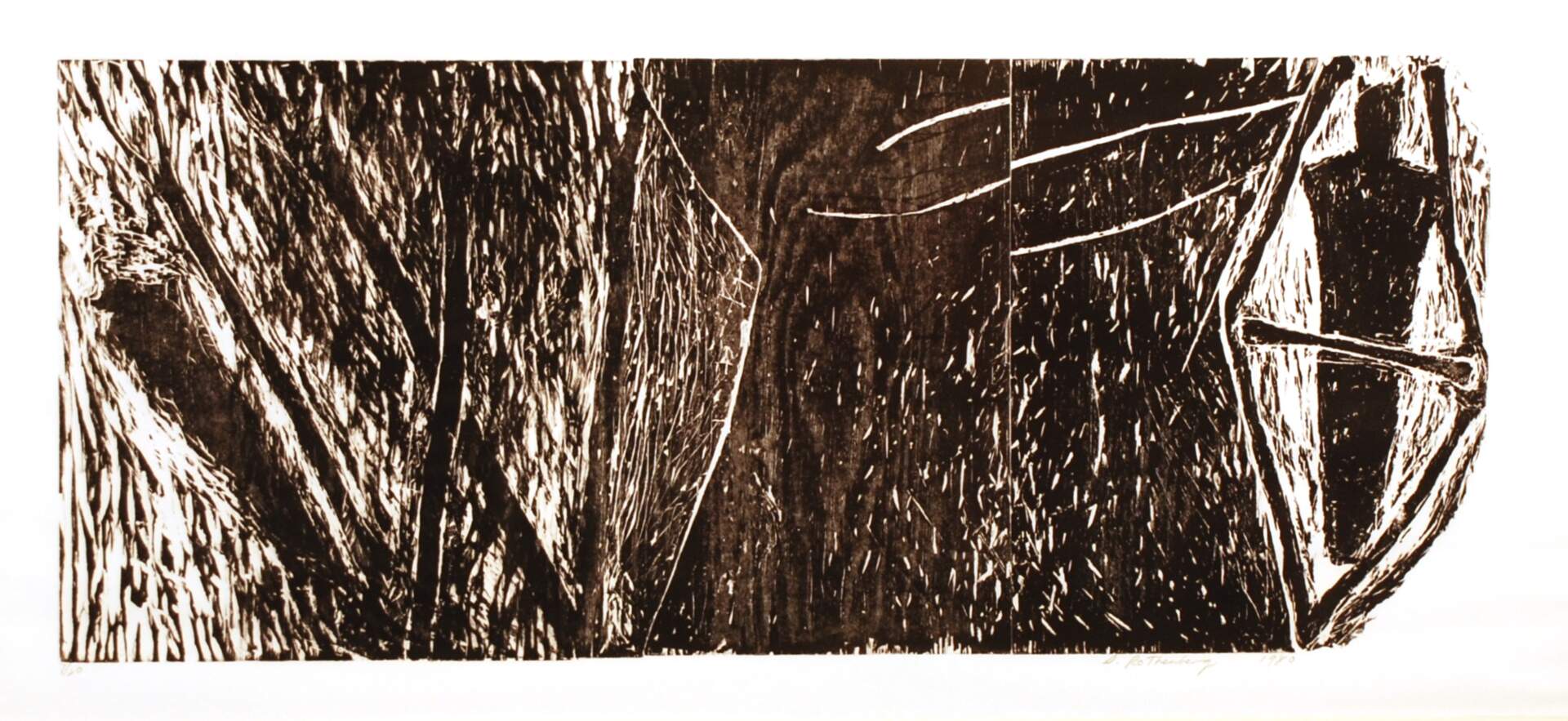

Susan Rothenberg (1945-2020), Doubles, 1980; woodcut on paper, 25 1/2 x 40 inches (frame: 28 1/4 x 40 1/4 inches); Gift of Mr. & Mrs. Armand J. Castellani in honor of Edna M. Lindemann, 1985

A Tribute to Susan Rothenberg (1945-2020)

Tuesday, Jun 16, 2020

Susan Rothenberg earned international acclaim as a courageous artist strong enough to pursue her vision when it defiantly rejected the status quo. Extensive numbers of exhibition essays, articles, and other texts explore her life and accomplishments, from her roots in Buffalo, New York to her later life in New Mexico. We have a special place in our hearts for Rothenberg because of those roots. Many of us admired the retrospective organized by Michael Auping for our sister institution, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in 1992, that traveled through 1994 to the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., The Saint Louis Art Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Seattle Art Museum, and the Dallas Museum of Art. (After leaving Buffalo, he also organized the survey, Moving in Place at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth that traveled to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico and the Miami Art Museum in 2009-2011.)

