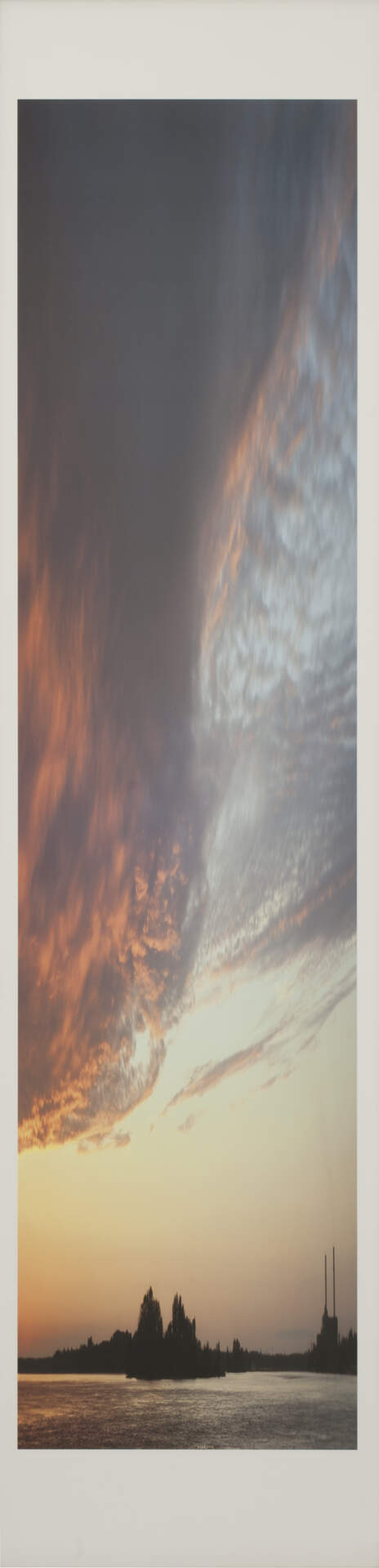

John Pfahl (1939-2020), Dark Cathedral, 2006; digital print mounted on Plexiglas with polycarbonate laminate, 83 5/8 x 20 3/4 inches; frame: 85 x 22 1/8 x 1 1/4 inches; Gift of the artist and the Nina Freudenheim Gallery, 2017

Memories of Nina Freudenheim and John Pfahl

Wednesday, Apr 22, 2020

Remembering Nina Freudenheim & John Pfahl

Expressing grief in words is a difficult task. On the one hand you want to find a way to honor the person by conveying the individual’s unique personality and finest accomplishments, as well as offer meaningful personal memories. But the pain of loss increases the fear of inadequacy to find language that is powerful or poetic enough to articulate the fullness of the lost one’s life. You procrastinate in a fog of disbelief that you will no longer be able to converse, or share experiences, or hug or kiss them. In the midst of a global pandemic, these feelings are magnified as we cannot gather to mourn together. These gatherings will be postponed until a time when our voices can be joined in reflection of the various facets of the lives led by our friends and family.

When news came that Nina Freudenheim (October 2, 1936-April 10, 2020) had passed, my immediate reaction was extreme sadness, followed quickly by a knowingly false sense of denial and disbelief because I didn’t want it to be true. My friends and colleagues commiserated. We all shared the knowledge that Buffalo lost an extraordinary woman who was instrumental in championing contemporary art and artists. She had a discerning eye that facilitated her ability to find and promote brilliant artists whose works now fill our museums, homes, hospitals, and business spaces. She was strong, intelligent, beautiful, and spoke with a beguiling, mellifluous voice. Admired as a woman gallerist, she was a role model for women in many aspects of the arts. To be honest, I applied for her assistant’s job in the early 1980s, but she didn’t want to be perceived as “stealing” me from my position at the time. We had first met around 1977, when I was the gallery director of the Michael C. Rockefeller Arts Center Gallery at SUNY Fredonia State College. Over lunch in Lord Chumley’s in Buffalo, we discussed my borrowing a traveling exhibition: Altered Landscapes, John Pfahl’s first solo exhibition. Instead of paying a loan fee, we purchased one of his photographs: Great Salt Lake Angles, Salt Lake City, Utah (October 1977). It was with great excitement that in 1978 at the Nina Freudenheim Gallery on Franklin Street, that I met John Pfahl for the first time. Nina and John will always be inextricably linked in my memory. That he would die within days of Nina has been an unbearable heartbreak.

