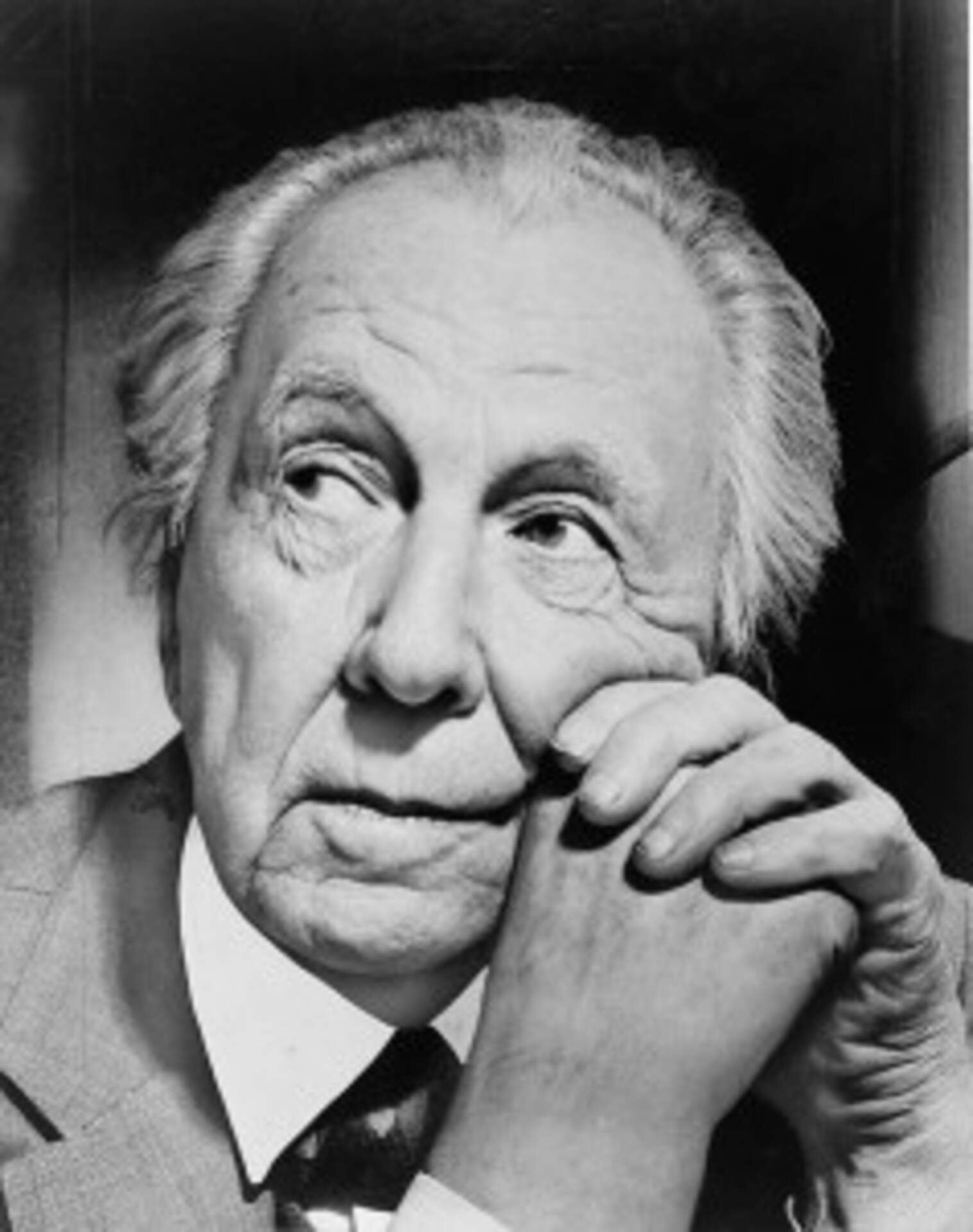

Frank Lloyd Wright

(1869-1959)

Frank Lloyd Wright, born in 1867 near Spring Green, Wisconsin, started his architectural career in Chicago at the age of 19 in the firm of J. Lyman Silsbee, working there for just one year before joining Adler and Sullivan, the firm that would set the course of his career. Louis Sullivan called upon the young architects he hired and mentored to adhere to his famous motto “form follows function,” a tenet that would forever influence Wright’s work. Sullivan, known now as “The Father of Modernism” in American architecture, quickly recognized Wright’s talent and made the young man his leading draftsman.

