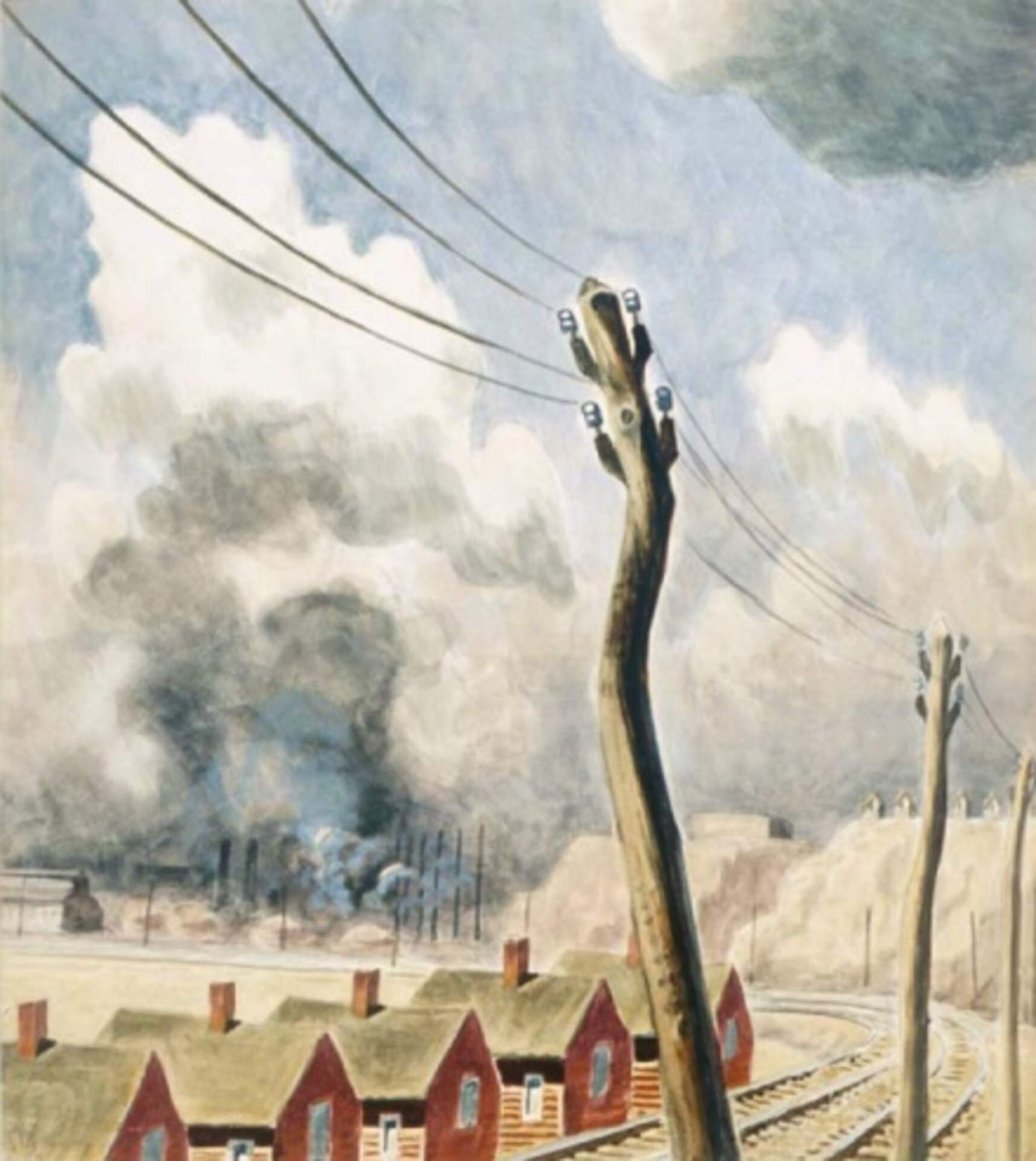

Charles E. Burchfield (1893-1967), Telegraph Pole, 1935; watercolor, charcoal and graphite on paper, 23 3/8 x 20 7/8 inches; Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, Gift of Mrs. Charles H. Babcock

Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, August 16, 1939

Tuesday, Aug 16, 2016

Up at about eight o’clock. A heavy bank of white mist hovered low over the town, which, tho it obscured actual sunlight, permitted enough light to seep thru to create a sort of luminous twilight that was very strange. After breakfast, I strolled around the town, enjoying the atmosphere, and making a few studies.

It was nearing noon when I finally started out with the car. I headed for the Driftwood section, thinking I might still get the locomotive and hill sketch I had come for, tho I knew in my heart that I was going to do otherwise, for I was tired, and besides had a desire to explore the country below St. Mary’s.

After getting sandwiches, and gas etc. at the station below Driftwood, I took route 555 south from Driftwood, lighthearted because I, by so doing, admitted openly to myself that I was going to loaf today, look for new material, and eventually go home.

Route 555, mostly what is termed “improved” dirt road (tho some of it was under construction) proved to go thru a most wild and desolate section of country. For miles the only human touch would be, besides the road, the single track railroad running alongside. Mile after mile of great tree-covered hills, without a house or sign of habitation. A sulphur stream ran thru the valley, and being shrunken by the dry weather, revealed the rocky bed, heavily encrusted with sulphurous or iron sediment, - a brilliant orange in color, unbearable in its intensity. It had a ghostly, almost frightening appearance.

The heat was terrific; it came into the car in waves off of the road – the hills seemed to writhe and quiver as paper will on a red-hot stove.

I went thru several forlorn villages, and eventually after coming into more open country, arrived at Weedville, where a man directed me to route 255 to St. Mary’s; which he referred to with unmistakable pride in his voice, as the “million-dollar” high-way, so proud we are, of things that costly.

Expensive or not, the road was a car-driver’s-joy- smooth cement road, so perfectly graded that it seems unnecessary almost to even put one’s hands on the wheel. Driving then becomes entirely automatic.

By now I was growing hungry, and began to look for a hiking hill where I could eat my lunch. I had not gone far on 255 when I came to the village of Byrnedale, which is as fantastic an example of industrial exploration as I have ever seen. I had always felt that Irondale, under a hot August sun, was the last word in desolation, but Byrnedale exceeds it by far. The houses, in grouped rows, in various spots thru the valley, were all alike – crude frame structures, once painted the usual red, which was old and weathered, of a dirty wine color. A great tree-less hill, its sides bare of grass, and revealing the dry pinkish white clay surface, sprawled along the east. At its base was a long row of abandoned coke-ovens, and part-way up its side extended a railroad in the center of the vast tree-less expanse around which the town was built, was a baseball diamond, with a small grand-stand at one end. This one concession to amusement seemed only to accentuate the isolation. The hot sun beating pitilessly down made the valley seem like an inferno – an inferno whose heart is burnt out, leaving a sterile crater.

Secretly I rejoiced that there was still a section of country so near me that was beyond the “blighting” influence of improvement. Or, rather I was torn between conflicting emotions – I pitied the inhabitants, but my artist’s soul rejoiced at what was an artistic perfection in horror.

Charles E. Burchfield, August 16, 1939