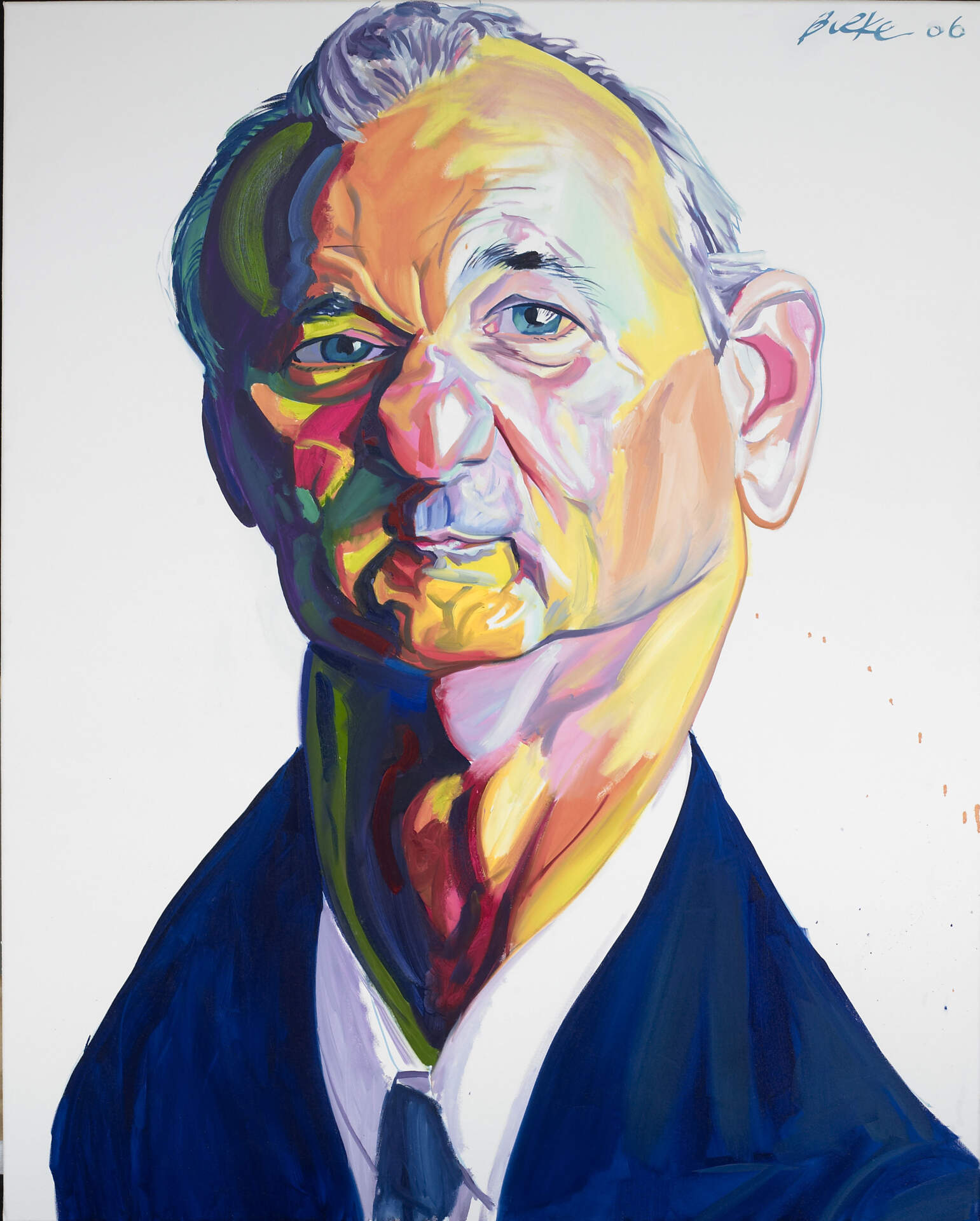

Philip Burke (b. 1956), Bill Murray; image courtesy of the artist

The old razzle dazzle: Philip Burke at the BPAC in Buffalo Spree

Monday, Jul 13, 2015

Read more at www.BuffaloSpree.com.

Hey, isn’t that Tom Cruise sporting a beard over there? And look, there’s LeBron James. Oooh, Dick Cheney looks so nasty! And of course Jerry Garcia looks trippy—but why is he hanging with Conan O’Brian?

You’ll find a veritable who’s who of celebrity sightings at the Burchfield-Penney Art Center (BPAC) these days, courtesy of The Likeness of Being: Portraits by Philip Burke. Burke is a Western New Yorker who has built an impressive career as an extraordinarily successful illustrator. His work has graced the covers and pages of Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, GQ, the New York Times, Newsweek, and many others. His success is based on the one thing he does with unwavering consistency: make colorfully painted caricatures of famous people. And he is extremely good at it.

