Paul Sharits (1943-1993)Untitled (Declaration of Independence)

Article on paper

15 x 11 1/2 inches

Gift of Christopher and Cheri Sharits, 2006

Copely was paying his dues to the West aesthetic with his Death of the early of Chatham and the Death of Major Pierson. Luckily for Turnbull, the Americans lost most of their early battles; so he could prove they were going to win by painting the deaths of General Warren at Bunker Hill and of General Montgomery at Quebec. (He also began The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton-but this suffered from his documentary-commercial impulse: he delayed it to perfect it. After his student days he constantly tried to expand his art in ways that shrank it.) All the elements West had assembled are present in Trumbull’s Bunker Hill, the smoke of whose guns Trumbull had seen from a distance. But Trumbull is less classical and composed than West—his figures have a greater dash of realism. If West painted like a modern Plutarch, Trumbull was Plutarch as war correspondent: three men struggle with the bayonet poised just above General Warren’s breast. The Death of Montgomery goes even farther in a gory activism that suggests Goya. A ghostly shred of flag is impaled on a tree above Montgomery.

Americans, regularly losing under General Washington, had their doubts about the celebration of such defeats, so the first pictures of Trumbull’s American series—all three of them Deaths of Americans—were not included in the final public series for the Capitol rotunda. There he had to abandon Dying Americans and concentrate on Surrendering to the British Leaders. But by that time he had stumbled on what should have been his greatest theme: the surrendering by Washington of his military commission. Here was the symbolic death that in no way marred one’s victory. Here was bourgeois nobility raised higher than any aristocrat’s. The lone commander stands before the central pilaster that supports the whole scene—yet he stands there to give up his power. The very year of Washington’s resignation, Trumbull painted a classical Cincinnatus with the features of the man Trumbull had briefly served under. In the rotunda, he would create Cincinnatus in modern dress, the ideal fulfillment of West’s program. But by then practically no one would notice what he was up to.

