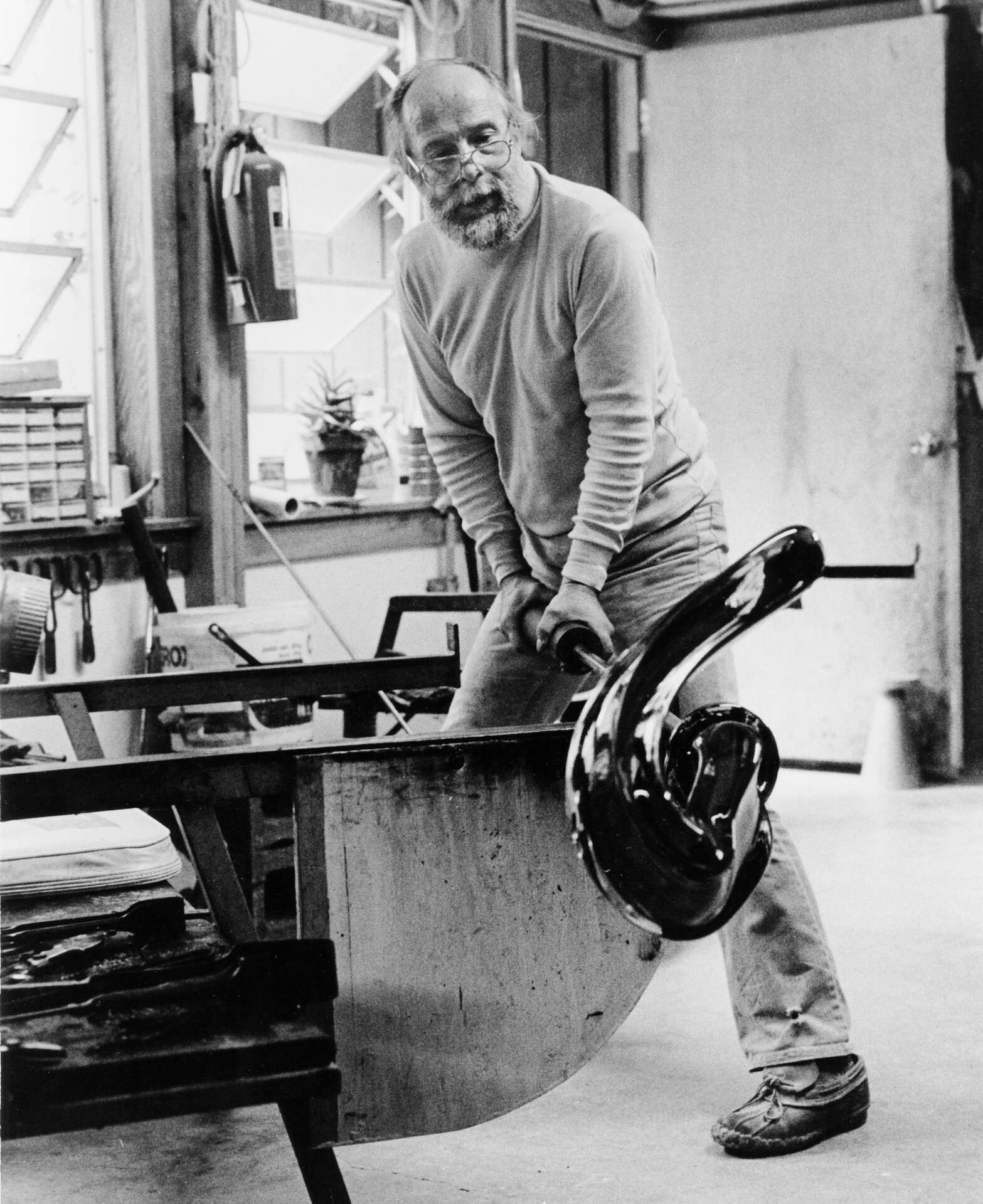

Harvey K. Littleton

(1922–2013)

Born: Corning, New York, United States

Harvey K. Littleton was a prominent glass artist born in June of 1922, in Corning, N.Y. Considered the father of the studio glass movement in the United States, he launched the studio glass movement in 1962 with a workshop in Toledo, Ohio, introducing the idea that the artist could mix, blow, and work glass in the studio.

