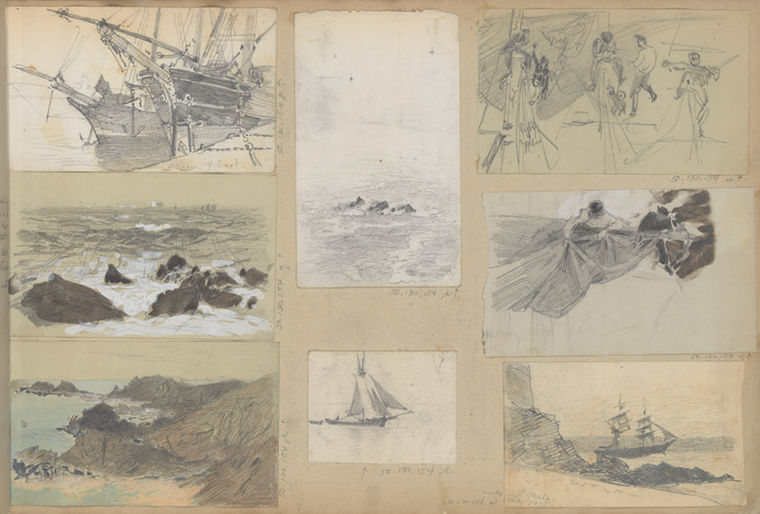

A page from John Singer Sargent's scrapbook, including sketches made by the artist during the summer 1875 when he was visiting Brittany, France.

John Singer Sargent had a lifelong love affair with Italy. Born in Florence in 1856 to American parents, he spent many of his formative years in Italy immersed in the country's history, culture, and art. Later in his life, he would return frequently to the Italian locales of his childhood with his relatives and close friends for extended painting holidays. In the exhibition American Painters in Italy: From Copley to Sargent, on view in gallery 773 through June 17, 2018, Sargent is represented by twelve watercolors and drawings that span his career, including copies after Italian art and architecture, images of idyllic gardens, and Venetian views. The preponderance of works reflects the depth of The Met collection—one of the largest and most comprehensive gatherings of Sargent's works in the world—and the artist's lasting affinity for Italy.

One of the themes explored in the exhibition is American painters' enduring interest in Italian art. From the late eighteenth century, many American artists felt compelled to experience firsthand the esteemed art of Italy—from its classical past, through the Renaissance and beyond—in order to improve their own art. Unlike the other artists in the exhibition, Sargent grew up surrounded by Italian art and internalized its messages from an early age.

Left: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Garden near Lucca, ca. 1910. Watercolor and graphite on white wove paper, 13 7/8 x 9 15/16 in. (35.2 x 25.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.81i)

Sargent's parents arrived in Europe in 1854 for a restorative holiday, which was meant to be temporary, but they never returned to live in the United States. They established a pattern of traveling seasonally in Europe, constantly in search of a temperate climate to suit their health. They tended to spend their winters in Mediterranean cities such as Nice, Florence, and Rome, and their summers in more northern regions such as the Alps.

Sargent's father, Fitzwilliam, was a surgeon from Philadelphia who gave up his position to stay in Europe. The family lived modestly on income from an annuity. Sargent's mother, Mary, was an indefatigable traveler who enjoyed exploring. She made sure that her children saw all of the important sights and monuments of every place they visited. An amateur artist herself, Mary encouraged her children to draw and paint. According to family folklore, she required that John and his two sisters finish at least one drawing each day. The precocious Sargent seems to have sketched constantly as he traveled across the continent, recording the people, places, and art that captured his attention.

Sargent became an artist in Italy. Living in Rome and Florence in the late 1860s and early 1870s, he was fascinated by the art of the classical past and of the Italian Renaissance, and he began making copies after works of art at a very young age. His friend the writer Vernon Lee later described their childhood visits to the Vatican's famed sculpture collection: "There were scamperings, barely restrained by responsible elders, through icy miles of Vatican galleries, to make hurried forbidden sketches of statues selected for easy portrayal."[1] A year later, in autumn 1870, when Sargent was just fourteen years old and living in Florence, his father acknowledged his son's career goals in a letter to his own mother: "John seems to have a strong desire to be an Artist by profession, a painter."[2]

