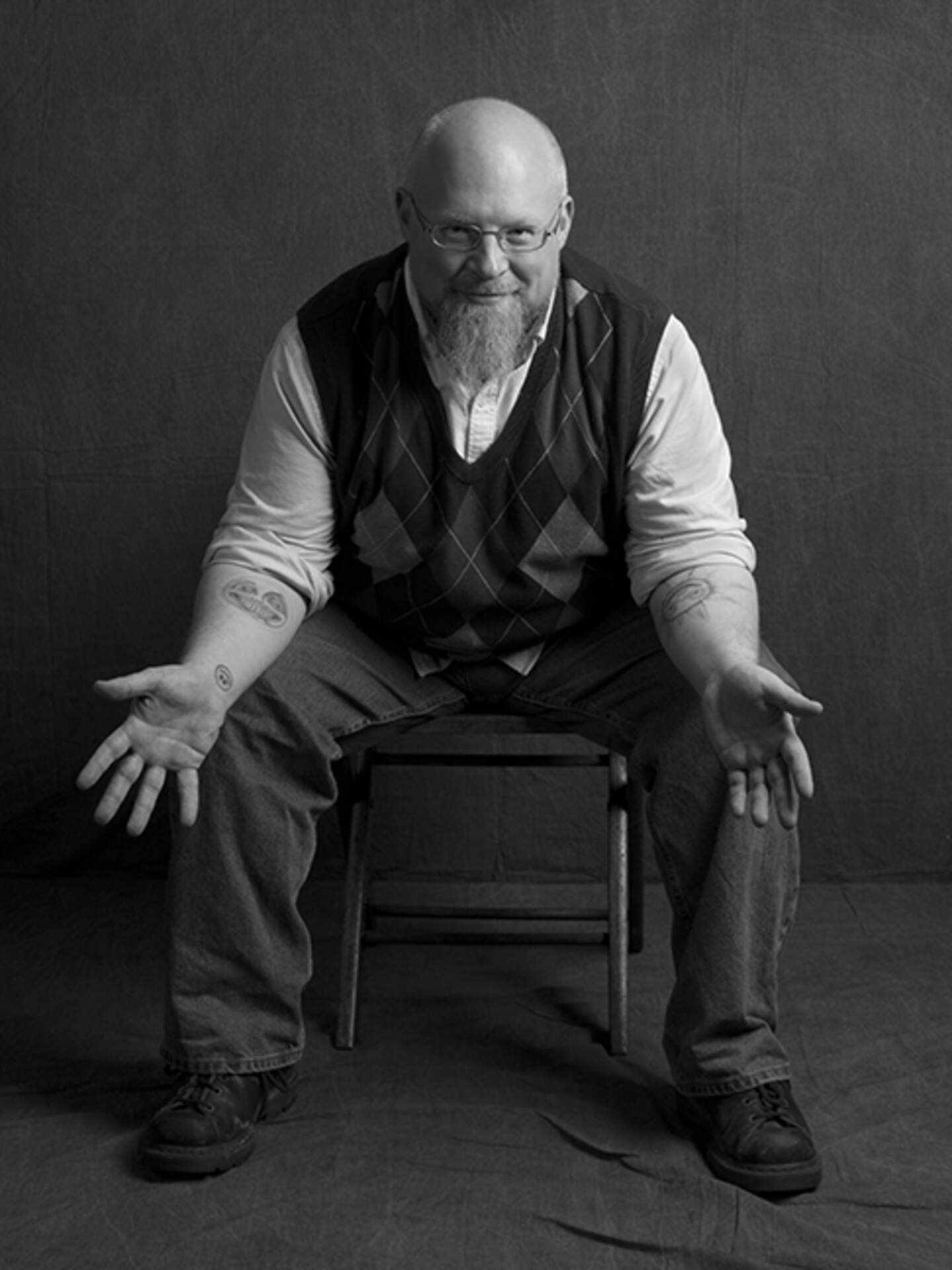

David Moog (b. 1944), A.J. Fries, 2015; Archival inkjet print, 20 x 15 inches; Burchfield Penney Art Center, Gift of the artist, copyright David Moog, 2015

A. J. Fries

(b. 1972)

A.J. Fries is part of the Living Legacy Project at the Burchfield Penney Art Center. Click here to listen to his artist interview or read the transcription below.