As reported by her gallery Sperone Westwater, when Peter Schjeldahl wrote a review of the Albright-Knox’s retrospective, he harkened back to her first solo exhibition held at the alternative space 112 Green Street in SoHo in 1975, that consisted of three large abstract paintings of horses. He called it “a ‘eureka’ moment because, for him and some artists, it brought painting back from the dead having ‘introduced symbolic imagery into Minimalist abstraction.’” The next big break came in 1978, when she was included in New Image Painting at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. These exhibitions catapulted Rothenberg to the forefront of the American art scene with her fresh approach to painting that advanced beyond both non-objective Minimalism and cerebral Conceptualism.

In a special issue on Expressionism in Art in America, published in December 1982, Rothenberg discussed the evolution of her imagery:

The way the horse image appeared in my paintings was not an intellectual procedure. Most of my work is not run through a rational part of my brain. It comes from a place in me that I don’t choose to examine. I just let it come. I don’t have any special affection for horses. A terrific cypress will do it for me too. But I knew that the horse is a powerful, recognizable thing, and that it would take care of my need for an image. For years I didn’t give much thought to why I was using a horse. I just thought about wholes and parts, figures and space.

Then I did the human heads and hands. I started with 9-inch studies—mesmerizing at that size, and I suppose I connected to it because that’s what I work with, a head and a hand, and I thought, why not paint it. Then I blew them up to 10 x 10 feet and they became very confrontational.

Not unlike the Abstract Expressionists, she relied on intuition and confidence to direct her creative output, both in terms of subjects and mark-making. Lisbet Nilson reported the artist musing on this aspect of her work in “Susan Rothenberg, ‘Every Brushstroke Is a Surprise’,” for ARTnews in 1984:

“Right now, I am feeling very much the way the wind blows me—in fact, in two of these paintings there is actual painted wind, which is how literal I can get sometimes,” Rothenberg is saying. “I just don’t feel locked into any system of painting anymore. Whatever a painting seems to want I try to provide. I guess I got confident. I know I have a couple of kinds of energy that will make a surface that feels like me, feels comfortable to my brain, my eye, my art. I like to play with that.”

Fast forward to the next decade, when Cheryl Brutvan, a former Albright-Knox Art Gallery curator, organized Susan Rothenberg: Paintings from the Nineties for The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1999. The introductory paragraph of her intriguing catalog essay begins:

Susan Rothenberg’s canvases from the last ten years form a powerful body of work from a period of time defined by significant changes in the artist’s life. While the paintings since 1990 reveal evidence of the knowledge the artist has gained from every previous painting, drawing, and print, there are also notable differences between these paintings and her earlier work. Consistent is Rothenberg’s abiding interest in imagery and her need to continually seek out something that elicits an emotional response before putting brush to canvas. Yet, these paintings are, above all else, evidence of the artist’s increasingly complex relationship with her medium.

Susan Rothenberg had numerous solo exhibitions in the United States and abroad, including early presentations at Kuntshalle, Basel (1981-82), the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1982), and an exhibition organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art that traveled to seven institutions in the United States and abroad (1983-85). Others include a survey in El Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Monterrey, Mexico (1996-97) and an exhibition of drawings and prints at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University which traveled to the Contemporary Museum, Honolulu and the Museum of Fine Arts, Santa Fe (1998-99). As reported by Sperone Westwater, which has represented her work for the past thirty-three years, Rothenberg’s work is in important public and private collections, including the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo; Hall Art Foundation Collection (situated in Derneburg, Germany and the U.S.); Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Tate, London; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Robert Storr is one of the best writers who has expounded on Rothenberg’s work. In “Susan Rothenberg, Disparities & Deformations: Our Grotesque,” for SITE Santa Fe in June 2004, he articulated her process so precisely:

The images in a painting by Susan Rothenberg is the last stage of an incremental process of statement, revision, cancellation, and restatement. In this cycle the subject may be well defined at the start or vague, something that accumulates around a firmly delineated form, or the gradual coming into focus of what tat the outset was only dimly perceived. Attrition or erosion may also be factors. Some pictures constitute the residue of many decisions in the course of which the original premise has been lost or has morphed into something initially unforeseen. All of which is to say that Rothenberg’s style is the organic product of her method. In her work the imagination comes alive on the material surface of a pigment-loaded canvas; premeditation just gets things rolling. Once that starts, the only check on where they go is the authenticity of the marks required to bring the image into being and the critical intelligence that ponders the result, is convinced by it, or compelled to transform it yet again.