Littleton expressed an early interest in art — and in the possibilities of glass art — but his father urged him to study physics when he entered the University of Michigan. He did so for two years, then was drafted in World War II. After serving with the U.S. Signal Corps during the war, he studied industrial design at the University of Michigan, earning a B.D. degree in 1947. In 1951 he received an M.A. degree from the Cranbrook Academy of Art. That year he accepted a teaching position in the Department of Art and Art Education at the University of Wisconsin, remaining on the faculty until 1977. His initial specialty was ceramics, but by the late 1950s he was exploring the possibility of creating studio glass. Beginning in the late 1950s, Littleton scoured the world to assemble the apparatus and knowledge he needed to melt glass beads in a backyard furnace and then to make art by himself, breaking with the glassblowing tradition in which three or four apprentices assisted a craftsman. In 1957 and 1958, he traveled to Paris and Venice, where he saw the small glass working studio of Jean Sala and the many fornaci (glass working furnaces) on the island of Murano. On Murano, Littleton bought blowpipes and other tools that a hot glass studio would require.

Through research sponsored by the Toledo Museum of Art in 1962 he developed equipment and a formula for melting glass at lower temperatures, enabling him to blow glass in a studio rather than in the usual factory setting. This is widely considered to have been the first college-level course offered in the United States in the ancient art of glassblowing. This breakthrough led Littleton to play a major role in introducing glass blowing in college and university craft programs. For the next two years he traveled around the country accepting invitations from artist groups and college art departments interested in seeing his works for themselves. His own program at the University of Wisconsin fostered the talents of a generation of glass artists, including Dale Chihuly and Fritz Dreisbach. During the 1960s and early 1970s, glass programs sprang up at universities, art schools, and summer programs across the country. From the 1970s through the 1980s, the American Studio Glass movement became an international phenomenon.

At the time, at large factories like Steuben Glass Works in upstate New York and at the small ones of Murano, in Italy, fine glassmaking was a collaborative effort: an artist gave his design or model to the factory, and glassmakers reproduced it. But with grants and fellowships and financing from the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, Littleton devised a one-person glass production line.

In 1983 Littleton was awarded the Gold Medal of the American Craft Council. He is the author of “Glassblowing: A Search for Form”, published in 1971.

In a phone interview, Joan Falconer Byrd, Mr. Littleton’s biographer, said Mr. Littleton “considered himself an evangelist of sorts.” He believed, she explained, that making his own glasswork was not enough to kindle the level of interest the medium deserved. “He knew there had to be many artists, many galleries, college courses — a whole infrastructure — for studio glass to become a movement,” she said.

“There were 10 million of us who came back” from the war, he said in an interview, “and suddenly free of our parents, we could go to the university, and we didn’t have to compromise.”

Writing in The New York Times Magazine in 1976, novelist Beth Gutcheon described Littleton as the leader of “a small revolution” in glasswork “that has grown into an American design movement of international importance.”

In a 1999 oral history interview for the Archives of American Art, he compared the centuries-old glassblowing technique craftsmen used in factories with the method he used and taught others. In the old system, he said, “they were taught to make each piece exactly like the previous one.”

In 2012, the 50th anniversary of the founding of the American Studio Glass movement, Littleton was the subject of several solo exhibitions, including one at The Corning Museum of Glass, and his work was exhibited in numerous museums across the country. His own work has been held in public collections and displayed in museums all over the world and includes the first pieces of modern glasswork acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Amber Crested Form” and “Amber Twist,” both purchased in 1977. Some other notable locations his work has been found in include: The Detroit Institute of Arts; Glasmuseet Ebeltoft, Denmark; Museum für Kunsthandwerk, Germany; the Indianapolis Museum of Art; National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Museum of Applied Arts, Prague; the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam; the Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, Sapporo; the Toledo Museum of Art; the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC; and the the Museum Bellrive, Zürich.

In December of 2013, Littleton passed away at the age of 91. His studies resulted in unique, original, and complex works of art in glass that document an extraordinary career.