Paul Sharits (1943-1993)Sharits Demystifies Flim

photocopy on paper

14 x 8 1/2 inches

Gift of Christopher and Cheri Sharits, 2006

Sharits Demystifies Film

Paul Sharits brings the nuts and bolts of filmmaking into every frame

By Stephen Godfrey

IF SOME OF avant-garde filmmaker Paul Sharits’ works were shown to an unsuspecting movie theater audience, they would bring shouted demands from the audience for a new projectionist, or grumbled protests about the lousy quality of the print. The edges of the projector lens are filed so that the sprockets show on the screen. Strips of film are superimposed on each other, and long scratch marks may appear over pure patches of color. Sometimes the film flickers, now with the intensity of a strobe light, now as if an outside storm were interfering with the power source. Basic structural devices, like beginnings, middles and ends, play a minor roll. Yet although the effect may initially seem alienating, the artist hopes that his work is also an analysis of the film illusion and a means of making us “feel comfortable with the media of our time.”

Sharits’ work will be on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario until March 31. The exhibition includes a retrospective showing of his films, three frozen film frames and an installation piece, entitled Dream Displacements, which requires four separate projectors for the continuous transmission of its frames of bright color and a soundtrack of 75 brandy glasses being smashed on a pane of plate glass, in full quadrophonic. Needless to say, one waits in vain for the opening or closing credits.

The 35-year-old filmmaker, once himself a painter, finds physical properties in this film set-up that neither painting nor conventional film viewing can duplicate. “Film, unlike sculpture or painting, is timebound. With a picture in an art gallery, you can go away and come back again and it will still be there. No one tells you how long to look at it, and you can stand as far from or near to it as you like.”

Most painters cannot control such aspects of the viewing process. But Sharits tells how the Belgian painter James Ensor placed a large organ in his home at a close distance to his famous painting Entry of Christ Into Brussels in 1889, so that visitors were forced to look at it at close range and feel like an extra in the crowd scene.

Sharits feels that the movie theatres also have some of the freedom of a gallery. “In most film theatres,” he says, “you can come and go as you wish, like in a gallery, and you sit up close of far away, and so you lose the sense of the space of the theatre.” But Sharits has deliberately designed his installations to be locational. The projectors are always 18 to 20 feet away, and the quadrophonic speakers outline the boundaries. One feels obliged to view from within that space.

Sharits, who teaches film at the State university of New York at Buffalo, is not just interested in manipulation for its own sake. He wants people to lose their sense of the mystery of film, by exposing the mechanics of it. “Instead of making a documentary on how a shutter works, for example, I want my work to show its effect on the screen.”