Rothenberg’s paintings exhilarate the senses. Personally, one of my fondest memories is visiting Sperone Westwater when the gallery was in the Meatpacking District at 415 West 13th Street to see her solo exhibition and to identify available work that might interest a potential patron to purchase. What a remarkable experience, standing in front of her mammoth canvases in the gallery all by myself. As we know, illustrations cannot do justice to seeing artwork in person. The scale, the textures, the nuances of colors, all immerse you in a highly meaningful, subjective space that is both physical and intellectual. Regrettably, we were not able to purchase any of my favorite paintings; but the Burchfield Penney Art Center does own five prints and a drawing that I present below.

In 1980, two years after the Whitney Museum of American Art included Susan Rothenberg in New Image Painting, artist Diane Bertolo (a Hallwalls co-founder and part of the Buffalo avant-garde now living in Brooklyn), wrote about the relationship between her recent woodcuts to her paintings. Rothenberg had pioneered a return to recognizable imagery, following the reign of Minimalism and Conceptualism in the artworld. In her review of the prints shown at Brian Art Galleries in Buffalo, Bertolo described the “images of bones and vaguely human form [that] figure into more complex compositions,” noting that they “are a striking contrast to the earlier works of the sensuously brushed, pink-colored horses.” In my opinion, the rough texture of woodcuts closely mimics the painterly surfaces of Rothenberg’s canvases, although achieved by entirely different techniques. Imagery emerges suggestively from shadowy, ambiguous spaces. Bertolo continued with a reading of the print, Doubles:

In “Doubles,” lines divide the picture plane but in a more aggressive manner as if they were X’s crossing out the image rather than defining form. Bones are aligned to frame an armless figure. It is a puzzling and darkly psychological work somewhat reminiscent of woodcuts done by the German Expressionists in the early part of this century.

This affinity with early 20th-century German Expressionist woodcuts, as well as prints by Norwegian Edvard Munch (1863-1944), is further demonstrated when Doubles is compared with the other two 1980 woodcuts that were donated by Mr. & Mrs. Armand J. Castellani in honor of Director Edna M. Lindemann’s retirement in 1985. Head and Bones contains the skeletal horse imagery among crossing lines and bones that resonate with Rothenberg’s ground-breaking paintings of the 1970s. Head and Hand echoes the human figurative elements in the work that followed. By keeping the palette restricted to black and white, she elevates the intensity of angst despite the smaller scale of the prints in relation to her huge canvases. Little Heads (1980), a 3-color woodcut on paper of diminutive size, is even more terrifying than Munch’s infamous The Scream (1893) because the elements have been reduced to essential glyphs—a black head in profile outlined with agitated white lines seeming to call or yell or scream, thus projecting this voice by holding up a mustard-colored hand to direct the message further. Pale vertical lines above an ochre background suggest a fence or even prison bars. How powerful a message of anguish!

The American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters in New York City awarded the (then-named) Burchfield Center the Hassam and Speicher Purchase Fund, enabling the museum to purchase an original drawing by Susan Rothenberg in 1984. By this time, she was so famous that the prices on her paintings placed them beyond our reach, and she was only represented in the collection by one small print—albeit a rare trial proof from a small edition of 15. Two slender figures emerge from a whirlwind of marks suggesting an ambiguous space in the untitled oil and charcoal on paper drawing. Their heads touch in a gravity-defying, right angle connection. The horizontal figure appears to be anchored to the right edge of the drawing, its feet providing a point of contact. The vertical figure lacks feet, so it hovers in limbo. Is this a dream? Could this be a view from above reclining figures? Does it convey sexual longing? Is it a “meeting of the minds”—a symbolic gesture of metaphysical union? There is no distinct, intended interpretation. Instead, Rothenberg always wanted her work to elicit emotion. Contemporary art allows the viewer to bring individual, meaningful interpretations, which can be multiple, as we explore the unconscious realm in which these ideas and emotions reside.

In music, the term “mezzo forte” means “moderately loudly.” Applied to the title, Mezzo-Fist # 1, Susan Rothenberg may be implying a moderately forceful threat; however, considering the print’s very dark palette and the clenched, pumping fist that appears almost the same size of the man’s head, one might feel intimidated by the looming menace. Rothenberg also appears to be punning on the primary method of producing this mezzotint print that produces modulated tones that mimic her painting style, allowing subject matter to emerge with a flurry of white lines out of an undefined, mysterious background space, which in this case is nightmarish. Mezzo-Fist # 1 may have been created in 1990, but it conveys the current socio-political climate of our nation as we confront racist brutality in the centuries-old struggle for equity and equality for all people.

Susan Rothenberg’s work was ever evolving, always intense. In 2020, we look back with pride on her being from our region and we pay tribute to the incredible body of artwork she produced.

— Nancy Weekly

Burchfield Scholar, Head of Collections, Charles Cary Rumsey Curator, Burchfield Penney Art Center & Burchfield Penney Instructor of Museum Studies, SUNY Buffalo State