In his early career, Burke, like many caricaturists, did relatively small ink on paper drawings. A few of these, along with some charcoal renderings, are on view in the current exhibition. Though never formerly trained as an artist, Burke had a natural flair for expressive portraiture early on. But what Burke is best known for, and what makes up the lion’s share of the current extensive exhibition, are large scale oil-on-canvas celebrity portraits. Most are vertically oriented and between three and five feet tall.

Burke knows his way around a brush and palette. He paints straight to the canvas without preparatory drawing, each sweeping brushstroke seemingly accomplished in one fell swoop without corrections or over-painting. He lays down barely-there washes, accompanied by energetic flourishes of thicker paint, punctuated with the occasional expressionistic gob. The result is a sketchy, almost dashed-off effect.

His color palette is bold and idiosyncratic, leaning heavily toward clashing hues that vividly reproduce on the printed page. The majority of the figures are set against sterile primed canvas, a concession to their ultimate role as floating images in white magazine layouts. Blank canvas also pokes through whenever a figure calls for white. Much of the brushwork is done with a light touch and an economy of detail. Frank Zappa’s shirt, for instance, is flat red with a few added painterly slashes. It’s a spare approach that merges watercolor transparency with impasto density.

Some of the figures—James Dean, for instance—verge on straight portraiture. Others, like Little Richard, resemble something out of a Ren & Stimpy cartoon. The painting style sometimes verges on cubism; other times it’s more like German Expressionism—Ernst Ludwig Kirchner on Red Bull. Throughout, Burke favors certain recurring tropes: misaligned eyes, funhouse mirror distortions, shortened foreheads (a young Ani DiFranco comes off looking like a circus pinhead).

The exhibition is grouped roughly into thematic sections: politics, sports, music, and movie stars. Some of the works have never been published, but the majority of the subject matter have been dictated by the demands of the articles they illustrate. Few of the figures offer any contextual information. There are exceptions—a rock star may hold a guitar; Governor Chris Christie is framed by the George Washington Bridge; Hunter S. Thompson is smoking—but a good number are just floating in space. A sixties-era Rat Pack illustration is a standout, with Frank and the boys looking suitably hip. Works with multiple figures provide a rare break from the formulaic structure of the others.

As accomplished as Burke is at what he does, the question arises, just what is that exactly? There is a showcase in the exhibition with examples of his illustrations as they appear in a variety of publications. That’s where it hits you; these works were painted with the specific intent of being shrunk down and printed on glossy magazine paper. As a result, they work much better as small, flattened images on the page than they do as large paintings.

One young woman I spoke to said the fun of the show is seeing the originals of images she grew up looking at in the pages of Rolling Stone. No question, there’s amusement to be had here. But when the fun factor of celebrity recognition dissipates, what’s missing is that je ne sais quoi that endows art with lasting appeal. Burke’s deft spot-on characterizations are clever, but fine art demands more. As paintings, it’s unlikely they would warrant much interest if the subjects were not public figures. Yet, adding intellectual or emotional content, or refining his paint handling to create a more sophisticated surface, would be counterproductive to Burke’s purpose as an illustrator. These images are meant to be viewed fleetingly, six inches tall, surrounded by text; that’s how they function best.

Occasionally, illustrations stand on their own as art, but most often it’s the writing they are supporting that provides the content. Removed from this context, Burke is doing essentially the same thing caricature sketch artists at Darien Lake do—capturing cartoony likenesses of people. There are fine artists who have been known and widely regarded for their caricature work, most notably Honoré Daumier. But Daumier was a satirist whose drawings and prints stand on their own as comments on social and political life in France in the nineteenth century.

Burke’s illustrations are more akin to advertising jingles. Great jingle writers like Randy Newman, Richard Adler, and Jake Holmes are skilled composers who create masterfully crafted earworms that work their way into our collective psyches. Fifty years later I’m still haunted by Kauffman’s Rye Bread’s jolly little baker, and I continue to wonder where the yellow went every time I brush with Pepsodent. But jingles serve a specific commercial function, and no one mistakes them for high art.

There are hints that Burke pursues painting apart from his illustration. One wall of more personal works inexplicably includes an uncharacteristic landscape titled Temple Pond. It looks a bit like a van Gogh, and it might be good. To see it, bring binoculars; the BPAC continues its installation practice of nineteenth-century salon style hanging in which works are crowded together and occasionally stacked to the stratosphere. Craning your neck to see Temple Pond high up on the wall is an unpleasant and unrewarding experience.

The number of works in The Likeness of Being: Portraits by Philip Burke could be cut by half and still comfortably fill the space. Artists always want to pack shows with all their favorites, and it takes a strong curatorial hand to rein in that impulse. Though maybe a packed show makes sense here, if the whole point is to awe the public with a colorful barrage of famous faces—you know, give ’em the old razzle dazzle.

As a Western New Yorker with a remarkable illustration career, Burke is deserving of BPAC recognition, but filling the museum with his work for nearly half a year seems excessive. Still, it’s a fun show. Bring the young ones.

Artist, educator, and writer Bruce Adams writes regularly on visual art and other topics for Spree.