Nina’s voice resonates in my memory and will be one of her characteristics I will miss the most. While the buzz of crowded gallery openings has its appeal, I treasure the times I viewed Nina’s exhibitions solo—when I could spend as much time as I’d like to study the work uninterrupted, followed by a one-on-one conversation with Nina about the art, life, what’s new. Sometimes these meetings resulted in the Burchfield Penney Art Center’s acquisition of art, frequently made possible through the generosity of the artist in concert with the Nina Freudenheim Gallery. Notably, we have signature works by Ellen Carey, John Pfahl, Rina Peleg, and Michael Stefura through this generous partnership. The earliest gift came from Nina and her husband, Bob: Peter Stephens’ Dove and Faun (1986), from the solo exhibition that our museum presented. On Nina’s recommendation, museum patrons also sponsored many purchases and made direct donations. Thanks to her encouragement the Center benefitted from the acquisition of works by Brendan Bannon, Kyle Butler, Virginia Cuthbert, Mark DiVincenzo, Joan Linder, John McQueen, Alice O’Malley, Christy Rupp, and Katherine Sehr, to name just a few. They are among the great number of artists whose works were featured in her gallery in cutting edge, intellectually stimulating, and aesthetically breathtaking solo and group exhibitions.

Creating art galleries in Buffalo where none had existed before, Nina mastered the art of architectural reuse. Her first gallery opened in 1975 at 560 Franklin Street, which was built in 1867 as an addition to a private residence. Consecutively, it was taken over by St. Margaret’s Episcopal School, St. Mary’s Seminary, and the New School of the Performing Arts. Around the perimeter of one of Nina’s gallery spaces with a skylight, you could see the second floor running track when it was used as a girls’ gym. This was the space where she featured sculpture by then-emerging ceramic artists Bill Stewart and David Gilhooly, among so many others. Her second gallery on Delaware Avenue reflected the glamour of the most fashionable business neighborhood in the city. Here exhibitions ranged from a significant retrospective with a catalog celebrating Virginia Cuthbert to an almost secret exhibition tucked away upstairs of small, moving photographs of John Pfahl’s views from his hospital room window as he recovered from life-threatening illness. Brilliantly, she opened her Niagara Street gallery with Fred Sandback: Sculpture and Drawings in October 1989. His minimalist string sculptures were a clever way to highlight the raw space, converted from an agriculture supply storage facility, into a dramatically lit, sophisticated play between art and architecture. Her final home at 140 North Street in the Lenox Hotel was a warm, welcoming suite of three connected galleries, one containing a fireplace, all with windows allowing natural light to filter in. You took a quick turn into a library and guest book nook, and opposite that found the entrance to her office which also served as the reception space, where more information about the exhibited artists and checklists could be found, as well as fresh flowers. Here at a little table/desk and two chairs, you could have a comfortable, lengthy conversation during weekday visits, followed by a meander through the galleries discussing favorite works.

Nina Freudenheim was also an advisor and consultant for other museums like the Albright-Knox Art Gallery and businesses such as Rich Products. Notably, public sculpture projects served a wider audience. She conceived a novel project for SUNY Buffalo many years ago in which several sculptures were located around the North campus for a year’s loan, after which UB decided which one piece was the best for acquisition. They had the benefit of enjoying the art while having the time to reflect on each work’s merits. Even grander was her consultancy for the Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority. Through a competition, more than 500 artists submitted proposals for the interior and exterior of the newly built Light Rail Rapid Transit System stations. The NFTA commissioned 22 artists in 1983, their work was completed 1984-85, and we still enjoy it today. Buoyed by her national and international travels, Nina developed a perfect understanding of contemporary art right for this time and place. We will miss her tremendously as both a friend and colleague.

Among Nina Freudenheim’s superstars was John Pfahl (February 17, 1939-April 15, 2020). I burst into tears when word of his passing came just days after hers. I had just sent a sympathy card to John and his wife, the equally talented artist, Bonnie Gordon, because they were so close to Nina; how could it be possible for them both to be gone? I turn to his art to speak for who he was.

