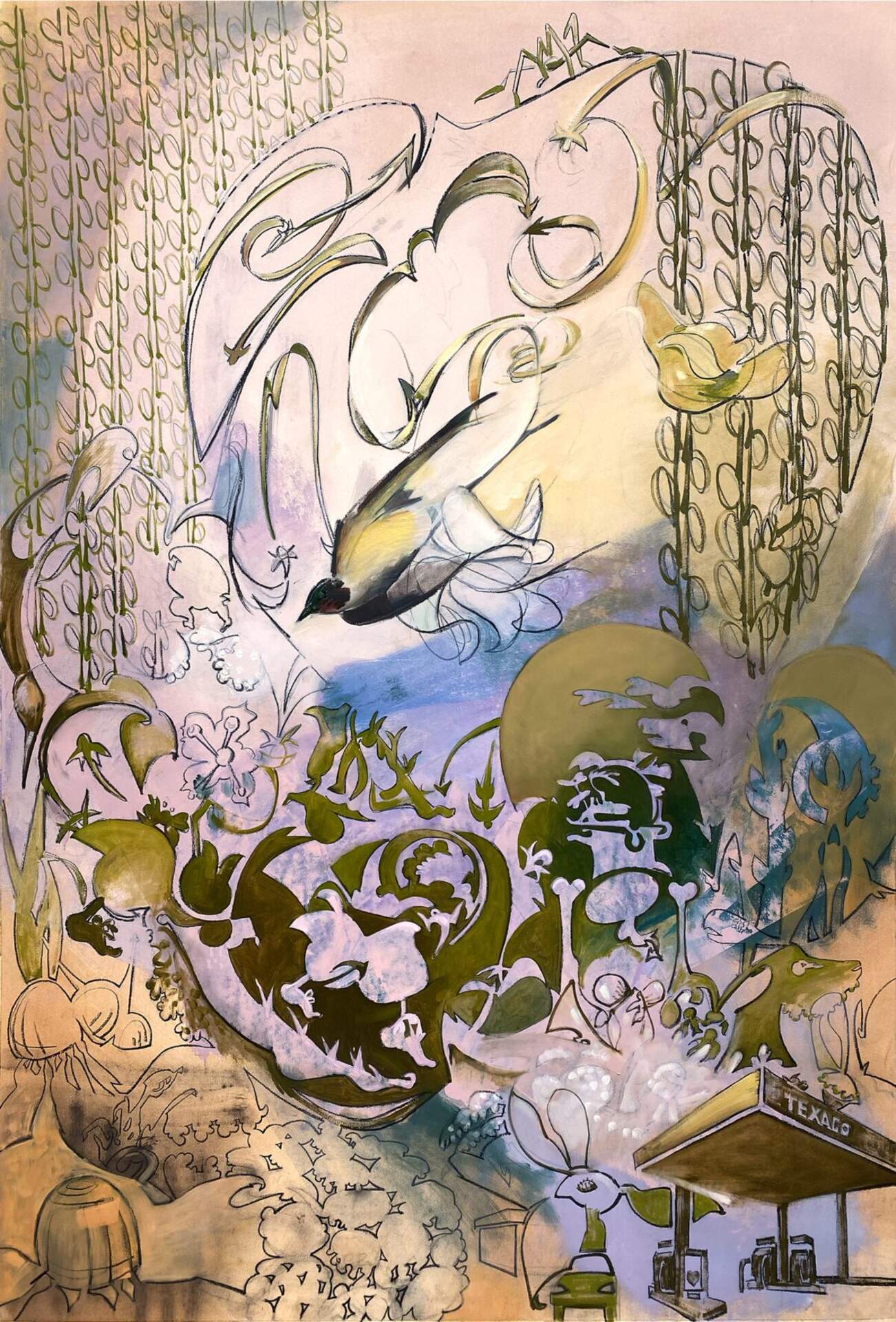

Mike Glier (b. 1953)There Is a Faint Odor of Petroleum and the Birds Are Singing, v.2

2021

oil and charcoal on Arches watercolor paper mounted on fabric

72 ½" x 49 ½”

Burchfield Penney Art Center, Purchased with funds from the Art Endowment Fund, 2025

COMMENTARY

MG: We selected these paintings as examples of a critical approach to landscape painting. The plumes of smoke in the Burchfield are beautiful, if you ignore the pollution that is spreading. Only four decades before this picture was painted in 1916, Pissarro and Monet were celebrating smoky factories and steamy train stations as signs of modern progress. Are we sure that Burchfield had critical intentions with Rising Smoke?

NW: In this case, yes, Burchfield had critical intentions to show how close local factory smoke came to his modest Salem, Ohio neighborhood. Some of his steam engine paintings, like The White Plume, reflect a nostalgic romanticism for train travel and westward expansion. This early 20th-century optimism fed the misconception that industrialization would ease the travails of manual labor. However, more often he presented disturbing images of desecrated landscapes with hellish visions of burning hillside coke ovens, sinister coal mines in stark surroundings, dye and chemical-tainted waterways, and factories belching dark, acidic smoke.

Your painting also partially conceals the pollution until you consider the brown passages and read the title. The design is so lyrically beautiful that you’re easily drawn in before getting hit by the message.

MG: My picture was composed in England. I was sitting on the banks of the River Brue, drawing the snowdrops, watching birds and listening to the sounds of the river. It was bucolic, but for the faint odor of the gas station hidden in trees across the street. The pretty pink, lavender, and blue in the bottom half are the colors of light on an oil slick. Like I said before, beauty is amoral.