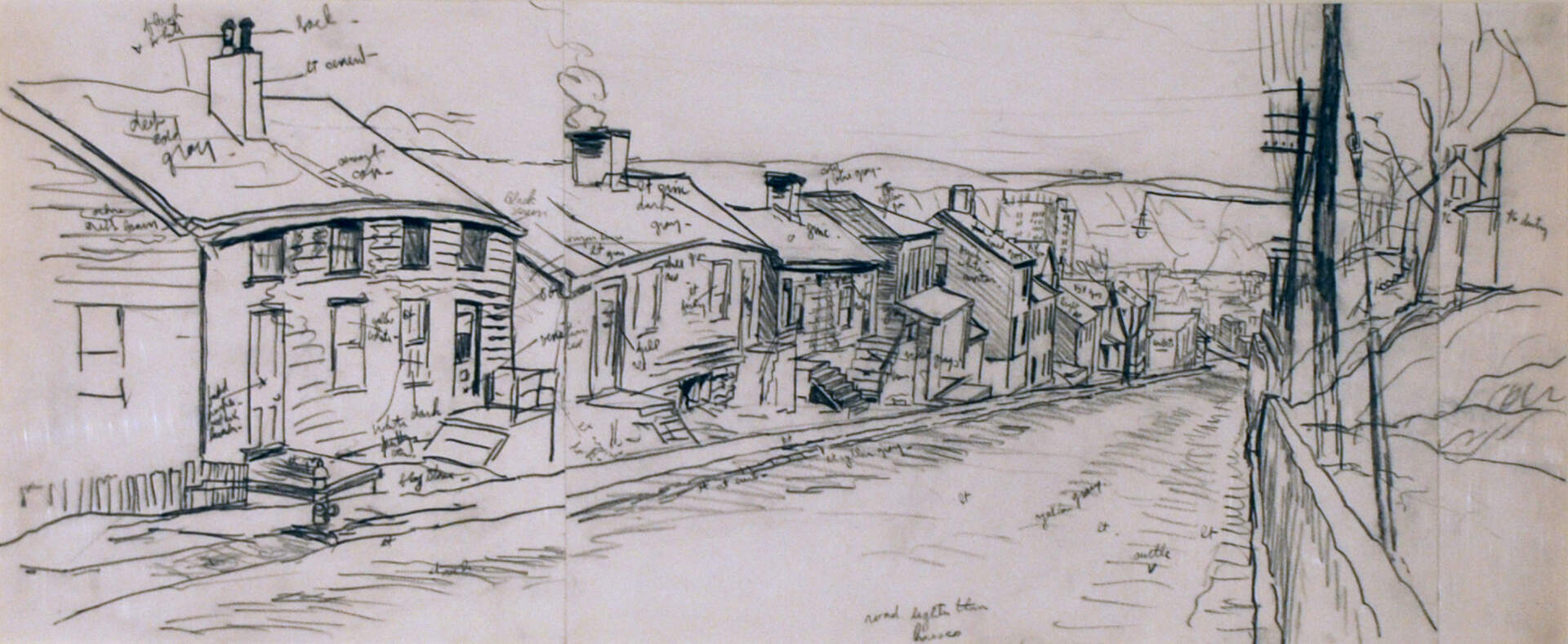

Charles E. Burchfield (1893-1967), Study for End of the Day, c.1936-38; charcoal on paper, 11 7/8 x 28 7/8 inches, Burchfield Penney Art Center, Gift of the Burchfield Foundation, 1975

Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, August 16, 1939

Wednesday, Aug 16, 2023

By now I was growing hungry, and began to look for a hiking hill where I could eat my lunch. I had not gone far on 255 when I came to the village of Byrnedale, which is as fantastic an example of industrial exploration as I have ever seen. I had always felt that Irondale, under a hot August sun, was the last word in desolation, but Byrnedale exceeds it by far. The houses, in grouped rows, in various spots thru the valley, were all alike – crude frame structures, once painted the usual red, which was old and weathered, of a dirty wine color. A great tree-less hill, its sides bare of grass, and revealing the dry pinkish white clay surface, sprawled along the east. At its base was a long row of abandoned coke-ovens, and part-way up its side extended a railroad in the center of the vast tree-less expanse around which the town was built, was a baseball diamond, with a small grand-stand at one end. This one concession to amusement seemed only to accentuate the isolation. The hot sun beating pitilessly down made the valley seem like an inferno – an inferno whose heart is burnt out, leaving a sterile crater.

Secretly I rejoiced that there was still a section of country so near me that was beyond the “blighting” influence of improvement. Or, rather I was torn between conflicting emotions – I pitied the inhabitants, but my artist’s soul rejoiced at what was an artistic perfection in horror.

Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, August 16, 1939