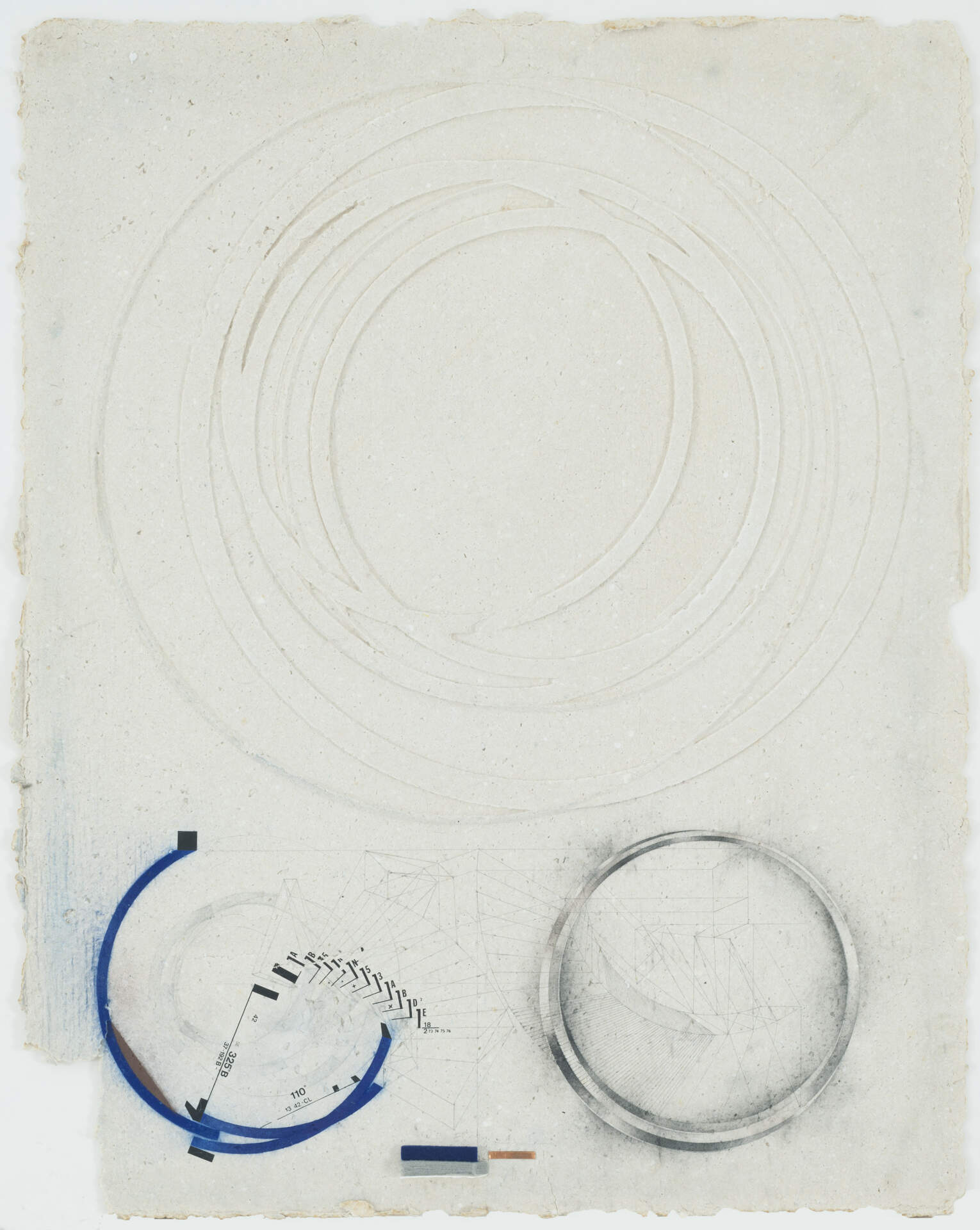

Andrew Topolski (1952-2008 ), Untitled, c. 1998; graphite and mixed media on handmade paper, 62 x 29 inches; Estate of Andrew Topolski

Colin Dabkowski on Enjambment: Andrew Topolski in the Buffalo News

Thursday, Aug 15, 2013

Art, music and architecture harmonize in Andrew Topolski’s work at Burchfield Penney: A friend gathers Topolski’s best work at Burchfield Penney

by Colin Dabkowski in The Buffalo News' Gusto. Read more at www.BuffaloNews.com.