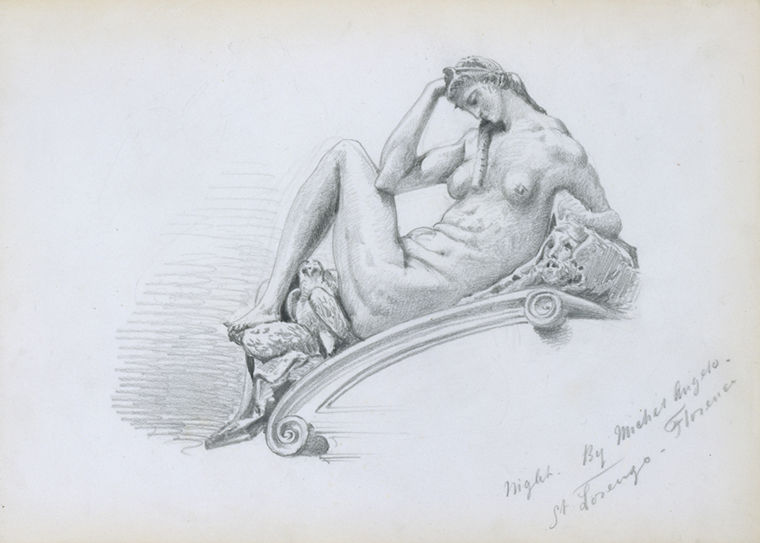

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Night, 1870. Graphite on off-white wove paper, 10 3/4 x 15 1/4 in. (27.3 x 38.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.143z)

Around this time, Sargent made his first copies after works by the great Renaissance master Michelangelo (1475–1564). While living in Florence, he was surrounded by the influence of Il Divino, whose reputation as a master of anatomy made him an artistic role model. Sargent's careful drawing after the allegorical sculpture of Night in the Medici Chapel in the Church of San Lorenzo is on view in the exhibition. The fourteen-year-old artist was challenged by the difficult reclining and twisted pose of the renowned figure. He paid close attention to Night's elongated torso, focusing on the rolls of flesh and musculature of her abdomen. Yet he seems to have struggled with the foreshortening of the left foot, and the dynamic angle of the bent right arm in relation to the bent left leg.

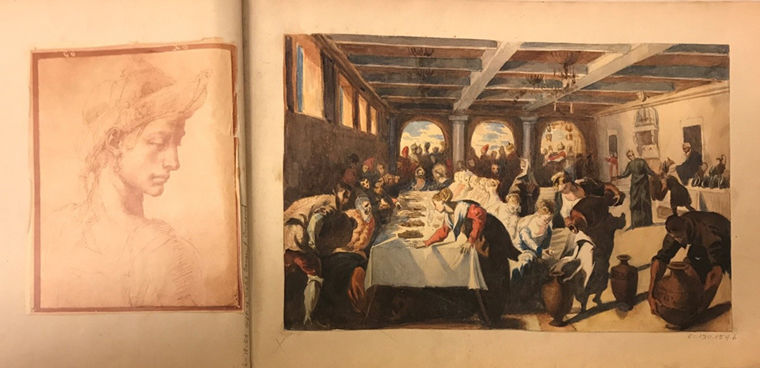

A remarkable scrapbook assembled by Sargent when he was a student in Paris between 1874 and the early 1880s bears witness to his enduring interest in Italian art. In its debut at The Met, the book displays Sargent's continued interest in Michelangelo and his esteem for the great Venetian painter Tintoretto (ca. 1518–1594). Sargent inserted a commercial photograph after a drawing by Michelangelo, Ideal Head(Ashmolean Museum), next to his watercolor copy of Tintoretto's much-lauded masterpiece The Marriage at Cana (1561). After a visit to Venice in spring 1873, he wrote to his friend Violet Paget (later Vernon Lee) about his "intense admiration for that great master."[3] In The Marriage at Cana, Sargent seems to have been attracted to the poses and gestures of the figures in the foreground that gracefully reach, twist, and bend to serve food and pour wine.

Sargent's scrapbook, as displayed in the exhibition American Painters in Italy. Left: Sargent has pasted in a commercial photograph of a drawing by Michelangelo. Right: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). The Marriage of Cana (from scrapbook), ca. 1872–74. Graphite and watercolor on off-white wove paper, 9 1/2 x 14 7/8 in. (24.1 x 37.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.154b)

Sargent's disciplined copying of works by the Old Masters prepared him well for the next phase of his artistic education in Paris, where he enrolled at a French government school, the École des Beaux-Arts, and entered the teaching studio of a rising French portraitist known as Carolus-Duran (1837–1917).