A.J. Fries is a painter who was born and raised in Buffalo, N.Y. A graduate of the State University of New York College at Buffalo, he has been called “unquestionably one of WNY’s most serious, developed, and dedicated artists” by Scott Propeack, associate director of the Burchfield Penney Art Center. [1]

In a 2008 profile in Buffalo Rising, Fries recalled that a pivotal moment in his early development as an artist was seeing the retrospective of work by the painter James Rosenquist at the Albright Knox Art Gallery in 1986, when he was a 13-year-old. (Rosenquist is often categorized as part of the Pop Art movement, though he dismisses the term. Nonetheless, his oversized canvases depicting consumer goods and pop culture icons would appear to be a clear influence on Fries’s own imagery years later.) The exhibition made such an impression on him that he visited the show multiple times, befriending the museum guards and spending many hours studying it. The sight of other attendees paying scant attention to the work sometimes provoked him to throw pencils at them, he says, presumably as a (characteristically playful but undeniably pointed) lesson to them in engaging more fully with art. [2]

The work that first brought Fries to the attention of Buffalo’s art community was a loose series of detailed, larger-than-life paintings of mass-produced snack foods and homemade dessert items in the early 2000s. (The term “series” may be misleading, because Fries has pointed out that he does not conceive of his output in that way, preferring the expression “bodies of work.” [3]) The artist followed these with another group of works depicting sex toys, often juxtaposed with pages from coloring books and other markers of childhood. Looking back at this body of work in light of what would come later, Hallwalls curator John Massieronce wrote, “[Fries’s] paintings of a slice of pie, a package of Twinkies, or a purple vibrating dildo were not cheeky monkeys seeking to merely amuse or titillate the viewer, but were always really about something else. When I wrote about those works, I thought the something else was Desire. I still do. Nostalgic Desire, Humorous Desire, Sexual Desire, Undefined Desire. But the new paintings suggest something wider than that…” [4]

The “something wider” Massier had in mind was the common thread connecting Fries’s colorful, Pop-referencing early paintings with the primarily monochromatic, even more detailed representations of blatantly mundane surfaces that he began producing sometime around 2006. The curator describes the subjects of this new work as “objects—more appropriately, moments—so banal that their initial fascination might be the fact that anyone bothered to paint them at all. Water on tiles. A soap bubble. A lightbulb on the ceiling. Water descending down a drain. Clouds framing a streetlamp. … While Fries has painted these new works with an impressive seeming-reality, they are far less about realistic pictorial representation than about the ephemeral and gossamer moments captured.” [5]

In discussing his shift to a much more limited palette, Fries recalls that he “took the color out to take out the emotion that people attach to color. Some people have an emotional attraction to color that I would have to fight against. I’m too lazy for that. It’s hard enough to get a person to stand still in front.” [6]

The fact that the new images were black and white (an inherently anti-realistic choice) was balanced by their heightened degree of detail. Writer Elena Cala Buscarino puts it this way: “When you realize that you’re looking at a painted image, not a photograph, something fires in your brain; your head canters to the side, and there’s an almost uncomfortable sense of trying to right yourself in front of something that you know is a painting while another part of you thinks, No. No way. No one can paint a pile of clear bubbles like that. Or, No way in hell is that not a photograph of water droplets on stainless steel. You can almost smell the bubble soap, almost feel the wetness of the drops of water on cold metal that are reflecting a thousand different images at you through their mirrored, convex surfaces.” [7]

The tool that enabled Fries to capture such fleeting moments was the digital camera he obtained around the same time. [8] (For a while he kept it duct-taped to the steering wheel of his car, so that he could shoot views of roads and bridges while driving.) He developed a technique that writer Ron Ehmke summarizes this way: “Fries begins a painting by taking dozens, sometimes hundreds, of reference photos …, putting them away while he ‘forgets’ them, pulling them out again months later to cull a smaller number, putting those away and forgetting them again, then making a final selection. The process, then, is something like what happens when we convert lived experience into memory, and then transform the memories into an anecdote we tell other people. With the passage of time, what really happened grows fuzzier, and details get rearranged to suit a new context.” [9]

Given the uncanny verisimilitude of his paintings, Fries is often called a photorealist, but in a 2009 blog entry he notes, “It always bothers me when people say that my work is photorealistic, because I just don't see it. I want to sit them down and show them true photorealistic work and show them the difference. The point of my work is not to reproduce the photo that I took, but more the moment that the photo was taken, or more to the point the spark in my brain that led me to take the photo. The surface of my work is usually very dry and rough; the texture of the canvas is visible. I guess I want that texture to interfere with the image that people see.” [10]