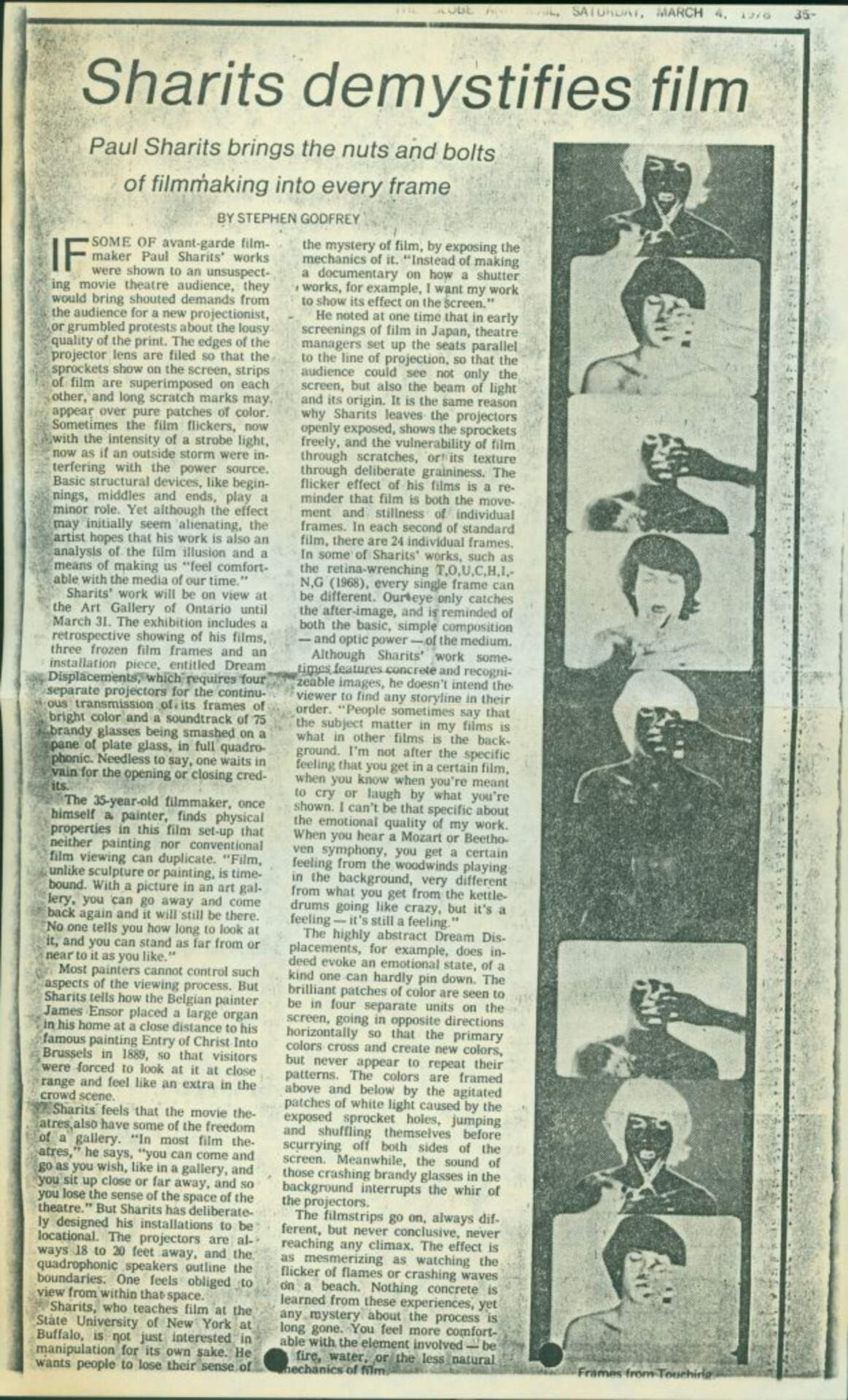

He noted at one time that in early screenings of film in Japan, theatre managers set up the seats parallel to the line of projection, so that the audience could see not only the screen, but also the beam of light and its origin. It is the same reason why Sharits leaves the projectors openly exposed, shows the sprockets freely, and the vulnerability of film through scratches, or its texture through deliberate graininess. The flicker effect of his films is a reminder that film is both the movement and stillness of individual frames. In each second of standard film, there are 24 individual frames. In some of Sharits’ works, such as the retina-wrenching T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968), every single frame can be different. Our eye only catches the after-image, and is reminded of both the basic, simple composition—and optic power—of the medium.

Although Sharits’ work sometimes features concrete and recognizable images, he doesn’t intend the viewer to find any storyline in their order. “People sometimes say that the subject matter in my films is what in other films is the background. I’m not after the specific feeling that you get in a certain film, when you know when you’re meant to cry or laugh by what you’re shown. I can’t be that specific about the emotional quality of my work. When you hear Mozart or Beethoven symphony, you get a certain feeling from the woodwinds playing in the background, very different from what you get from the kettledrums going like crazy, but it’s a feeling—it’s still a feeling.”

The highly abstract Dream Displacements, for example, does indeed evoke an emotional state, of a kind one can hardly pin down. The brilliant patches of color are seen to be in four separate units on the screen, going in opposite directions horizontally so that the primary colors cross and create new colors, but never appear to repeat their patterns. The colors are framed above and below by the agitated patches of white light caused by the exposed sprocket holes, jumping and shuffling themselves before scurrying off both sides of the screen. Meanwhile, the sound of those crashing brandy glasses in the background interrupts the whir of the projectors.

The filmstrips go on, always different, but never conclusive, never reaching any climax. The effect is as mesmerizing as watching the flicker of flames or crashing waves on a beach. Nothing concrete is learned from these experiences, yet any mystery about the process is long gone. You feel more comfortable with the element involved—be it fire, water, or the less natural mechanics of film.