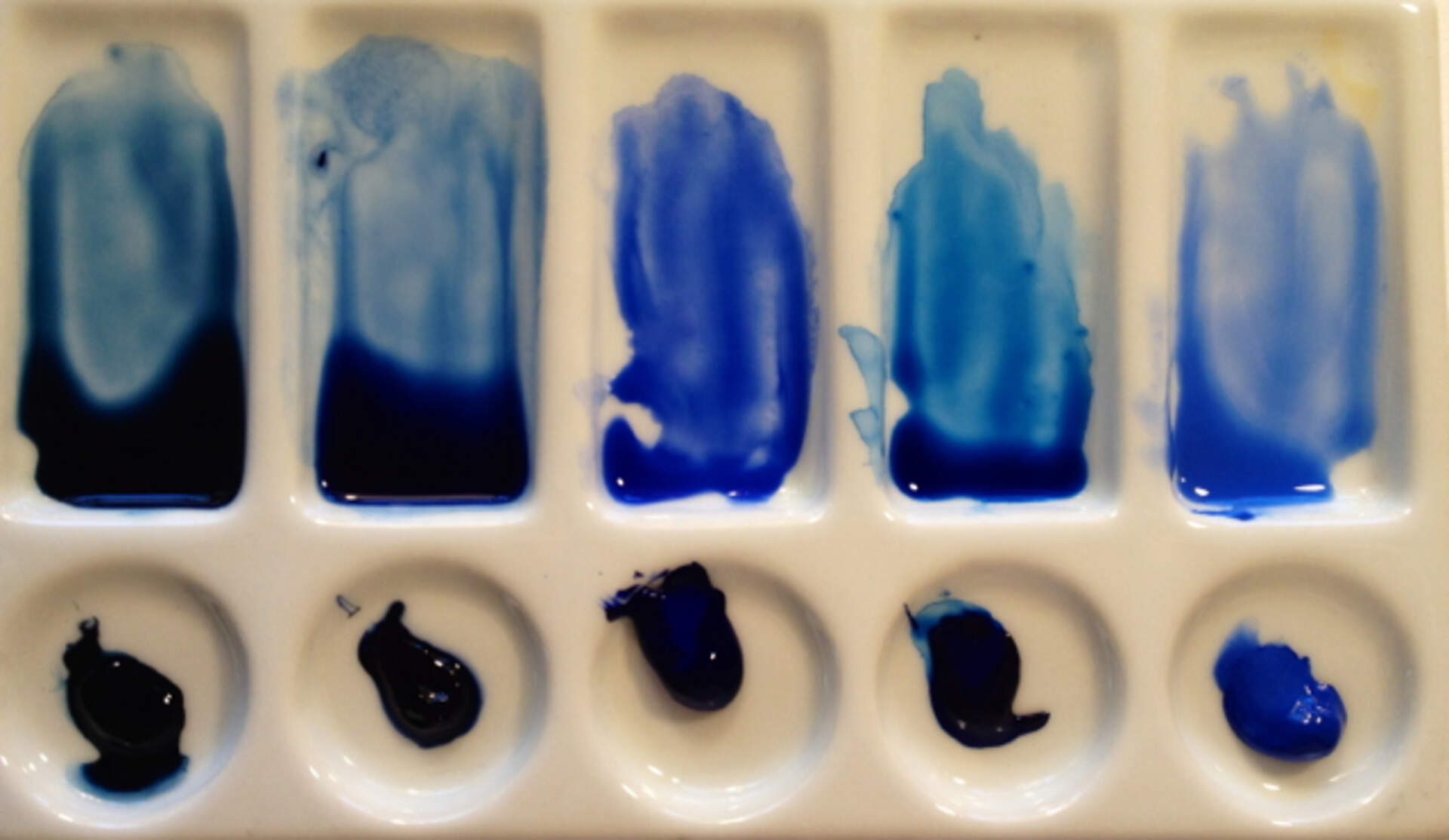

From left to right: Indigo (W&N), Anthraquinone blue (MG), French Ultramarine (W&N), Winsor blue (W&N). and Cobalt blue (W&N).

Thinking About Blue

Friday, Nov 22, 2013

Blue is the canvas on which every other colour rests. On a sunny day it can surround us. From above, a sky is like a cathedral dome of heavenly hue. From the ground, it is reflected by entire oceans and seas, even the smallest streams and ponds. It is Nature’s backdrop for whatever landscape we might find ourselves in, but it is rarely found in trees, flowers, fruits or vegetables. In the manmade world, it is the shade of denim as well as the colour most often used for the garments depicted in religious art—think of the Virgin Mary’s glowing blue mantle. It is the colour of every newborn’s eyes and the most popular shade for items we purchase for our kitchens. Think of stoneware blue, Blue Willow china, the speckled blue tin ware that the pioneers used and that campers still purchase to make food and coffee outdoors. Hospitals use blue for surgical rooms, everything from the gowns and masks of the staff to the sheer plastic packaging for sterile tools, because it suggests purity and cleanliness. When asked for their favourite hue in the rainbow, blue is the colour most people choose. It can portray the cold of winter and the wet of rain, and also the intensity of a hot summer day.

