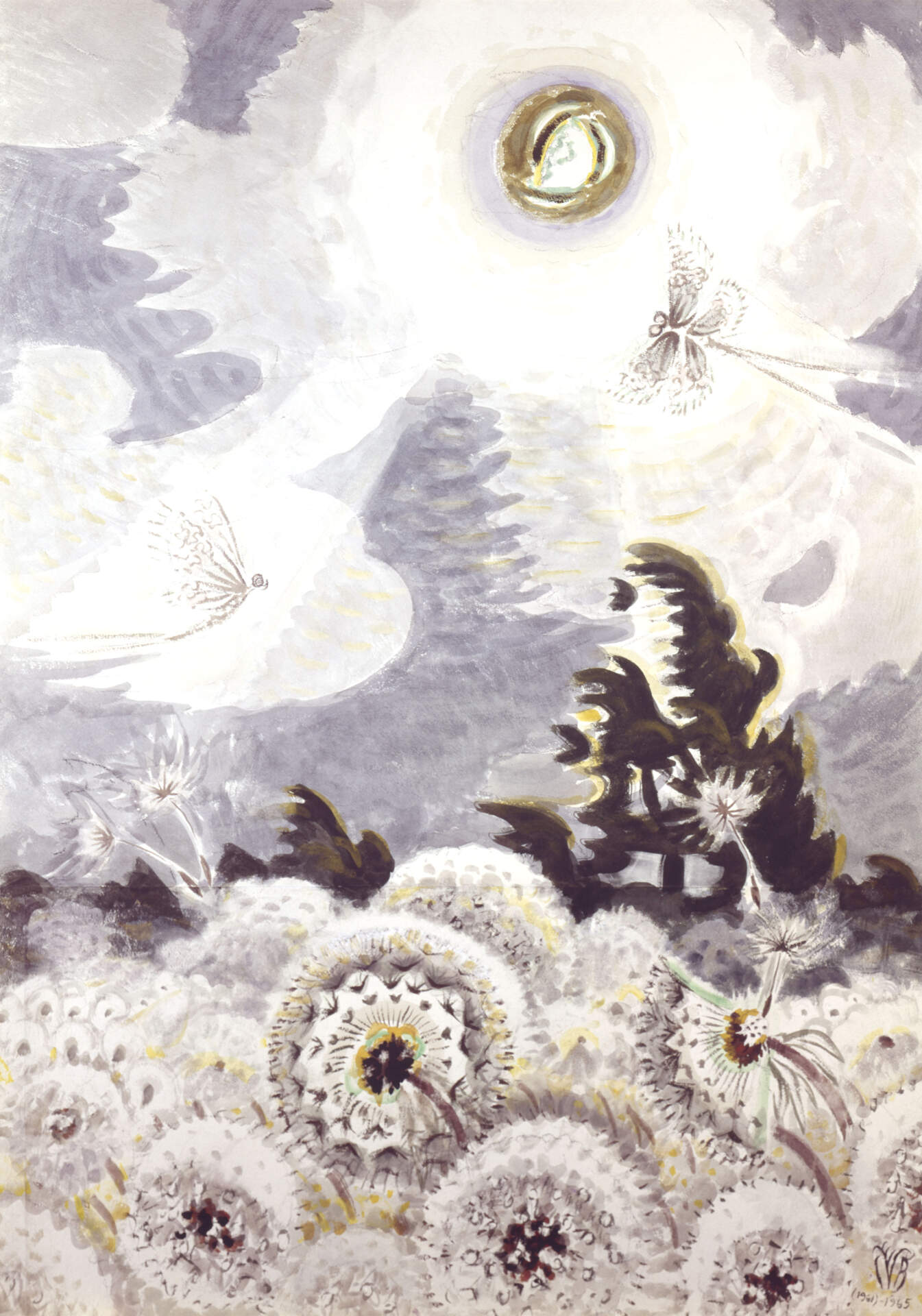

Charles E. Burchfield (1893-1967), Dandelion Seed Heads and the Moon, 1961-1965; watercolor, gouache, charcoal, and sgraffito on lightly textured white wove paper faced on 1/4-inch-thick laminated gray chalkboard, 56 x 40 inches; Karen and Kevin Kennedy Collection

"Art from a Mathematical Perspective" by Kelly Donovan

Thursday, Jun 6, 2013

Last Tuesday, May 28th, seven students from the Park School of Buffalo came to the Burchfield Penney to present their class project on the exciting connections between Burchfield and Vector Calculus. Titled The Calculus of Burchfield, the students graphed the vectors present in the backgrounds of Burchfield’s paintings under the direction of their teacher Bill Fedirko.

Before going further, it is important to know about vectors and scalars. Scalars are anything that has a magnitude, for example, 5 meters, 20 degrees Celsius, or 300 calories. Vectors are scalars that also have motion applied to them, meaning they have both magnitude and motion—like 5 knots north, or 60 mph west. Things that are measured in Vectors include wind speed and weather patterns. These movements are visible in Burchfield’s stylized works, such as Dandelion Seed Heads and the Moon where the dandelions are swept up in a windy day. Other works show vectors in the heat waves and radiating qualities of trees, houses, or telephone wires, such as in Song of the Telegraph.

Mr. Fedirko encouraged the students to find out the equation for the vectors present in these paintings. These vectors are visible in the red arrows overlaying the paintings. It wasn’t all easy to do, however. The students had to test many different vector equations to find a good match, and then shift the graph around to find the best fit. Sine and Cosine equations make up the swirling brushwork around the moon, for example. Even through this meticulous process, the results aren’t perfect. Burchfield’s creative license produces a few kinks, such as the dandelions that curve opposite the rest. Even so, the motion present in the work is undeniable.

To help envision this motion, the students wanted to make different graphs instead of the red arrows. What they produced, using Maple algebra software, is an art in and of itself. Using the vectors as a base, students applied a gradient overlay. The colorful graphs that resulted resemble op art of the 1960’s.

What does this mean for Burchfield? Was he a vector genius? While that’s hard to say, Mr. Fedirko suggests that it may have been part of Burchfield’s intuition. Burchfield painted around the time when the theory of the atom and particular motion was adapting to new ideas of radiation and wavelengths, which may have also served as inspiration. Even with these scientific discoveries, Burchfield painted directly from nature, recording the dynamism that is omnipresent. But to graph all of these motions and movements would take an infinite amount of time. “Some things are so awesome, it’s hard to imagine they were created without a God,” Fedirko remarked. This transcendental idealism has long been present in art, but not so much in mathematics. It’s hard to introduce something so vast and unknown into a field that is laden with answers to nearly everything. The motion present in nature is like the motion present in a vector, but whereas vectors require a constant—“What is the source of these pure [natural] constants?” Fedirko asks.

This profound question left the audience awestruck. Burchfield may have been onto the answer by recording the vectors, or changes, that happened during his lifetime—the changing winds, the stormy clouds and heat energy that hums in the natural world.

Kelly Donovan

Kelly Donovan is a student at SUNY Buffalo State, who is currently interning at the Burchfield Penney Art Center. She studies Art and is working towards a minor in Museum Studies. Kelly is from Buffalo, and lives in Amherst, New York. She participates on campus as a part of the Muriel A. Howard Honors Program, Student Ambassadors, Art and Culture Enthusiasts, and the Wilderness Adventure Club. Kelly enjoys maps, bikes, estate sales, computers, and dogs. She hopes to fly a plane someday soon and her blood type is A negative.