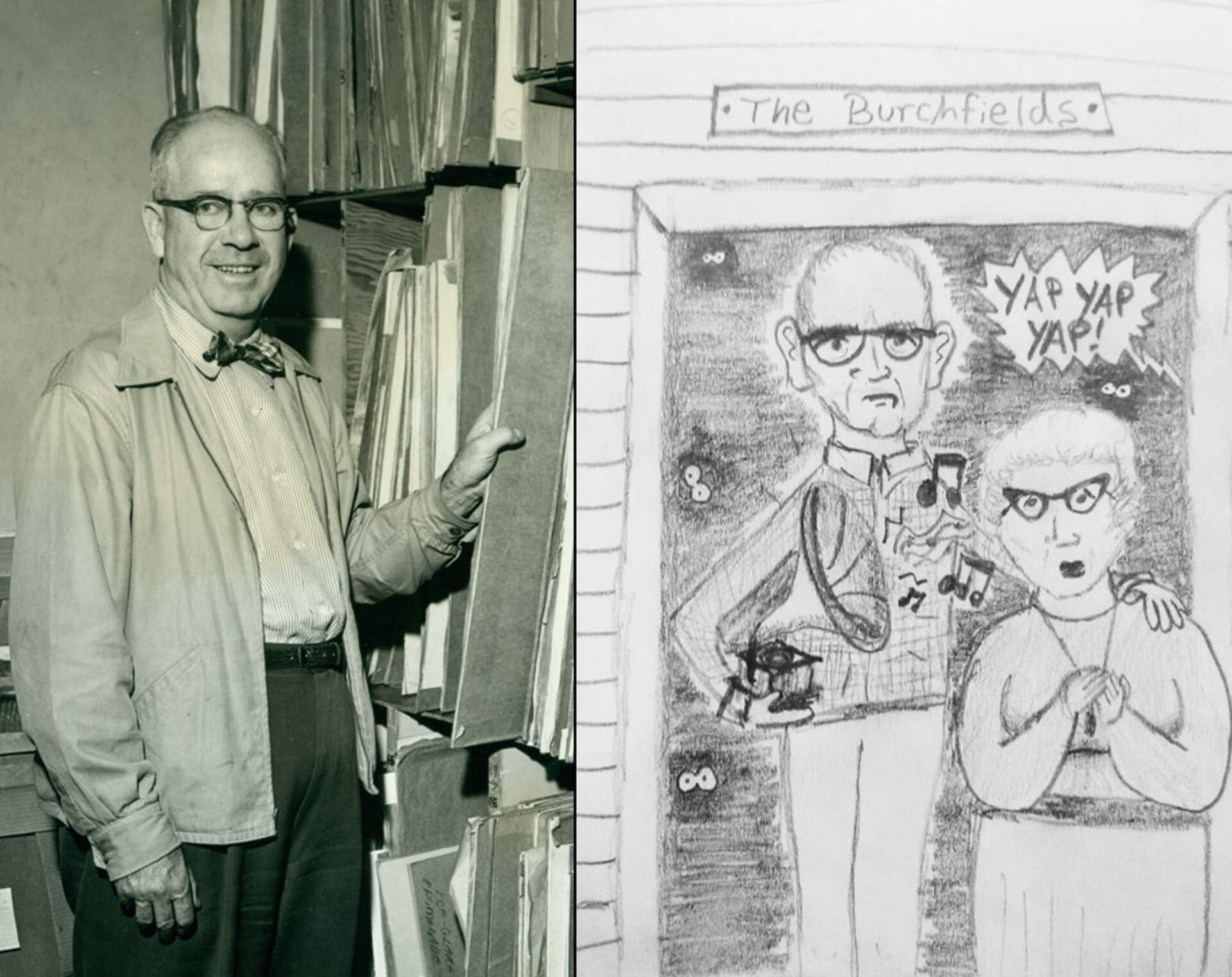

Charles Burchfield photo courtesy of Burchfield Penney Archives. Crude sketch by Kelly Donovan.

"Burchfield's Humor" by Kelly Donovan

Monday, Jul 1, 2013

If you’ve ever seen pictures of Charles Burchfield, you’ll notice that he doesn’t smile much. In fact, finding a photo of Burchfield smiling for this post took a bit of digging around in archives. Burchfield wasn’t always stoic, but rather, it seems that he maintained this nonchalance in the public eye (as well as for photographs) while allowing his family and friends to see his jovial side. This week, I’ll be sharing with you an excerpt from the 1967 Burchfield Commemorative Program. Inside, an autobiographical summary of Burchfield’s life was published (transcribed below). Burchfield’s caricature of himself teases his critics while expressing his witty humor in a way that reveals his modest view of his success.