Of this body of work, Massier writes, “There is a dreamy haze layered over these images, a soft focus, like something only half remembered. The subjects of the paintings are all off-centered, sometimes almost as though they were sliding in or out of the picture frame. While they might obviously be connoting the idea of memory, Fries’s act of recollection is not pursuing a memory of these scenes or objects. These are decoys because what Fries is ultimately pursuing is a sensation. It is not about painting things but painting time. And not Time Passing. The stillness of the images might suggest that, but this is another ruse. It is Time Suspended. Or Time Expanded. Or Time Amplified. … There is the sensation of expansion and awareness and something sublime that exists in that instant. It is the sensation of being wholly in the moment and it is that sensation for which Fries’s paintings pine.” [11]

Fries has exhibited in Buffalo at the Burchfield Penney Art Center, Buffalo Arts Studio, Hallwalls, and Big Orbit Gallery, among others. His work is included in many public and private collections, including those of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery and the Burchfield Penney. In 2001 he was awarded a 3-month residency at the International Studio and Curatorial Program in New York, and in 2007 he received a full fellowship for a month-long residency at the Vermont Studio Center. He is a founding member of Trans Empire Canal Corporation (TECC), a Buffalo-based collective responsible for the Burchfield Penney Art Center’s 2014 multi-year project “Cultural Commodities: As Exhibition in Four Phases,” informally referred to as the “art barge.” Fries was designated one of the Burchfield Penney’s first Living Legacy artists in 2012.

To see more examples of A. J. Fries’s work, visit ajfriesart.com.

[1] Scott Propeack, “The Artists are Among Us,” blog entry on the Burchfield Penney Art Center website, 06/04/2012, http://www.burchfieldpenney.org/general/blog/article:06-04-2012-12-00am-the-artists-really-are-among-us/. (Accessed 08/26/2013)

[2] Elena Cala Buscarino, “A. J. Fries: Artistic Genius,” Buffalo Rising, 07/22/ 2008, http://buffalorising.com/2008/07/aj-fries-artistic-genius/. (Accessed 08/26/2013)

[3] A. J. Fries, video interview “A. J. Fries at Big Orbit Gallery” on the Buffalo News website, n.d. (presumably 12/2012), http://util.buffalo.com/video/?video=2028782038001. (Accessed 08/26/2013)

[4] John Massier, “The Sweet Spot,” catalogue essay accompanying the exhibition Ignoring the Sirens at Hallwalls, 11/06-12/18/2009. PDF available at http://www.hallwalls.org/pubs/122.html. (Accessed 08/26/2013)

[5] John Massier, “The Sweet Spot.”

[6] A. J. Fries, quoted in Elena Cala Buscarino, “A. J. Fries: Artistic Genius.”

[7] Elena Cala Buscarino, “A. J. Fries: Artistic Genius.”

[8] Elizabeth Licata, “Because He Can,” catalogue essay accompanying the exhibition Light in Shadow at Big Orbit Gallery, 12/01/2012-01/21/2013.

[9] Ron Ehmke, “Guy Walks Into a Bar …,” catalogue essay accompanying the exhibition Light in Shadow at Big Orbit Gallery, 12/01/2012-01/21/2013.

[10] A.J. Fries, “after a year,” blog entry at Empty Sentiments, 08/18/2009, http://emptysentiments.blogspot.com/. (Accessed 08/27/2013)

[11] John Massier, “The Sweet Spot.”

Listen or read A. J. Fries's interview with Heather Gring of the Burchfield Penney Art Center conducted on June 5th, 2012. Fries discusses many aspects of being an artist and the contemporary art scene with a level of humor and honesty that is both rare in general and characteristic of him. From making the decision at a young age to pursue art as a career, to dealing with his colorblindness and his innate dislike of people, why he loved the Clyfford Still room at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, and how his seemingly simplistic photo-based paintings really represent the artist’s complex notions of time, the interview will take you through the life and mind of a man who has devoted his life to art and has made refreshing discoveries along the way.

Hear Fries utter one-liners (like “I never want to paint my best painting,” “fail constantly,” and “work more, sacrifice for it”) which tend to be as inspiring as they are hilarious. His beliefs and theories on the process of art making are just as poignant: “learn the rules, then you can fuck the rules.”

This interview is recommended for mature audiences only.