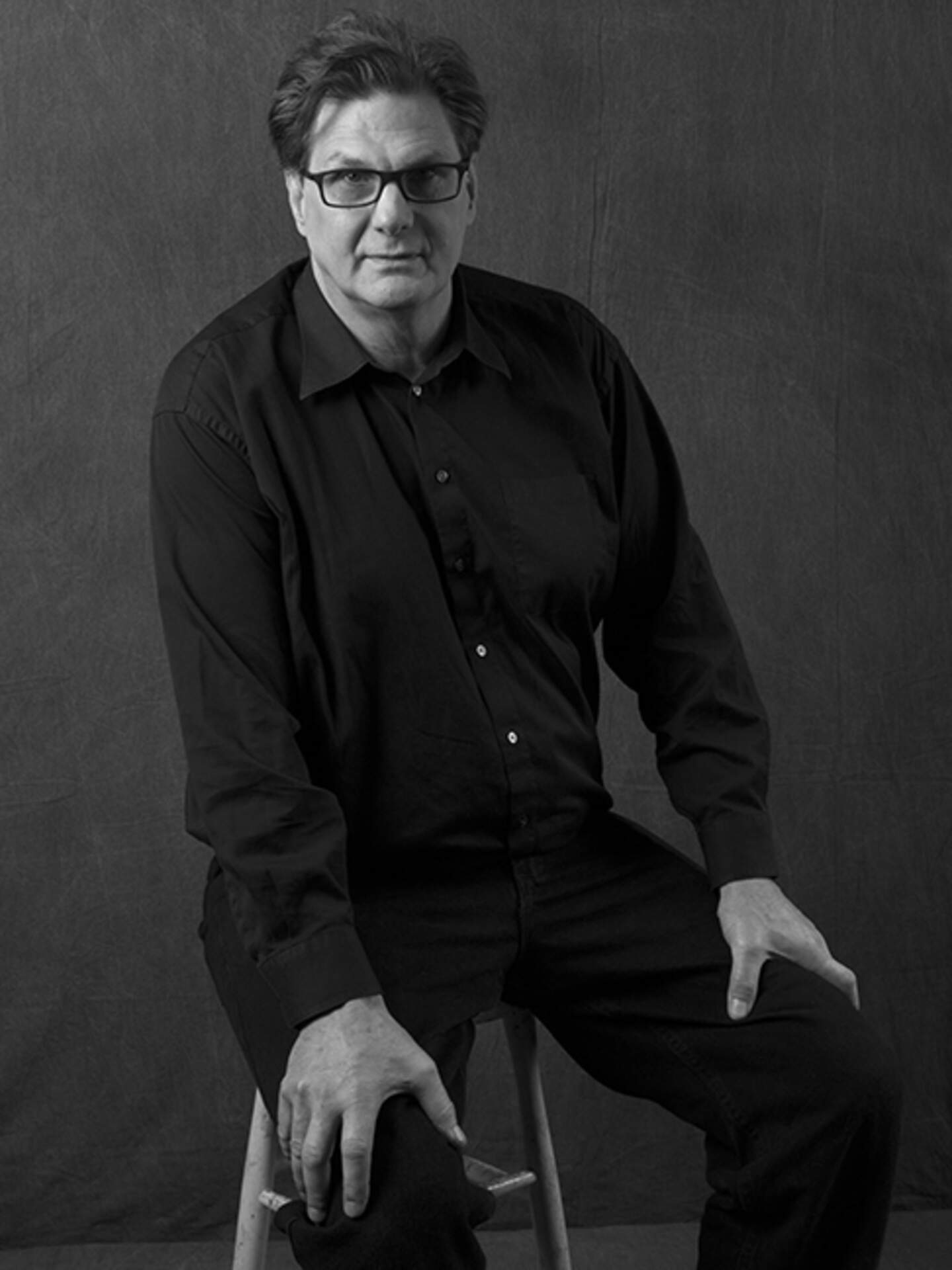

David Moog (b. 1944), Bruce Adams, 2015; Archival inkjet print, 20 x 15 inches; Gift of the artist, copyright David Moog, 2015

David Moog in Buffalo Spree

Wednesday, Jul 8, 2015

Some photographers favor arduous long-term projects. They work in thematic series, picking a subject and exhaustively documenting it. Maybe it’s the sheer challenge of thoroughly exploring a single facet of the world. Or maybe it’s that the camera is the ideal vehicle for such profound chronicling.

David Moog is not such a photographer. The seventy-year-old artist has been making pictures of one sort or another for half a century. “In all that time, I’ve been reluctant to impose any projects on myself,” he says. “Anyone with even a casual interest in photography knows that photographic projects are abundant: a series on mountains, a series on native Alaskans, a series on wild horses, and so on. Such an approach to camera work has never been appealing to me, so I’ve always avoided it.”

