Fire and water — color, that is — together

Monday, Dec 16, 2013

The Philadelphia-born artist James Queen (1820 or 1821-1886) was known for his printmaking and lithography skills, but he also produced several watercolor works that are just as interesting and intense as his works in other mediums.

Queen began his career as an apprentice to P. S. Duval in the 1830s and created lithographs for magazines, ads and landscapes. Queen not only worked as a commercial artist, but also created artwork inspired by activities and organizations that he himself had an interest in or participated in. For example, Queen served in the Pennsylvania Militia during the Civil War, and his body of work includes several war-themed and military-themed works.

Another example: Queen was a member of the Weccacoe Engine Company, a volunteer fire company in Southern Philadelphia. Thus, his body of work also includes several works that depict mid-1800s firefighters and several certificates, which would be printed, filled out and given to fire company members for their service.

The process of lithography — where the artwork is created on a piece of stone with a grease-like ink, then etched, inked and printed — is capable of producing images with great range and detail. The potential to capture the details of mid-1800s firefighters and their world in lithographs is great; just take a look at the fire scenes created by Currier & Ives, which are full of dark, rich colors and strong lines. But the medium of watercolor, which "Gardner's Art Through the Ages" describes as "transparent, with the white of the paper furnishing the lights," could be a poor choice for showcasing the romantic and often dangerous world of 19th-century firefighting. However, in Queen's capable hands, the medium of watercolor rises to the occasion.

