Paul Sharits (1943-1993)Untitled (The Resignation of General Washington)

Article on paper

15 x 11 1/2 inches

Gift of Christopher and Cheri Sharits, 2006

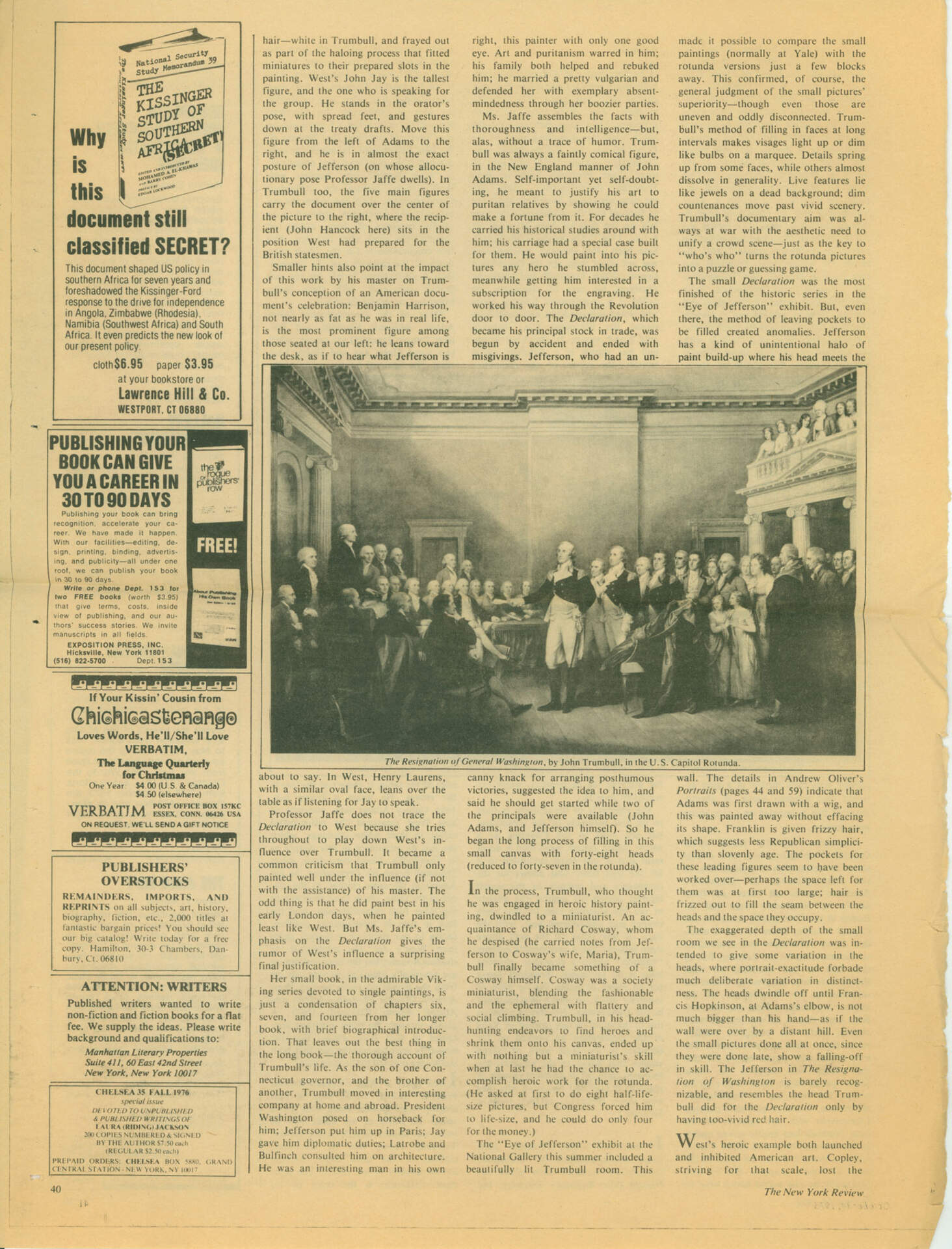

hair—white in Trumbull, and frayed out as part of the haloing process that fitted miniatures to their prepared slots in the painting. West’s John Jay is the tallest figure, and the one who is speaking for the group. He stands in the orator’s pose, with spread feet, and gestures down at the treaty drafts. Move this figure from the left of Adams to the right, and he is in almost the exact posture of Jefferson (on whose allocutionary pose Professor Jaffe dwells). In Trumbull too, the five main figures carry the document over the center of the picture to the right, where the recipient (John Hancock here) sits in the position West had prepared for the British statesmen.