The varied material he gathered in the album provides a rare glimpse into the mind and method of the young artist at this important moment in his career. The scrapbook contains a total of fifty-three of his drawings and watercolors of diverse subjects, including works of art and landscapes made during his summer holidays. Sargent inserted more than one hundred and fifty prints and commercial photographs of works of art, architecture, and travel destinations; and cartoons and illustrations from contemporary periodicals. The scrapbook is not a chronological or comprehensive anthology of Sargent's work in this period but rather a more personal portrait of his taste and priorities.

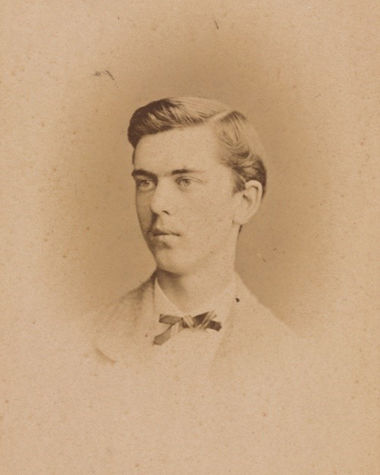

Right: Giuseppe and Luigi Vianelli. Sargent, Venice (detail), ca. 1874.Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The John Singer Sargent Archive—Gift of Richard and Leonée Ormond. Image courtesy Richard Ormond

In addition to photographs after works by Michelangelo, Raphael, Tintoretto, and other Italian artists, Sargent also copied painting, sculpture, and architecture from ancient Greece and Rome and contemporary France. He searched broadly through the art of the past for inspiration, looking at the rustic peasants of Millet, and the formal compositions of Poussin. On several sheets, he traced Egyptian motifs directly from a book. While Italy and Italian art have a privileged position in the album, the book also records his increasing infatuation with Spanish art and culture, especially the works of the seventeenth-century master Diego Velázquez (1599–1660). During a trip to Spain in 1879–80, he collected images of Velázquez's paintings in the Prado and historical sites throughout the country. The diverse material in the book reflects Sargent's curious mind and developing taste.

The creation of a scrapbook implies that the material gathered will not only be preserved but will also be referred to again. In 1879, a writer for Harper's Bazaar, reflecting on the then-trendy phenomenon of scrapbooking, likened the viewing of an album with a journey:

Ten minutes with one's scrapbook are like a voyage, a scientific convocation, an evening with the poets—any form of recreation that the tired mind desires—and the shabby home-made cyclopedia becomes the freshest book in the library.[4]

As Sargent's habit of collecting images overlapped with his compulsive tendency to sketch and record the world around him, a scrapbook must have seemed like an ideal way to preserve choice material. While we don't know how often Sargent referred back to the scrapbook, he and his descendants realized its significance, preserved it, and presented it to The Met in 1950.

Notes

[1] Vernon Lee, "J. S. S. In Memoriam," in Evan Charteris, John Sargent (New York: Charles Scribner's and Sons, 1927), 242–43.

[2] Fitzwilliam Sargent to Emily Haskell Sargent, October 10, 1870, Florence; quoted in Stephen D. Rubin, John Singer Sargent's Alpine Sketchbooks: A Young Artist's Perspective (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991), 9.

[3] Sargent to Vernon Lee, August 12, 1873, Pontresina; Millar Library, Colby College, Waterville, Maine.

[4] "Of Scrapbooks," Harper's Bazaar 12 (July 12, 1879): 438.

This text has been adapted from Stephanie L. Herdrich, "Sargent's Scrapbook of the 1870s," in Sargent and the Sea, edited by Sarah Cash (Washington, D.C.: Yale University Press in association with Corcoran Gallery of Art, 2009), 58–87.

Related Content

American Painters in Italy: From Copley to Sargent is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through June 17, 2018.

Read an interview with exhibition curator Stephanie Herdrich on Now at The Met and follow her on Instagram.

Stephanie L. Herdrich and H. Barbara Weinberg, with Marjorie Shelley, American Drawings and Watercolors in The Metropolitan Museum of Art: John Singer Sargent (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000).

Stephanie L. Herdrich and H. Barbara Weinberg, "John Singer Sargent in The Metropolitan Museum of Art," The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 57, no. 4 (Spring, 2000).

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "Sixteenth-Century Painting in Venice and the Veneto" and "Renaissance Drawings: Material and Function"