Charles Burchfield was sensitive to the rather irrelevant inconsequentials of reporters and critics who referred to him as “tall, taciturn, and grim” and “looking more like a banker than an artist,” although he didn’t let on publicly. In the following hitherto unpublished material, he mimics the prose and predilection of the writers, and at the same time lets us in on a delightful sense of humor that was revealed only to his intimates.

THE BURCHFIELD DOMICILE

Let us pay a little visit to the Burchfield domicile. There at the door of an old mousy donnicker you will be met by Mr. Burchfield, tall, taciturn and grim; supporting on one arm his great, gray clapboarded wife, and holding on the other a Victrola which plays Sibelius incessantly. In the background may be heard the yapping of their man-eating Springer Spaniel, Pal.

Burchfield’s children (there are five of them at the last counting) are very shy like their father, and it is rarely possible to get a glimpse of them. At the first ringing of the doorbell they scramble for some convenient hiding place. Mary Alice, the oldest, who likes to play with aviator’s gloves, will scuttle back of Mrs. Burchfield’s secretary desk. Martha, paint brush dangling from a ring in her nose, flies upstairs; while Sally, her mouth full of butterflies, crawls under the living room rug. Catherine, not to be out-done, hops nimbly into her cello, which she has just suspended from a chandelier; and lastly, Arthur, the only boy, is nestling safely under a ton of coal in the basement, playing with his radio, (and toes).

Try as you will, it never seems possible to get the subject away from Burchfield or his work, and after a couple of hours of this you go away, feeling that there may after all be other things in life, but is it worth all the struggle to find out what they are?

BURCHFIELD BIOGRAPHY

On the night of April 9, 1893, Charles Burchfield was born on a pile of old clapboards in the middle of Ashtabula Harbor. Just what his mother was doing in the harbor at a time like that is not known for sure, but it was rumored that she was watching a procession (in canoes) of Bryan enthusiasts.

Even at that tender age (approximately one minute) Burchfield displayed his unusual ability by swimming unaided to the town, where he enabled his parents to set up housekeeping in William St. A few days later, as she sat looking at the tall, taciturn, and grim infant in her lap, his mother sighed and remarked: “Just to think—some day pictures by this boy of ours will be sold at the Rehn Gallery at anywhere from $500 to $3500; it just doesn’t seem possible. By the way, Pa, who is this Mr. Rehn?”

The young boy’s tailor, who was a father at the time, soon had ready a set of made-to-measure diapers, which were the envy of all his playmates. And so our budding artist waxed his hair and grew grimmer day by day. A few games of mumbly peg; a few excursions to the country for black polly-wogs; and lo, he is a young man already.

Then dressed neatly in one of his handmade diapers, and in his hand a high school diploma, he found his way to the Cleveland School of Art—where he came under the influence of a Chinese laundryman, who taught him to paint Store Fronts. It just so happened at this time that the Metropolitan Museum was looking for a good painting of a Store Front, and they eagerly purchased Mr. Burchfield’s first essay in this particular genre.

With the money he received from this sale, Burchfield bought an estate of one-third acre in the country, to which he retired, determined to devote the rest of his life to publicity for his work. (Mr. Burchfield always has insisted that he worked at the Birge wallpaper mill from 1921 to 1929, for the sheer fun of it). From this time on his fame was insured by Lloyds (who will insure anything) at a very high rate indeed.

In 1937, entering a competition sponsored by the Metropolitan Infernal Machines, Burchfield received seventh honorable mention for his painting titled “Night Thoughts of a Grasshopper.” In this he portrays the anguish of an aging Grasshopper, which, mourning for its lost childhood, sits locked in a dark closet, brooding on the enigma of the August North. This is one of the tenderest and at the same time, most brutal of Burchfield’s creations, and justly deserves the niche in the cellar of the Hall of Fame to which it has been consigned.

Recently, on the opening of the great Burchfield introspective exhibition at Albright Gallery, the artist, — tall, taciturn and grim, (looking more like a rangy supreme court Justice than the graying banker from whom he had borrowed money), was seen shaking hands with himself all evening, and lightly working up and down his right foot, which was connected with a mechanical back-slapper of his own invention.

Kelly Donovan is a student at SUNY Buffalo State, who is currently interning at the Burchfield Penney Art Center. She studies Art and is working towards a minor in Museum Studies. Kelly is from Buffalo, and lives in Amherst, New York. She participates on campus as a part of the Muriel A. Howard Honors Program, Student Ambassadors, Art and Culture Enthusiasts, and the Wilderness Adventure Club. Kelly enjoys maps, bikes, estate sales, computers, and dogs. She hopes to fly a plane someday soon and her blood type is A negative.