Smaller hints also point at the impact of this work by his master on Trumbull’s conception of an American document’s celebration: Benjamin Harrison, not nearly as fat as he was in real life, is the most prominent figure among those seated at our left: he leans toward the desk, as if to hear what Jefferson is about to say. In West, Henry Laurens, with a similar oval face, leans over the table as if listening for Jay to speak.

Professor Jaffe does not trace the Declaration to West because she tries throughout to play down West’s influence over Turnbull. It became a common criticism that Turnbull only painted well under influence (if not with the assistance) of his master. The odd things is that he did paint best in his early London days, when he painted least like West. But Ms. Jaffe’s emphasis on the Declaration gives the rumor of west’s influence a surprising final justification.

Her small book, in the admirable Viking series devoted to single paintings, is just a condensation of chapter six, seven, and fourteen from her longer book, with brief biographical introductions. That leaves out the best thing in the long book—the thorough account of Trumbull’s life. As the son of one Connecticut governor, and the brother of another, Trumbull moved in interesting company at home and abroad. President Washington posed on horseback for him; Jefferson put him up in Paris; Jay gave him diplomatic duties; Latrobe and Bulfinch consulted him on architecture. He was an interesting man in his own right, this painter with only one good eye. Art and puritanism warred in him; his family both helped and rebuked him; he married a pretty vulgarian and defended her with exemplary absentmindedness through her boozier parties.

Ms. Jaffe assembles the facts with thoroughness and intelligence—but, alas, without a trace of humor. Trumbull was always a faintly comical figure, in the New England manner of John Adams. Self-important yet self-doubting, he meant to justify his art to puritan relatives by showing he could make a fortune from it. For decades he carried his historical studies around with him; his carriage had a special case built for them. He would paint into his pictures any hero he stumbled across, meanwhile getting him interested in a subscription for the engraving. He worked his way through the Revolution door to door. The Declaration, which became his principal stock in trade, was begun by accident and ended with misgivings. Jefferson, who had an uncanny knack for arranging posthumous victories, suggested the idea to him, and he should get started while two of the principals were available (John Adams, and Jefferson himself). So he began the long process of filling in this small canvas with forty-eight heads (reduced to forty-seven in the rotunda).

In the process, Trumbull, who though he was engaged in heroic history painting, dwindled to a miniaturist. An acquaintance of Richard Cosway, whom he despised (he carried notes from Jefferson to Cosway’s wife, Maria), Trumbull finally became something of a Cosway himself. Cosway was a society miniaturist, blending the fashionable and the ephemeral with flattery and social climbing. Trumbull, in his headhunting endeavors to find heroes and shrink them onto his canvas, ended up with nothing but a miniaturist’s skill when at last he had the chance to accomplish heroic work for the rotunda. (He asked at first to do eight half-life size pictures, but Congress forced him to life-size, and he could do only four for the money.)

The “Eye of Jefferson” exhibit at the National Gallery this summer included a beautifully lit Trumbull room. This made it possible to compare the small paintings (normally at Yale) with the rotunda versions just a few blocks away. This confirmed, of course, the general judgment of the small pictures’ superiority—though even those are uneven and oddly disconnected. Trumbull’s method of filling in faces at long intervals makes visages light up or dim like bulbs on a marquee. Details spring up from some faces, while others almost dissolve in generality. Live features lie like jewels on a dead background; dim countenances move past vivid scenery. Trumbull’s documentary aim was always at war with the aesthetic need to unify a crowd scene—just as the key to “who’s who” turns the rotunda pictures into a puzzle or guessing game.

The small Declaration was the most finished of the historic series in the “Eye of Jefferson” exhibit. But, even there, the method of leaving pockets to be filled created anomalies. Jefferson has a kind of unintentional halo of paint build-up where his head meets the wall. The details in Andre Oliver’s Portraits (pages 44 and 59) indicate that Adams was first drawn with a wig, and this was painted away without effacing its shape. Franklin is given frizzy hair, which suggests less Republican simplicity than slovenly age. The pockets for these leading figures seem to have been worked over—perhaps the space left for them was at first too large; hair is frizzed out to fill the seam between the heads and the space they occupy.

The exaggerated depth of the small room we see in the Declaration was intended to give some variation in the heads, where portrait-exactitude forbade much deliberate variation in distinctness. The heads dwindle off until Francis Hopkinson, at Adam’s elbow, is not much bigger than his hand—as if the wall were over by a distant hill. Even the small pictures done late, show a falling-off in skill. The Jefferson in The Resignation of Washington is barely recognizable, and resembles the head Trumbull did for the Declaration only by having too-vivid red hair.

West’s heroic example both launched and inhibited American art. Copely, striving for that scale, lost the