While working for Sullivan, Wright married Catherine Lee Tobin and built a home in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park. There, he and Catherine became the parents of six children: four boys and two daughters. In 1893, Wright began his own practice and added a studio adjacent to his home. There he attracted other young architects who agreed with his effort to establish a truly American style and develop his Prairie School design emphasizing not just form matching function but the environment as well.

By the time Wright came to Mason City, he had designed many homes which are still recognized as architectural works of art today and had won attention for the Larkin Building and Unity Temple. Prairie School design was at a peak. While he was working on the City National Bank and Park Inn Hotel in 1908, he saw several homes to completion, including a home in Mason City for Dr. C.G. Stockman.

In 1909, however, Wright created a scandal by running off to Europe with Mamah Borthwick Cheney, the wife of a former client. During the two years he spent there, he oversaw the completion of a collection of his built designs up to that time, published in Germany as The Wasmuth Portfolio. These designs, including the City National Bank and Park Inn hotel, impacted the European Modernists greatly and established his reputation not just in the United States, but in the world.

Returning to Spring Green in 1911, Wright began work on a home for Mamah and himself. Not exactly welcomed in his home area because of his relationship with her, he still proceeded to build his famous Taliesin. However, in 1914 Mamah and her two Cheney children were murdered by a crazed servant who also set fire to the house.

Wright managed to rebuild his home and studio and to continue his work. At the time of Mamah’s death, he had already completed the Coonley School Playhouse and was just finishing Midway Gardens, both among his best-known projects. Impressed with and influenced by Japanese design after a trip there during his Oak Park years, in 1915 Wright also undertook the design of Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel, completed in 1923.

During these years, Wright’s style was evolving but especially when he first returned to the United States, commissions were not easy to come by. As he did throughout his career, he struggled through financial setbacks. After Wright’s brief and tumultuous marriage to Mariam Noel, which lasted from 1924-1927, he met and married Oligivanna, a Russian dancer, with whom he would spend the rest of his life. He adopted her daughter Svetlana, and together they had a daughter named Iovanna.

Among his most famous designs soon after this third marriage were Fallingwater in 1935, the Johnson Wax building in 1936, and Taliesin II, his home and architectural school in Arizona, in 1937.

By 1936, Wright’s house designs had changed somewhat into the style commonly called “Usonian” today. He designed about 60 middle-income family homes in this style, typically single-story and often L-shaped to fit around a garden terrace or an unusual geographic setting. Constructed with native materials, flat roofs, natural lighting through clerestory windows, large cantilevered overhangs for passive solar heating and natural cooling, and radiant floor heating, like Prairie School homes, these maintained a close relationship to the environments in which they were built.

Wright continued to work, to speak, and to maintain the architectural center at Taliesin right up to his death in 1959. Price Towers opened in 1952; the Guggenheim Museum, on which he actually started design in 1943, was completed the year of his death.

During his career, Wright designed over 500 buildings: homes, museums, office buildings, hotels, churches and more. The Fellowship, as the group of architects who worked with him came to be called, would also impact the design world long after Wright’s death. While he was first interred in a grave near Unity Temple in Spring Green, Oligivanna’s instructions had his body moved to its final resting place in Arizona beside her and her daughter.

Among the many works on Wright’s life was PBS’s film co-directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. When Novick was asked how Wright’s work changed American architecture, she responded: “How didn’t Frank Lloyd Wright change architecture in America I think is really the way to say it because it is hard to imagine what American architecture would be like or even probably world architecture without Frank Lloyd Wright. There are so many ways and he had so many phases to his career and so many different things he did. There are lots of technical things. There is a way of understanding the human relationship to his space and sense of proportion—what that should be like, and the idea of a home and the importance of that. The list is endless really.”

From http://wrightonthepark.org/about-us/about-frank-lloyd-wright/