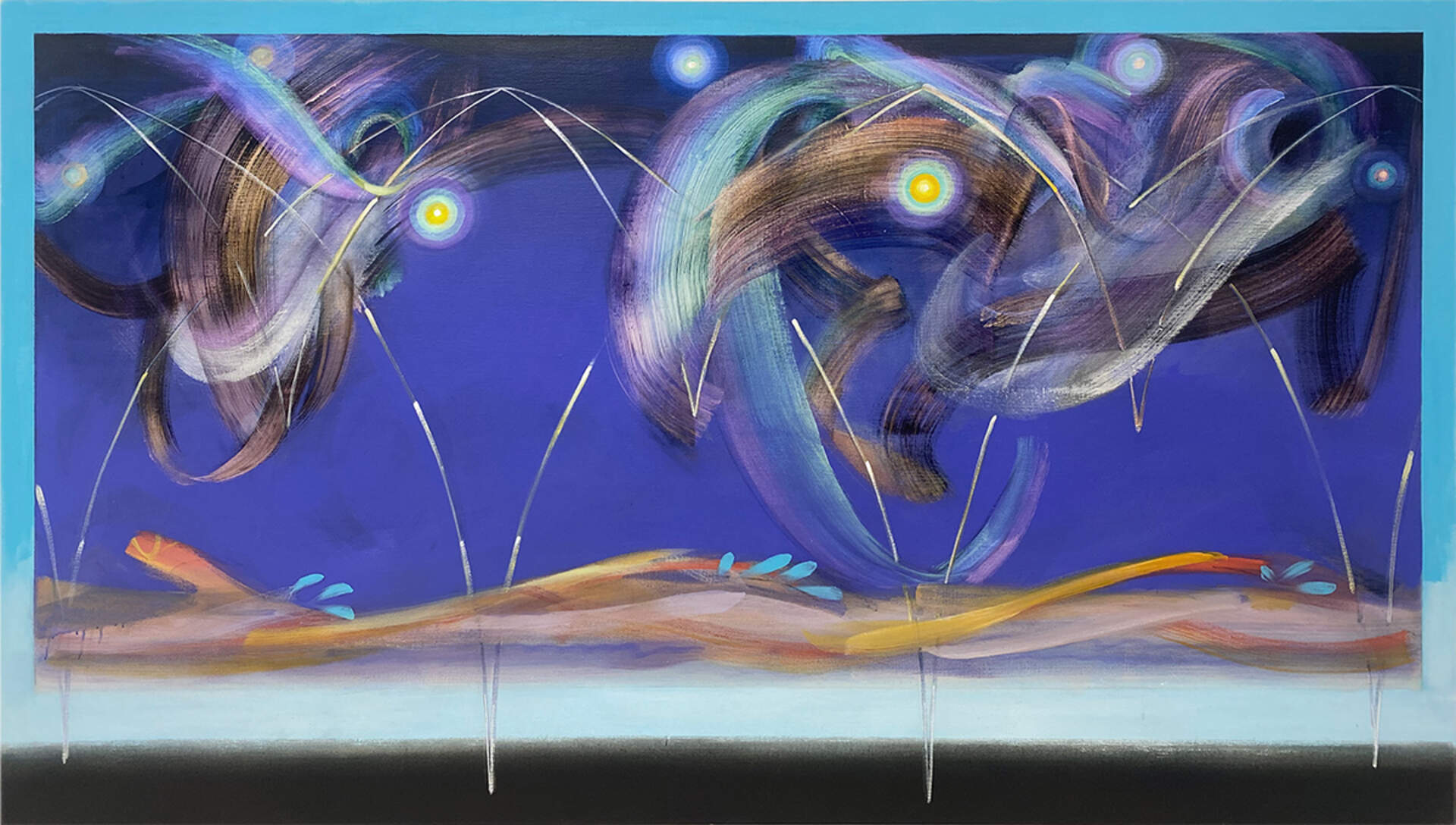

Mike Glier (b. 1953)The Evensong of Animals

2023

acrylic on linen

48 x 84 inches

Courtesy of Downing Yudain, North Stamford, CT

MODERNISM, BEAUTY, UGLINESS, AND MAGIC

MG: I am very excited to have A Dream of Butterflies in the exhibition!

NW: Me too! I have never seen A Dream of Butterflies in person. Dream imagery like this is so vivid and joyful, the brain’s way of manifesting and intensifying actual experiences. Charles and Bertha Burchfield’s serendipitous trip to the countryside on June 22, 1962, reflects a plausibly influential event. They packed a picnic lunch and ventured to a quiet spot. He sets the stage by noting: “We enjoyed watching the various insects busy here— orange-tan and brown skippers, 4 or 5 of them; tiny young grasshoppers; a miniature tree-frog, and beautiful small dragon-flies with invisible wings, rich cerulean at the head graduating to metallic emerald blue green at the tail, the brilliant color cut by narrow segments of dark gray — these were a delight to watch.” Not only was this visually idyllic, but lilting sounds also enriched their experience. “From the depths of the woods close by a wood-thrush sang intermittently. Once a “blue” (butterfly) fluttered in erratic flight past us.” This resonated in his unconscious mind because he dreamt of “Albino” Monarchs–an image so powerful he was compelled to paint it.