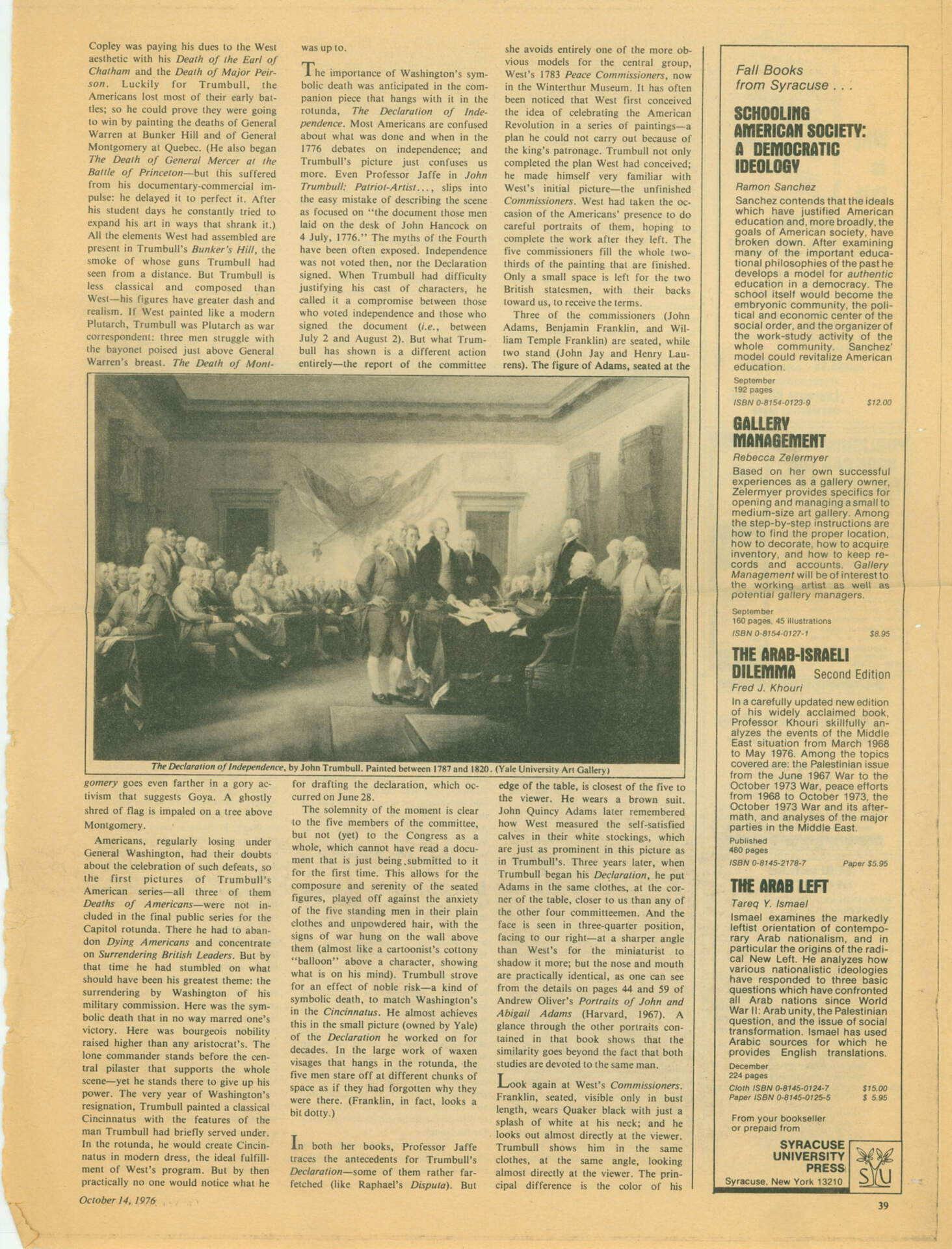

The importance of Washington’s symbolic death was anticipated in the companion piece that hangs with it in the rotunda, The Declaration of independence. Most Americans are confused about what was done and when in the 1776 debates on independence; and Trumbull’s picture just confuses us more. Even Professor Jaffe in John Trumbull: Patriot-Artist…, slips into the easy mistake of describing the scene as focused on “the document those men laid on the desk of John Hancock on 4 July, 1776.” The myths of the Fourth have been often exposed. Independence was not voted then, nor the Declaration signed. When Trumbull had difficulty justifying his cast of characters, he called it a compromise between those who voted independence and those who signed the document (i.e., between July 2 and August 2). But what Trumbull has shown is a different action entirely—the report of the committee for drafting the declaration, which occurred on June 28.

The solemnity of the moment is clear to the five members of the committee, but not (yet) to the Congress as a whole, which cannot have read a document that is just being submitted to it for the first time. This allows for the composure and serenity of the seated figures, played off against the anxiety of the five standing men in their plain clothes and unpowered hair, with the signs of war hung on the wall above them (almost like a cartoonist’s cottony “balloon” above a character, showing what is on his mind). Turnbull strove for an effect of noble risk—a kind of symbolic death, to match Washington’s in Cincinnatus. He almost achieves this is the small picture (owned by Yale) of the Declaration he worked on for decades. In the large work of waxen visages that hangs in the rotunda, the five men stare off at different chunks of space as if they had forgotten why they were there. (Franklin, in fact, looks a bit dotty.)

In both her books, Professor Jaffe traces the antecedents for Turnbull’s Declaration—some of them rather farfetched (like Raphael’s Disputa). But she avoids entirely one of the more obvious models for the central group, West’s 1783 Peace Commissioners, now in the Winterthur Museum. It has often been noticed that West first conceived the idea of the American Revolution in a series of paintings—a plan he could not carry out because of the king’s patronage. Turnbull not only completed the plan West had conceived; he made himself very familiar with West’s initial picture—the unfinished Commissioners. West had taken the occasion of the Americans’ presence to do careful portraits of them, hoping to complete the work after they left. The five commissioners fill the whole two-thirds of the painting that are finished. Only a small space is left for the two British statesmen, with their backs toward us, to receive the terms.

Three of the commissioners (John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and William Temple Franklin) are seated, while two stand (John Jay and Henry Laurens). The figure of Adams, seated at the edge of the table, is closest of the five to the viewer. He wears a brown suit. John Quincy Adams later remembered how West measured the self-satisfied calves in their white stockings, which are just as prominent in this picture as in Trumbull’s. Three years later, when Trumbull began the Declaration, he put Adams in the same clothes, at the corner of the table, closer to us than any of the four committeemen. And the face is seen in three-quarter position, facing to our right—at a sharper angle than West’s for the miniaturist to shadow it more; but the nose and mouth are practically identical, as one can see from the details on pages 44 and 59 of Andre Oliver’s Portraits of John and Abigail Adams (Harvard, 1967). A glance through the other portraits contained in that book shows that the similarity goes beyond the fact that both studies are devoted to the same man.

Look again at West’s Commissioners. Franklin seated, visible only in bust length, wears Quaker black with just a splash of white at his neck; and he looks out almost directly at the viewer. Trumbull shows him in the same angle, looking almost directly at the viewer. Trumbull shows him in the same clothes, at the same angle, looking almost directly at the viewer. The principal difference is the color of his