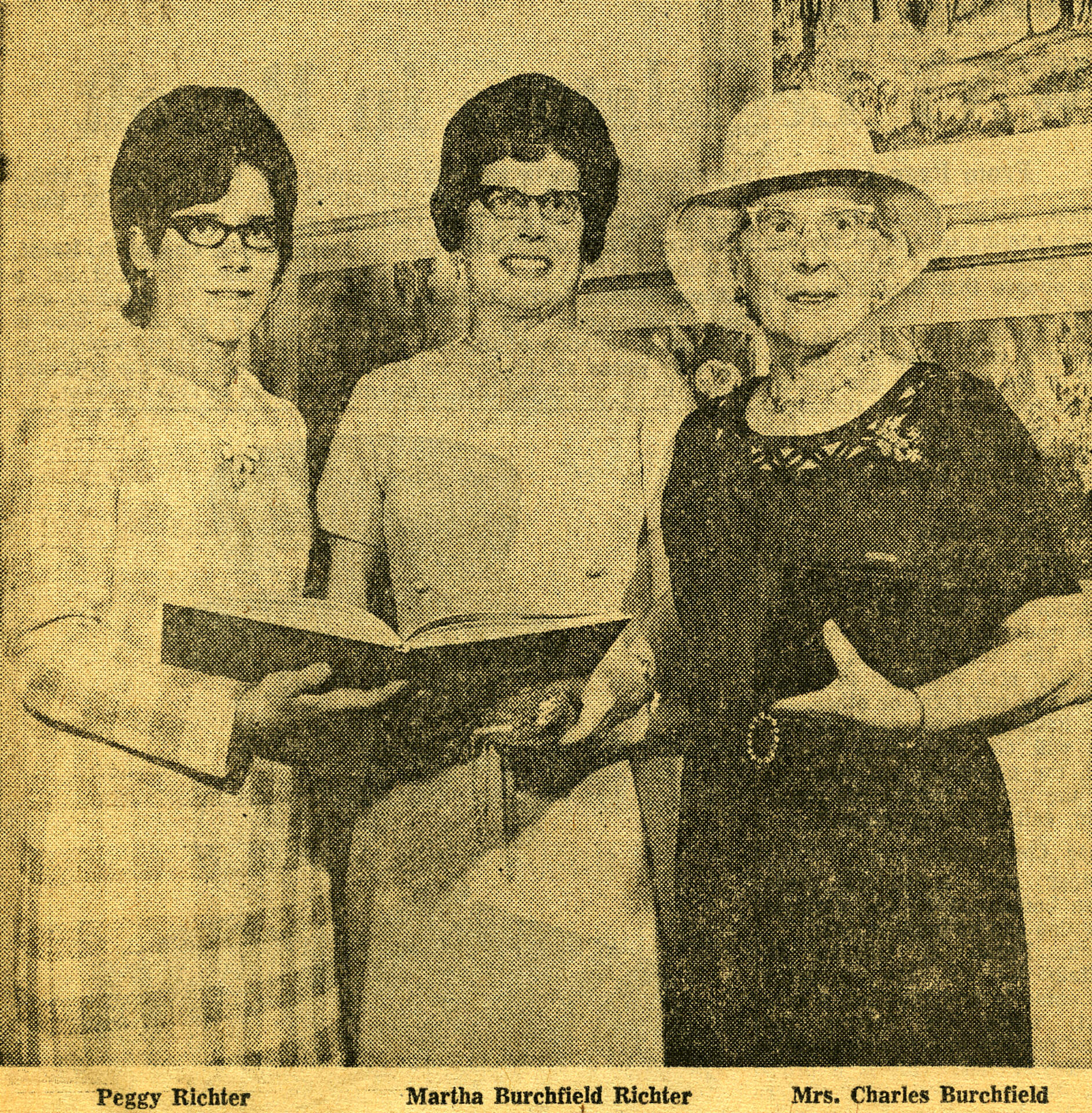

Buffalo Courier-Express, Photograph of Peggy Richter, Martha Burchfield Richter, and Mrs. Charles Burchfield, c.1968; newsprint; Image courtesy of Burchfield Penney Art Center Archives

Burchfield Family Visit

Wednesday, Sep 21, 2016

On Saturday, September 17, 2016, I had the distinct pleasure of touring Charles Burchfield’s granddaughter Peggy Richter Haug, her daughter Kirsten Haug, and Peggy’s brother David Richter through the museum. Peggy, who lives in Washington State, had only been to the new building once before, for the opening of Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield in 2010. David, who lives in Toronto, had only been here twice, but it was Kirsten’s first visit. To say that they were impressed, and proud of being associated with our founding artist, is putting it mildly. They were elated, stopping at every single artwork, from small study to grand masterwork, to marvel at his genius.