There is an abstract painting by Moira Jane Dryer in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery collection that features a riot of streaked green acrylic paint punctuated by several black dots.

The painting is alluring enough on its own, but what really makes the piece resonate is a metal music stand positioned just to its left. It suggests something strange and central about the intersection of visual art and music, making the viewer wonder if the painting is somehow meant to be “played” on some imaginary instrument.

This idea – that music and drawing, architecture and engineering share some central DNA – is one of the most intriguing aspects of Andrew Topolski’s work, a fascinating collection on view in the Burchfield Penney Art Center through Sept. 8.

Topolski’s work is not nearly as literal (some might say obvious) as Dryer’s, nor does he make the connections inherent in his mixed media pieces especially easy to draw. “My work has not been readily accepted,” the artist once said, “and that is a fact which I find comforting.”

“Enjambment: Andrew Topolski” was curated by Don Metz, a curator at the Burchfield Penney and longtime friend before Topolski’s death at 55 in 2008. It contains several bodies of work from across Topolski’s career as a prolific and gifted draftsman, sculptor and thinker – each of which blends elements of music and architecture with various modes of visual art-making.

We’re greeted with Topolski’s ambitious and beautifully rendered floor design plans for the Buffalo Niagara International Airport, which were passed over for a tamer concept by Robert Calvo. Topolski’s meticulously plotted designs incorporated the solar system and the geography and topography of Western New York into the floor tiles, with a representation of Lake Erie at one end of the concourse and Lake Ontario on the other.

That theme – of combining his fascination with the order of the cosmos with more earthly concerns – continues through the exhibition. Many of Topolski’s untitled mixed media works combine schematic-like drawings with bits of lifted text or photographs, many of them floating underneath a drawn or embossed rendering of what might be a solar system or an atomic diagram.

It’s clear from almost all of his constructions that Topolski was trying to tweeze out some common threads in the grand design. His works – whether they combine maps with music, color theory with architecture or industrial design with abstract drawing – are about seeking the elusive harmonies that connect these seemingly disparate forms.

Such connections might only be imaginary, but that seems beside the point for Topolski. His work was about the search for those common threads, and the search can often be more beautiful than what is eventually discovered. As former News Art Critic Richard Huntington once put it: “You may dig, but you probably will not find.”

In one piece at the start of the show, for instance, the artist meticulously cut out thin strips of a map and pasted them onto the empty staffs of a blank sheet of music paper, as if it could be performed by some impossible orchestra. Of course it can’t, and even if someone figures out a way to make that happen, it might not be discernible from random noise. The idea, like putting a Jackson Pollock painting on a record player, seems infinitely more interesting than its execution.

Topolski’s most visually arresting and successful works, from the ’90s, are literally designed to double as pieces of visual art and musical scores that he performed. These large, black-and-white abstractions feature what looks like a piano keyboard twisted into a circular shape, which Topolski augmented with bits and pieces of indecipherable textual flotsam.

After 9/11, according to Metz’s text, Topolski stopped making art for two years, unable to confront the implications of the attacks. When he finally started again, his pictures seemed even more confusing, even more obfuscated by layers of complexity.

The Topolski we see in this show is an artist always trying to reconcile things that may very well have been irreconcilable. In the wake of the worst terrorist attack in America’s history, that challenge became at once even more difficult for Topolski and more important for his audience.

He seemed to be entering a new and darker trajectory in the last few years of his life. While it’s a shame we’ll never know where it might have led him, this show provides an excellent opportunity to explore and celebrate his singular work.