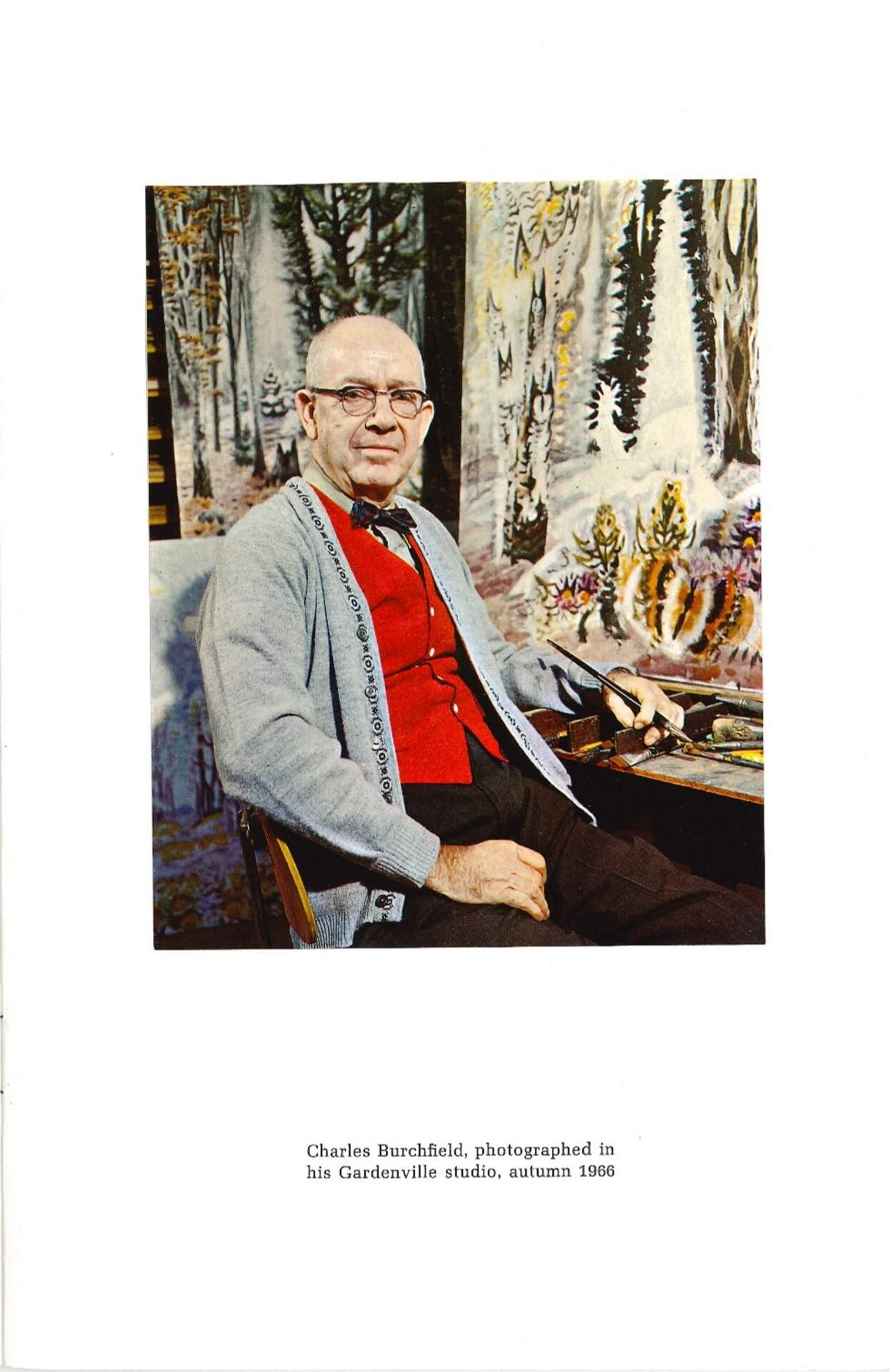

Charles E. Burchfield in his studio, Gardenville, New York, Autumn 1966, photograph by William M. Doran used in the Dedication Catalog for the inauguration of The Charles Burchfield Center, December 9, 1966

Charles E. Burchfield, Dedication Catalog, The Charles Burchfield Center, December 9, 1966

Saturday, Dec 9, 2023

The work of any creative artist is generally divided into three periods, viz.: early, middle, and late, as his art develops or changes. That has been the case in my career, that is, until recently. There is now talk among a few commentators and connoisseurs of a “Fourth Period,” by which is meant the emergence of a semi- or almost complete abstraction. I recognize this myself, but it is an abstraction not to be confused with the “school” which has appropriated the same.

It is rather the conventionalization of nature moods, or formations, into abstract forms or motifs. It was born of a conscious aim, which has existed throughout my career, to reduce painting to its simplest form, trying always to eliminate nonessentials (realistic embroideries) so as to reduce painting to its simplest, even stark, terms without losing the basic idea or reality. If this is done successfully, a realism emerges more genuine than the thing itself.

In my recent work, this tendency has indeed become uppermost, perhaps enough so as to create the illusion of a “Fourth Period.” To me, however, it is the approach to a climax, before mentioned, of the aim that has persisted throughout the years, even in 1916, when I first attempted to paint lightning flashes. The idea of dividing creative work into “periods” does not particularly appeal to me; I do not like to be imprisoned in the idea of adhering to the style of any period. In fact, the artist is, I believe, rarely conscious of transitions from one period to another; they become apparent only in retrospection.

Charles E. Burchfield, Dedication Catalog, The Charles Burchfield Center, December 9, 1966

Artwork on easel: Autumn to Winter (c. 1964-66); artwork behind him: Early Spring, (1966-67) and Hemlock in November (1947-1966)