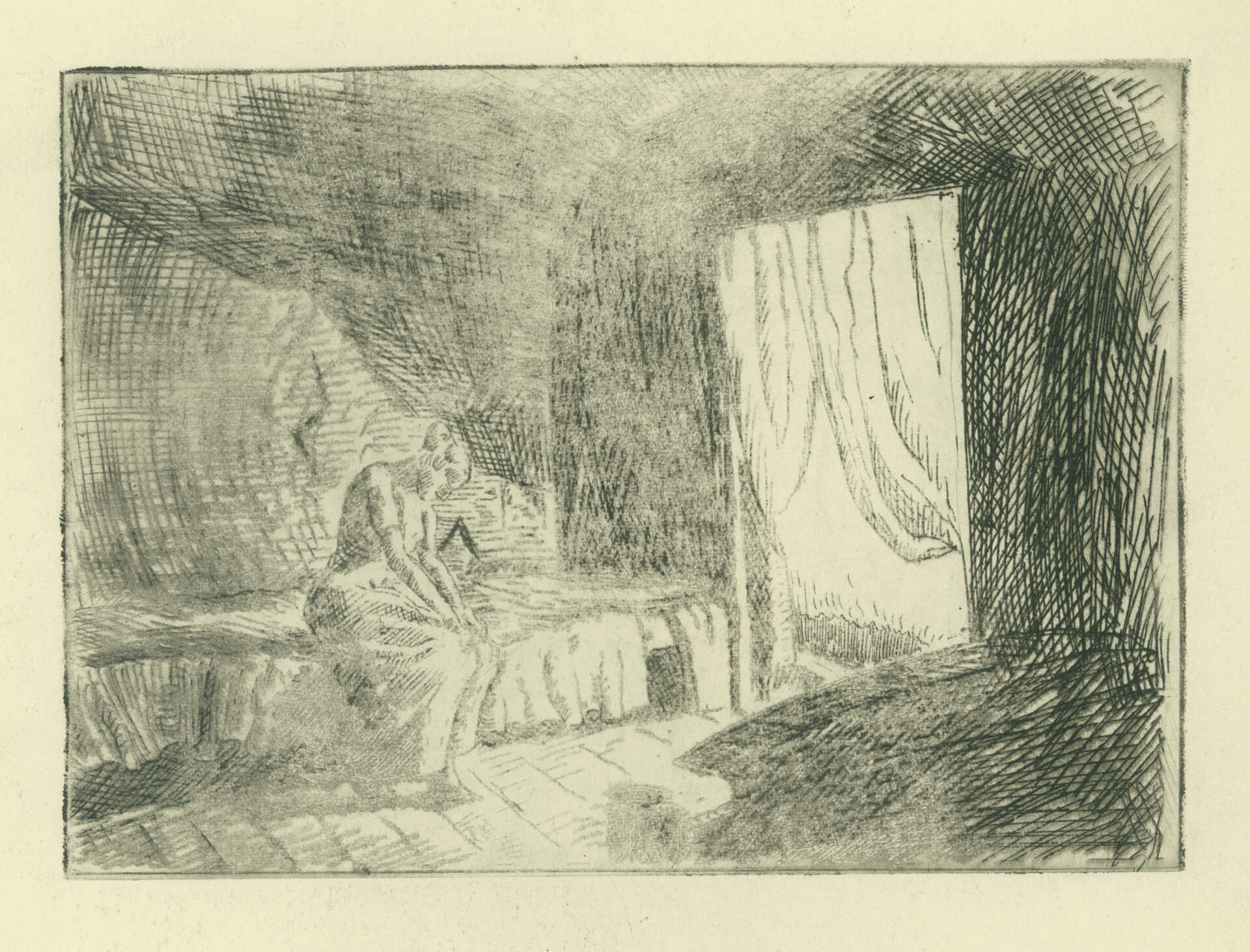

Charles E. Burchfield (1893-1967), Dejection, 1919; intaglio on paper; trial proof probably printed by Frank N. Wilcox (1867-1939), 5 x 6 7/8 inches (plate), 14 x 10 (sheet); Burchfield Penney Art Center, Gift of the Charles E. Burchfield Foundation, 2006

Burchfield Joins Hopper Overseas

Tuesday, Sep 11, 2012

Recently NPR aired a story by Susan Stamberg about a painting by Edward Hopper traveling abroad. Stamberg interviewed staff at the Columbus Museum of Art about their loan of Edward Hopper’s oil painting, Morning Sun (1952). (See “Pensive Lady in Pink Travels the World,” NPR, August 20, 2012: http://www.npr.org/2012/08/20/157104327/hoppers-pensive-lady-in-pink-travels-the-world.) Morning Sun features a young woman sitting on a bed, staring out a window, lost in thought. The air feels still, even stifling, in this very moody scene. She is not smiling, so we wonder with what trepidation she is pondering the new day.

Morning Sun is currently on view, not in Ohio, but in Madrid, Spain, where it is part of the significant retrospective Edward Hopper (1882-1967), a traveling exhibition that includes five works by Charles E. Burchfield: Corner House, Gray House, Moonset over the Railroad, Promenade, and Orion and the Moon. The exhibition premiered at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza (12 June – 16 September 2012) and then it goes to the Réunion des Musées Nationaux in Paris, France (5 October 2012-28 January 2013).

Sally Fehskens, the Burchfield Penney’s curatorial assistant in archives, saw the exhibition in Spain, so she is going to tell us about her wonderful experience in an upcoming blog. I am writing to say a few words to point out the importance of Burchfield contextualizing Hopper, who was eleven years his senior. They were friends through the Frank K. M. Rehn Galleries—which represented both artists in New York. They wrote about each other’s work and subtly competed with one another while enjoying equal praise and recognition during their careers. There are similarities as well as differences in their art. Burchfield did not often depict people in his landscapes, choosing instead to work more symbolically—for example, making trees or houses reflect human characteristics. Yet Morning Sun deserves comparison.

Few people are aware that in 1919 Charles Burchfield created zinc etchings that were printed with help of his Cleveland School of Art colleague Frank N. Wilcox. His etching titled Dejection, like Morning Sun, also depicts a young woman sitting on a bed in a brooding composition. While some of Burchfield’s etching subjects were based on caricatures of local inhabitants, others may have been modeled after Sherwood Anderson’s psychologically burdened characters in Winesburg, Ohio, which Burchfield had read shortly after it was published in 1919. In Dejection a woman is perched on a bed in an oppressively darkened room. Her head is bent low and her hands tightly clasp her knees. Both the image and the title signal that she is absorbed in despondent thoughts, oblivious to the promise of a brighter future represented by a backlit, curtained window. This foray into figurative subject matter and dramatic structure might be compared to Edvard Munch’s 1894 lithograph, The Young Model (Puberty), portraying a sexually uncertain adolescent girl seated naked on a bed, hands crossed at her knees, melded to the ghoulish shape of her own towering black shadow; or Munch’s 1894 drypoint and aquatint print, Compassion, in which the same nude young woman, hands held to her distraught face, is comforted by the embrace of a nude male youth. Burchfield lists several subjects of his etchings as “imaginary,” yet they each convey, whether consciously or unconsciously, the fluctuating melancholy and joy of his own experience. In 1919 he was back at home after an honorable discharge from the U.S. Army, still unattached at the age of 26, future uncertain, but rejuvenated by the unchanging countryside and old routines. Not uncommonly, restlessness and a seemingly fallow period precede significant change for an artist—and Burchfield’s successful painting career was yet to blossom on a national scale.

Nancy Weekly

Head of Collections and the Charles Cary Rumsey Curator