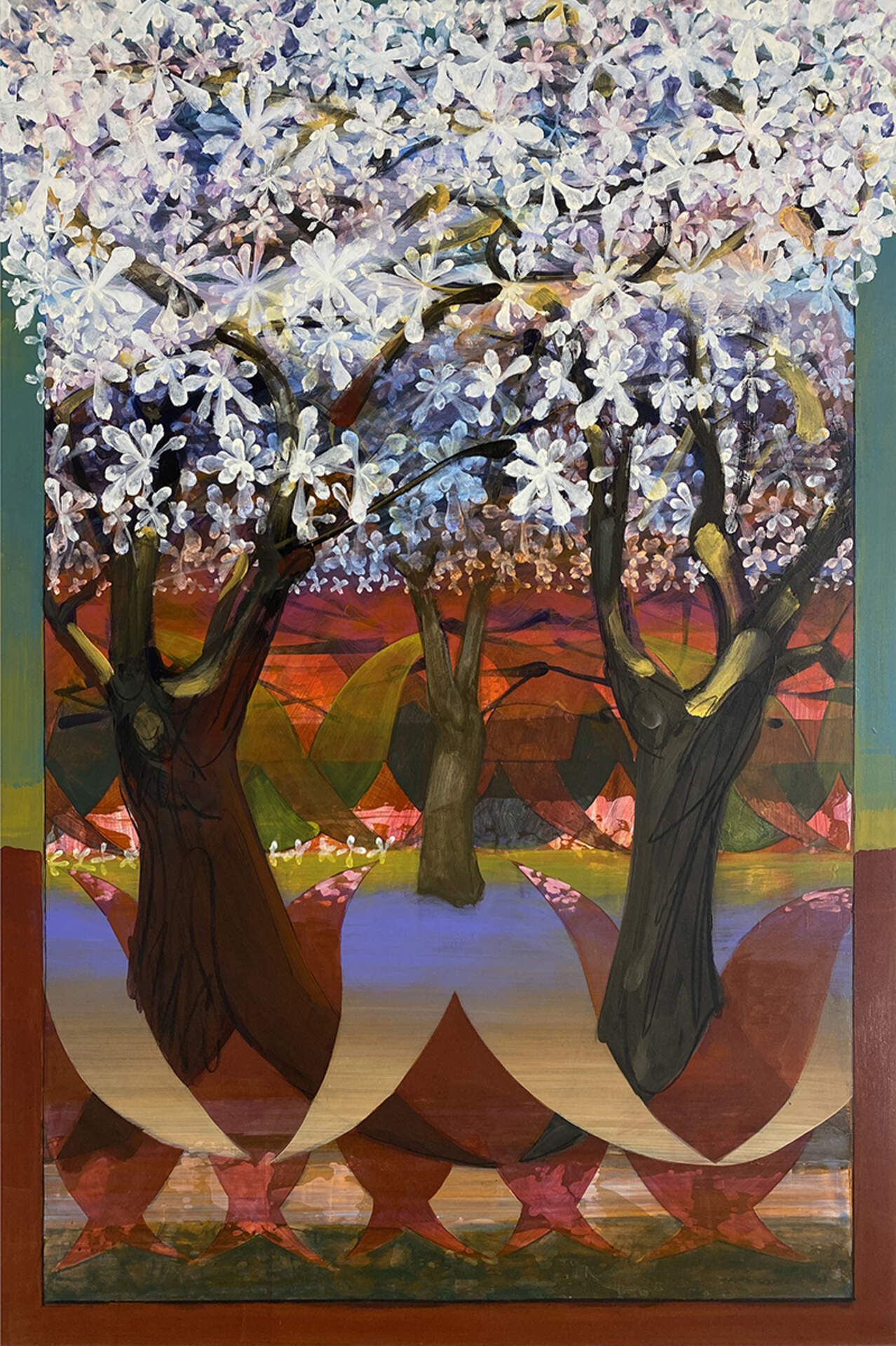

Mike Glier (b. 1953)Trees Sharing Information v.6

2022

acrylic and charcoal on panel

60” x 40”

Courtesy of Downing Yudain Gallery, North Stamford, CT

TREES SHARING INFORMATION

MG: Nancy, when I first read about trees sharing information in Richard Power’s novel, The Overstory, I was completely taken by the idea that the forest is not simply a place of competition for resources, but also a place of interspecies cooperation! Intrigued, I read more about Suzanne Simard, the forest scientist whose groundbreaking research started this revolution. Evidently, trees communicate underground through fungal networks, facilitating the exchange of carbon, water, nutrients and defense signals between trees. Moreover, some dying trees don’t just rot, but share up to 40% of their carbon to neighboring trees to support the health of the forest before they die. Trees also communicate through volatile organic compounds that are released into the air to notify trees downwind of insect attack! Simard’s book, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest, is a good source for more information as is The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben. More recently, scientists are exploring the role of electrophysiology and sentience in plants.

NW: Learning that you painted several versions of “Trees Sharing Information” immediately struck a chord with me as a nod to Suzanne Simard’s ground-breaking research and phenomenal book. I initially learned about her work through her 2016 Ted Talk “How trees talk to each other” broadcast on NPR—which was mind-blowing. I ordered her book, which was also a revelation about how many people resisted accepting her scientific findings.

MG: Nancy, how does this research affect your understanding of Burchfield’s oeuvre and more specifically, Dawn of Spring?

NW: Burchfield’s reverence for trees, the cycle of life, and earth’s invigorated seasonal changes are exemplified in Dawn of Spring. Confers like the black spruce can grow up to 60 feet tall. They can propagate when heavy snow forces the lowest branches to touch the ground, which take root and create a ring of small trees around its base. Suggested in the drawing on the left side of the painting, a desiccated tree trunk that Burchfield planned to add to the expanded composition represents the elder in this life cycle, whose decomposition in an old-growth forest will feed and harbor a microscopic world of life forms. An arc of warm sunlight on the horizon announces dawn approaching, its warm glimmers heralding the rebirth season.

MG: Artists can support science by creating images that tell the story of their research and help spread the word.

NW: As a forest ecologist, Simard also used a bit of humor, coining the term “the wood wide web” in an article in the journal Nature in 1997. It rolls off the tongue easier than saying “the complex ways that trees and mushrooms communicate and share resources through mycelium networks, or mycorrhizal fungi.”

MG: Since Dr. Simard first published her findings in 1997, Burchfield most certainly did not know that trees can share information and resources. But to look at Dawn of Spring, you’d think he’d just run from her classroom, and in an excited rush, visualized her research! The Mother tree is haloed and bristling with spikes and scimitars that extend into the air and soil in which she is rooted. To suggest familial bonds, the sapling has these same motifs. They express his animist proclivities; the dirt, the snow, the wood, and the air all vibrate with the energy of the woods that Burchfield felt rather than saw. His artistic practice is an example of how imagination can be a form of speculation that can lead to rational investigation and fact. I like how these tree pictures parallel a truth about human culture; competition is necessary, but not as essential as cooperation. The trees are telling us to get it together and talk to one another and to share resources, since it’s ultimately good for everyone!