Could blue be the most complex hue in the rainbow? Consider the mystery of the deepest midnight blue, the authority and conservativeness of navy blue, the bright sparkle of happiness of the clearest middle shades, to the purity and serenity of the palest, barely blue tones. But what about singing the blues or feeling blue? In English, the idiom “to feel blue” has no equivalent in other languages, and yet in German “blau sein” (to be blue) means to be drunk. “Голубой,” or goluboy, the Russian word for light blue, is slang for the word homosexual; and, in Belgium, light blue is the colour for baby girls, while pink is associated with baby boys. In Korea, instead of black, a pale blue represents the colour of mourning, and in China the shades of blue are described as shallow or deep instead of light or dark, likening it to the colours created by the depths of water. In the Hindu religion, the god Krishna has blue skin, and in Italy and Spain a fairy tale prince is called the Blue Prince instead of Prince Charming. If the colour blue was removed from the spectrum and from our vocabulary, what colour would fill the void? How would we see or describe the sky and the sea? Without blue we would not have green. Complicated colour, indeed.

In my Roget’s thesaurus there are thirty-six synonyms for the adjective “blueness,” words such as slate, aqua, peacock, kingfisher, cobalt, cyan, cerulean, sapphire, ultramarine, French-blue, hyacinth, midnight, navy, indigo and azure. As an artist, these words are familiar to me. Blue is a colour I work with, and contemplate, every single day. Paint companies offer hundreds of possibilities, but in reality there are only seven blue pigments used in the manufacturing of modern, artist-quality paints. The marketing of art materials is brim with romance though, trying to sell you twenty different shades of blue, when in truth you might be getting the same pigment in different strength, and with different names, many of which come straight from Roget’s.

The blue pigment scale is defined by the letters PG and followed by a number; the most commonly used are pthalocyanine (PB15), iron or Prussian (PB27), cobalt (PB28), ultramarine (PB29), manganese (PB33), cerulean (PB36), and indanthrone (PB60). Seven blues. From these seven pigments, the Winsor & Newton brand offers nineteen blues to the watercolourist, and M. Graham offers twelve varieties, all tints of the core seven pigments. There are as many approaches to palette choices as there are individual artists, but for an artist on a budget, or who simply wants to keep to a limited range of colours, even seven might be too many. So why all of these blues? Marketing romance equals more sales.

Throughout history, blue pigments have been difficult to come by and expensive to produce. The colour didn’t make an appearance in art until the Middle Ages, and up until the mid-eighteenth century the only raw pigment of blue was obtained from the semiprecious stone, lapis lazuli, at that time found only in caves in Afghanistan. Because it was costly and hard to transform into paint, it became a colour associated with the elite (it was used for the eyebrows on the funeral mask of King Tutankhamun), a symbol of power and wealth. In paintings from this time period, if the garments worn by the subject were blue, chances are they were considered royalty, blessed, or very important. During the Renaissance, blue was almost always reserved for depicting the robes of angels or the Virgin Mary. In true revolutionary form, the common folk wanted their own access to blue, not only to paint with, but to dye their cloth and tint their pottery. Eventually the pigment Prussian blue was discovered in the late 1700s. It was useful and affordable to many, but still did not match the pure blueness or brilliance of lapis. In 1826, ultramarine was discovered by a French scientist, Jean Baptiste Guimet, as a synthetic replacement for lapis. It is the closest pigment (still today) we have to the costly, pure lapis lazuli. More pigments were discovered and manufactured throughout the following centuries, the latest of which are the pthalocyanine family of pigments, the brightest and most transparent of all blues available to the twenty-first century artist. Perhaps the fact that pure blue pigments were so precious and hard to come by is reason enough to offer such a wealth of choices today.

I have experimented with every blue available to me as a watercolour artist and I’ve narrowed it down to only four on my palette: French ultramarine for its unrivalled ability to mix brilliant purples, and its beautiful granularity that provides subtle texture to washes; Indanthrone for its transparency and smoothness—contrast to the coarser ultramarine—and for its earthier hue that lends to the more muted tones in natural history illustration; Prussian blue for its ability to create the deepest darks and, because it leans toward the greener side of blue—it is ideal for creating turquoise; and cerulean blue for its opacity and assertive texture that can allow the artist to create radiant drama in skies. If I were to add one more blue to my palette it would be cobalt. It is easily replaced by ultramarine, but is still unique with a clearness and intensity of colour that will last forever, and that accents the finish of the paper like no other blue. It is fascinating to discover just how many tones and textures can be created with only a handful of blues, each irreplaceable. No colour other than blue offers such challenge and reward as I learn how best to work with it.

You don’t have to be an artist to pay closer attention to how colour shapes the world around us, or how it affects our thoughts or moods. Do we take colour for granted in our everyday lives? When is the last time you sat and pondered the way the rainbow inhabits everything you see or do? Have you stopped to consider how many shades of brown and grey are captured in a stand of naked trees or how snow is really every colour but white? As a watercolourist I now see everything in terms of not only shape, but colour, and no colour is as elusive or as important to me as the colour blue.

Forget gold; for me, blue is the treasure of the rainbow. If grey is the colour of truth, then truth is cloaked in blue. Look around you. I bet there are a hundred of shades within your reach.

—Kateri Ewing

Kateri Ewing is a writer and self-taught watercolourist from East Aurora, New York. The fields, ponds and woodlands of her beloved Knox Farm State Park are her place of inspiration. She hopes to reveal the intricate details of the cycles of nature, the luminous particulars she notices in natural objects, such as a single seedhead of grass, broken acorn, decaying leaf, or the spirit of a tiny nuthatch spiraling down a hemlock tree. The birds of Western New York have become her favorite subject to capture on paper, as she aspires to portray each one in a way that reveals its uniqueness, right down to the spark of life in its eye. It is the desire to urge others to pause, and look a bit more closely, that stokes her creative fire in both writing and visual art. Visit her online portfolio at www.kateriewing.com