainly has to me. It is tough to look at the Mona Lisa without bringing all its fame and familiarity to it. I have to shake off all the images and perceptions I might harbor. They can become baggage. I have to remember to see the painting that is actually now in front of me. Clean, as for the first time….

Back in Duxbury, I was glad my mother had asked to return to September Road. We were, it turned out, hardly ever to talk about the exhibition again, but I asked her then why she had been drawn back to the painting. She said, “I don’t like some of his paintings. They’re dark; they’re moody, a bit creepy. But this one, I don’t know, I wish it were spring, I love spring, but the fall — I can feel the way you feel in the fall — sad, but alive, like I could walk a long way again.”

…That wheelchair day remains — perhaps even more prized because she is gone now — and with it what both men [Charles Burchfield and Mark Rothko referenced earlier], and maybe the best of artists, bequeathed to my daughter and my mother, and to all of us.

A rapture.

While Burchfield was a primary focus, John’s zest for art extended to others, particularly John Marin. He wrote essays for solo exhibitions about both artists, including “John Marin: The Edge of Abstraction,” noting:

His finest work didn’t happen in a single year or in a single medium. His finest work very often is vitally stirred and rife with movement: it often includes his exploration of the frame around or within a painting that offers at once “the impression of looking through a window” and “breaking through this imagined barrier.” His finest work carries his rough-hewn lyricism and quivers of emotion; it is full of feeling. His finest work most of all finds the shoals and beauty and surprise of that territory that is real and not real and that dances movingly and elastically along the edge of abstraction.

The exhibition Land, Sea & Light: The John Sacret Young Collection shares a major selection of works that he lived with and loved. John gravitated toward artists who represent, each in their own way, fundamental light — light that permeates our lives, light that conjures memories. I miss his unique observations in our exchange of ideas about art, music, literature, and film. He enriched my life. I hope that by sharing art that inspired him, others may discover art that speaks to them too.

Nancy Weekly

Burchfield Scholar, Head of Collections, and Charles Cary Rumsey Curator

Burchfield Penney Art Center