MG: This painting is modern and so beautiful. On the first count it’s clear that Burchfield’s design sensibilities are modernist in that he limits volumetric forms in favor of flat shapes and creates the illusion of depth by overlapping forms and softening edges and contrasts as he develops deep space. Linear perspective is left at the door and replaced with dramatic changes of scale to suggest spatial relationships. But like all good modernists of the twentieth century, he plays with these variables in unexpected ways, like making the butterflies and the flowering plant enormous in relation to the trees!

NW: Burchfield was first identified as a modernist in April 1930, when Director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. gave him the first solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Established November 7, 1929, MoMA was “the first institution anywhere in the United States to devote itself exclusively to Modern art.” The exhibition focused on his early watercolors from 1916-1918. Barr admired how Burchfield’s “romantic qualities or vices” were overshadowed by strong design, conviction, and youthful inventiveness.

MG: Ha, “Vices”! High Modernist critical language was bracing!

NW: A Dream of Butterflies demonstrates how that aesthetic continued. He resists being a realist because there is so much more to the experience that mediates the senses and enters a more symbolic realm. In this work, he sets up a pattern of black woodland depths dancing across a stand of beech trunks. Cascading golden leaves move rhythmically in counterpoint to the butterflies. Looking closer, note how the eye patterns and radiating crescents on butterfly wings mimic tree eyes, and leaf edges, and the linear articulation of flowers and stems that float into the air. Even the grass quivers.

MG: The Evensong of Animals is also beholden to modernist principles of design, and like Burchfield I’m totally happy moving from traditional representation to abstraction when it feels right. On this front, Burchfield looks a bit ahead of his time, since he ignored 20th-c. pressures to conform to modernist style and pursued a visual style that tripped lightly through the conventions of representation and modernism, choosing flexibility over conformity.

NW: Tell me more about what you are representing.

MG: My painting began on a spring night when the Peepers in the pond in front of my house were in full chorus. It was a full-throated mating song, loud enough to travel up into the sky. I imagined the sound floating up into space, past the atmosphere to travel forever. My imagination is wrong, of course. Sound waves need a medium like air, and space is a vacuum. Nevertheless, I continued with the fantasy and began to think about all the sounds that animals make as they prepare for the transition from day to night, and the great chorus of growls, snuffles, roars and tweets that rise into the sky.

NW: You both represent imaginary scenes. While Burchfield’s depends on viewers being drawn in by identifying with its exuberance, you challenge them to suspend reality and realize wider implications.

MG: Both pictures in this comparison are fantasies formed in observation of the natural world; the Burchfield is beautiful to my eye, and I tried to make mine beautiful as well. But beauty is a troubled subject in modern art. The argument, greatly simplified, goes something like this. The ancient Greeks established an equivalency between physical beauty and moral perfection. A symmetrical face and a well-proportioned body were physical manifestations of virtue and order. This fallacy was transmitted to the Roman era and then to the Renaissance and persists into the present, not as marble statues of graceful Venuses and hunky Davids, but as a tool of capitalism, which uses beauty to seduce the public and sell fantasies.

But beauty, like a storm, is amoral and apolitical. It can be used by capitalists, fascists or communists alike to promote ideology. Some have proposed that ugliness, by virtue of it being the opposite of beauty, is morally superior and that ugly art is virtuous. Horse Manure!! Ugliness can also be used to manipulate and promote hateful ideology. Art that is abject, chaotic and ugly is important, since it can embody human experience, but it is not inherently virtuous!

The third painting in this group, When the last monarch leaves New York this painting will shake and moan, definitely uses the beauty of the monarch butterfly to sell my ideology!

NW: Your message about the monarch butterfly is sure to connect with viewers concerned about climate change. The monarch has become iconic in representing fragility and vulnerability, the proverbial canary in a coal mine. As someone fortunate enough to have witnessed a spectacular “butterfly tree”—when literally thousands of monarchs cover a single tree to rest during their migration from North America to Mexico—I am attuned to their threatened existence.

MG: I don’t believe this painting will shake and moan; I don’t believe in magic, but in this painting, it seemed fair to employ the power of this primordial, human delusion to fight for preservation of the natural world. Magic is a way for humans to understand and have agency in a chaotic and often hostile world, so why not use it to prevent more chaos and destruction.