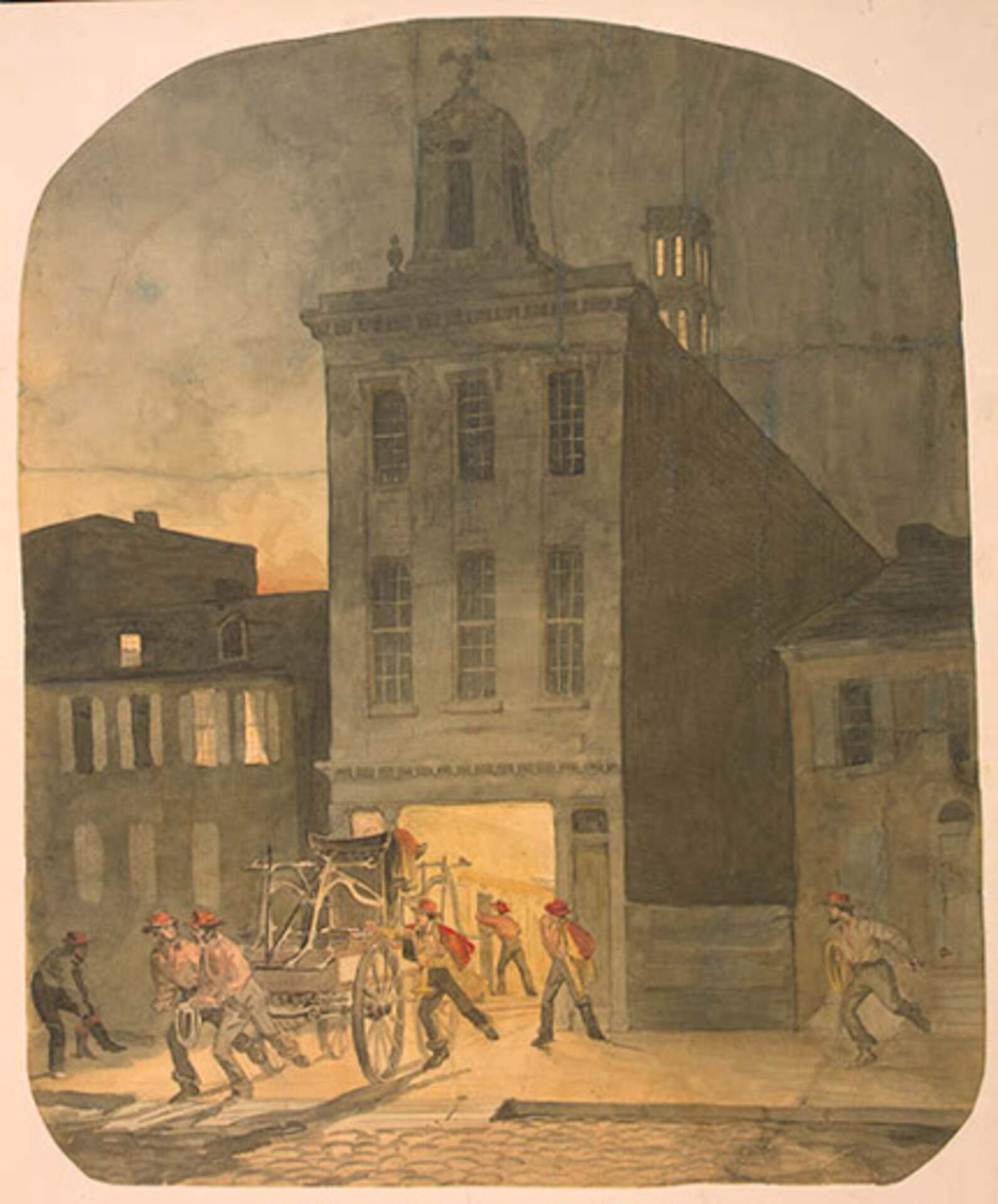

Some of Queen's fire-themed works are in the Library of Congress, which acquired them as part of the Marian S. Carson Collection of early Americana, and can be found on the library's Web site (http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/tri059.html). The two examples there show an educated and sensitive use of light; both works show firefighters running to a call, pulling their fire engines behind them. In the first work (right), light emanates mainly from the firehouse, but it also is evident in the top left side of the watercolor painting. Could it be the blaze the firefighters are racing to meet, or is it something altogether less menacing, such as the sun? If that light in the sky is the fire, then why isn't it portrayed as a bright and intense orange or red? Instead of intense swaths of color, Queen conveys the potential emergency of the scene though other details in the painting: the motion of the firefighters' legs, with some of them off the ground; the shadows they cast, implying their hastened movements; and the outstretched arms of some of the firefighters as they move through the darkened streets. Many of the details of the scene are set in soft focus, too: The cobblestones are indistinct; there is less focus on the firefighters' facial expressions, as some of them aren't very clear; and Queen's only flashes of red are the firefighters' hats and capes. But despite the lack of details and the absence of intense shades of color, a viewer can see that this scene is about responding to a call of potential danger, even if the danger is only hinted at.

In the second work, the time of day is later. The moon casts some light onto the firefighters as they run to their call, and there is some light from the building behind them and the streetlight to their right. There is a lack of intense color and many of the painting's details are in soft focus. Queen uses movement to suggest a pending emergency of some sort. In this work, some of the facial expressions of the firefighters are more discernible. There is intensity and seriousness on their faces, and even an open mouth, perhaps suggesting that the firefighter was yelling, either to alert people or to make sure people moved out of the way so the fire engine could fly past. Here, too, the artist reserves the use of a darker red only for the firefighters' hats, but notice the color that he casts over the majority of the scene — the buildings, the rooftops and even the ground. It's a soft glow with a pinkish tone. Could it be the reason that the firefighters are out at such a late hour? Is it a fire that threatens lives and properties?

Overall, Queen's depictions of early American firefighting in watercolor are notable for their realism and use of light. They convey a sense of the potential danger that these firefighters faced, albeit without as much detail and intense use of color that were common in artwork of the same era.

—Margaret Coghlan

Margaret Coghlan is a first-semester museum studies major at Buffalo State College. She has been a volunteer for more than 20 years and a board member for more than 8 years at the Buffalo Fire Historical Society. She is on the board of Fire Museum Network, a national consortium of fire museums. And she has been going to fires since she was nine months old, when her firefighter dad took her to her first one.

The image is a part of the Marian S. Carson Collection of early Americana acquired by the Library of Congress in 1996. The collection of 10,000-plus items includes dozens of works by Queen, according to the Library of Congress' Web site, "from the late 18th and early 19th centuries" that document "the founding of the nation ... and the development of nearly every realm of American endeavor, from education, religion and technology to industry, science and medicine."