In the early 1970s, Moog opened a photographic illustration studio in Allentown and built a business-to-business advertising agency. Throughout his career in the ad business, he kept his personal art-making photography separate from his professional work. “From the age of twenty-five to sixty-seven, I never exhibited [my art] photographs, rarely showing them to anyone, including family members,” Moog says. But in 2011, he retired from advertising, and emerged as a visual artist, and, in February 2015, he began work on his first large-scale photographic series entitled, Artists Seen: Photographs of Artists in the 21st Century. For a guy who always avoided big projects, this one is a humdinger. “My goal is to create a portrait of every visual artist and many of the musicians who live in, work in, or are somehow connected to Western New York,” Moog states.

As anyone paying attention to the local art scene knows, there are an awful lot of artists already working in town, while area colleges continually pump out a fresh supply. The task of photographing every single one could stretch on for decades. “I’ve set an artificial deadline of three years for accomplishing the task,” says Moog, “but who knows if that’s a realistic timetable?” To further complicate things, all his potential subjects must do to qualify is declare themselves to be working artists. Other than that, the parameters are pretty broad. “I would need painters, sculptors, engravers, potters, ceramic artists, wood carvers, furniture makers, photographers, musicians, gallerists, curators, and critics. As we all know, what looks good on paper is not always doable,” Moog adds (in something of an understatement). Not surprisingly, the project has been expanding exponentially.

Moog’s ally in his quixotic quest—the Burchfield Penney Art Center (BPAC)—is a museum dedicated to artists of Western New York. Executive director Anthony Bannon and associate director Scott Propeack have greeted Moog’s proposal with enthusiastic support. “His idea perfectly intersects with what we had started with our Arts Legacy Project, an online record of the artistic heritage of Buffalo and Western New York,” says Propeack. “This was not something that we sought out, but we have such respect for David’s photographic practice and history, it’s a natural.”

Propeack notes that Moog is generously donating his service, personal equipment, and materials to the project, making it financially feasible for the museum. Moog, in turn, praises the support he is receiving from the BPAC, which has provided a generous space to set up a studio, near the museum’s entrance—within view of the public. The museum has also provided staff to assist in preparing the studio, and word-of-mouth access to artists, enhanced by its visibility and standing in the community. Perhaps more importantly, they are providing moral support. “They have encouraged, in my work, a form of photography not often given exposure in Buffalo galleries,” says Moog, “I will always be extraordinarily grateful.”

Moog’s approach to portraiture is partly inspired by his vivid memory, as a high school student, of seeing a portrait by the renowned fashion photographer, Irving Penn. He didn’t know who Penn was or who the person in the picture was, but the future photographer’s attention was riveted by the image. “Here was this old man staring at me from the black and white page as though he could see me, just as clearly as I saw him.”

Later, as a college student, Moog studied with Arnold Gassan, and the renowned photographer and philosopher Minor White, “two image makers with intensely personal, if not mysterious, objectives for making photographs.” He also studied the portrait work of such well-known practitioners Richard Avedon, Edward Weston, and Diane Arbus and came to the conclusion that “knowing the identities of the people staring into the lens isn’t at all important. The portraits are, I think, about all of us.”

In the BPAC studio, Moog uses a Japanese reflex box camera once favored by fashion photographers, which has been modified for extreme high-resolution digital capture. The images are transmitted directly to a computer, and artists are invited to watch as their images are converted to black and white and minimally adjusted. It’s a complicated technique, which, the artist explains, “has been designed to result in very uncomplicated looking photographs.

Moog unifies all the images by maintaining a consistent visual style—dramatic chiaroscuro lighting and rich velvet tones, with the artist gazing into the lens. Individual portraits range from close-up headshots to full-length portrayals, with a range of individualized gestures and expressions. “Artists frequently ask me how I determine which pictures will be close-up or full-length,” says the artist. “It’s based on some intangible, intrinsic value. I can’t explain it.” He doesn’t know most of the artists when they arrive, Moog explains, “but something transformational occurs—at least for this photographer—and the result is often a picture that neither the subject nor the photographer could have predicted.”

“He’s one of those people you feel might have been a friend for years if you hadn’t just met him,” says Candace Masters, one of seventy-five plus artists Moog photographed in the project’s pilot phase. “When I arrived, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I was a little nervous, but David has a gentle demeanor and sense of humor that quickly creates a feeling of casual familiarity. Within a few minutes, we were all laughing and sharing stories.”

The photographs are printed in fifteen-by-twenty-inch formats for archiving and future exhibits, and they will also be on continuous display on the BPAC website. “One-hundred years from now, I’d like to think gallery visitors will enjoy ‘meeting’ us,” says Moog, “the people who made art at the turn of the century.”

And how about the photographer? Who will take his picture for posterity? “Scott asked me to track myself for three years, once a week,” Moog says. “So I set lights and sit or stand in front of the camera and ask someone else to make an exposure. Just one exposure, no matter the results.”

Artist, educator, and Elmwood Village resident Bruce Adams is a longtime writer for Spree.

Read more at www.BuffaloSpree.com.