It’s fun to see what memories get sparked when people visit the Burchfield Penney Art Center. One of David’s first recollections on entering the museum was his grandfather’s way of flicking his fingernails on his thumb. Burchfield, no doubt, would have loved this recollection, especially since he valued childhood memory as a major catalyst for recurring ideas in many of his artworks.

After I told them about Gwathmey Siegel and Associates Architects and their design concepts for the building, we stopped at the Store, where I pointed out how Burchfield’s doodles had been enlarged for the walls. They loved how such a small detail became a design element.

Next door, David Moog was in his studio, so I introduced him to them. Peggy, who is an artist, will return to have her portrait photograph taken, and David Richter, who is a concert pianist and noticed that Brahms was playing in the background, said he would come back another time to participate in Artists Seen: Photographs of Artists in the Twenty-first Century: A Project by David Moog. Moog is attempting to make black & white portraits of all the working artists in, or associated with, Western New York. Painters, printmakers, sculptors, wood workers, potters, craftspeople, photographers, installation and performance artists, musicians, curators, and gallery owners will be included. Documenting these Burchfield family members is a priority!

Next we went to the Collection Study Gallery, where they looked at sketches and studies associated with Mystic North: Burchfield, Sibelius, & Nature and talked about Burchfield’s relationship to music. Peg marveled over the notes on sketches, and the forms themselves, such as The Spirit of Winter lurking in a woods and 3 of 58 Studies for In the Deep Woods, especially the animated depiction of Pink Lady’s Slippers. I spoke about how I thought Burchfield was synesthetic, even though he wouldn’t have been familiar with the term. His relationship to music and the ways he represented it visually is quite unique.

They looked at every work in Blistering Vision: Charles E. Burchfield’s Sublime Landscapes. (Unfortunately, Tullis Johnson, who had curated the exhibition, was out of town and could not join us.) From the very first work, Sunburst, they were thrilled to see how differently the paintings looked in person. This oil had not seemed as grand in reproductions. Now they saw how Burchfield’s subtle variations in green and gray were developed. They spent a lot of time at Cattaraugus Canyon (March Canyon) on the title wall, talking about their many hikes in Cattaraugus Canyon/Zoar Valley. They discussed the painting’s perspective point and agreed that the distant bluff was where they would look out on the vista. Peg thought the fire in the distance might be from farmers burning old crops to get the land ready for new planting, rather than a forest fire or swamp fire. I told them the story of Niagara Mohawk’s plan to build a dam and flood the canyon that was abandoned, the sale of land to the Darling family, and the eventual discovery of an American Chestnut tree by Herbert Darling Jr., who created the American Chestnut Society (relating to Summer Solstice (In Memory of the American Chestnut Tree), which was presented at the beginning of the exhibition in reproduction and with studies. They also loved the painting March Sunlight, which more closely captured the view they remember, and were thrilled to see the study of Martin’s Point, which they recognized as the name of their favorite lookout spot.

They literally marveled over every aspect—art and archival documentation—and Kirsten took many photographs of their discoveries. The Gardenville Studio evocation really brought back lots of memories. David asked if we were aware there had been a pull-down ladder in the ceiling near the skylight. The Richter family lived nearby, so they had frequently visited their grandparents, and Peggy lived with her grandmother, Bertha, for three years after Charles passed away on January 10, 1967.

The exhibition contained so many works that they had never seen before, as well as items related to aspects of Charles Burchfield’s work, such as illustrations for Fortune magazine, that they had not known he had done. They were interested in his process, particularly on his method of adding paper for his composite paintings. Peg asked what kind of paper he used. I told them about Whatman watercolor paper, and the story about “Bee Hepaticas” and our discovery of the studies for The Fragrance of Spring and the realization that the working title referred to Bee brand watercolor paper. (I will send her information about Burchfield’s papers that I have researched, as well as excerpts from the article co-written with paper conservator Patricia D. Hamm.)

In the last section of the exhibition, they were particularly taken by The Four Seasons and Early Spring. Based on an exhibited study, they were impressed that “Eye of God” in Woods is owned and exhibited by the Vatican.

We also looked at some of the artwork in the museum’s collection that is not currently on exhibition. Peggy is an artist herself, following in her grandfather’s and mother’s footsteps. Upon being shown her own painting, Oriental Poppies, which Charles Rand Penney had donated in 1991, she recalled how in 1969 she and her mother, Martha Richter, had gone on a rare painting expedition together and both painted this scene. Peggy was closer, so her poppies dominated the painting; while Martha’s rendition was from a farther perspective. Just like that painting excursion, this cross-country trip brought family together—mother and daughter with brother/uncle—to make a meaningful museum experience where art and memories and new observations united.

Nancy Weekly

Burchfield Scholar