John Pfahl became a world-renowned artist who addressed critical subjects in series of photographs that reflected his intellectual mind with sophisticated aesthetics, photographic historicity, wry humor, and utter seriousness. By examining some of his life’s work, we can gain insight into his multi-dimensional persona. Take for example his earliest series, Altered Landscapes (1974-1978) created in playful response to the growing practice of darkroom manipulation of images. With tongue in cheek, John physically altered the landscape he viewed through the lens, not the prints or negatives. What a difficult challenge it must have been to align small strips of blue tape on three rugged wooden doors to simulate a level dotted line in perfect perspective for Shed with Blue Dotted Lines, Penland, North Carolina, June 1975. Mischievous in both title and image, Wave, Lave, Lace, Pescadero Beach, California, March 1978 conjures a game in which you change one letter of a word, each time creating a new word with a different meaning. John constructed a physical illusion mimicking the words’ transition in a photograph to be read from top to bottom. Frothy ocean foam washes over the sandy shore resembling an old-fashioned lace petticoat as seen from an upper promontory where he set two strands of lace over shrubs. Doesn’t it make you laugh out loud?

More of the time John was serious in his creation of landscapes meant to stimulate a commitment to seeing both the exquisite beauty of the land and its desecration so we would be motivated to save it. Demonstrating a mastery of language as well, his series statements reveal the extensive art historical and literary research he conducted in deep contemplation of his objectives. Describing the background for Power Places (1981-1984), he wrote: “For me, power plants in the natural landscape represent only the most extreme example of man’s willful domination over the wilderness. It is the arena where the needs and ambitions of an ever-expanding population collide most forcefully with the finite resources of nature.” He continues with what would become a recurring theme for his work:

It is not without trepidation that I have appropriated the codes of "the Sublime" and "the Picturesque" in my work. After all, serious photographers have spent most of this century trying to expunge such extravagances from their art. The tradition lives on, mostly in calendars and picture postcards. I was challenged to rework and revitalize that which had been so roundly denigrated.

Similarly, in Smoke (1988-1989), the “prodigious display of smoke bursting forth from stacks of the Bethlehem Steel coke operation in Lackawanna, New York,” when seen from certain perspectives, might be perceived as “a phantasmagoria of light and color” that both “simultaneously attracted and repelled” him in the 19th-century sense of the sublime, displaying beauty and provoking fear at the same time.

Missile/Glyphs (1984-1985) is a series of diptychs that juxtaposes images of decommissioned weapons and missiles in the National Atomic Museum in Albuquerque, New Mexico, including a duplicate of the bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki in World War II, with ancient Native American Petrogylphs on Southwestern cliffs and boulders. Seeing the painted figures, he felt connected to “the human minds and beings that had made these drawings long ago. Protected only by falcons and owls and by a remoteness not yet breached by vandals, these stoic figures appeared to symbolize the very birth of civilization.” With this work, he felt compelled to pair the origins with human civilization with the very means by which it could be entirely destroyed.

Another dimension of John Pfahl’s work is illustrated by series such as Permutations on the Picturesque (1993-1999), which took him to the British Isles and Italy in search of what remained of the places described in the “marvelous book, The Search for the Picturesque, by Malcolm Andrews,” that he described as “a revelation.” He found the ruins of Tintern Abbey Exterior, River Wye, South Wales (1993/1997) were almost exactly as drawn by Sir John Herschel in 1829 using a camera lucida. John set his camera to capture the fog engulfed façade and added the mark of 20th-century technology with pixilation in the lower portion of the print.

A few years earlier, for Arcadia Revisited: Niagara River and Falls from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario (1985-1986), John traced the route Amos W. Sangster (1883-1904) documented in his portfolio of 153 etchings (1886-1888) that captured the waterfront of Western New York as an awe-inspiring natural phenomenon on the cusp of its being harnessed for industrialization of electricity. The centennial reflection was his way to use “the art of photography to research the ways in which the pictorial strategies of the Nineteenth Century color the way in which the American landscape is apprehended by today's viewers.” While paying homage to “the aesthetic legacy of the past,” he used his own gift of composing “to confront the changes wrought by superhighways, dams, nuclear plants, and urban sprawl….” The resulting traveling exhibition paired Sangster’s and Pfahl’s images for maximum effect.

Transcendentalism, a philosophical aesthetic movement epitomized by 19th-century authors Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, also permeated John’s photography, as it did for Charles E. Burchfield. They had in common a reverence for the land, which you can see in John’s homage to Burchfield—ethereal white sunlight glowing through altocumulus clouds directly over a manmade pyramid of rich, frozen earth in Nursery Topsoil Pile (Winter), Lancaster, New York, February 1994, from the series, Piles. That grounding in transcendentalism can also be seen in later series. The stretched, purposely distorted images of his Scrolls series of 2006 are reminiscent of centuries-old Chinese landscape paintings (which also influenced Burchfield when he was a student at the Cleveland School of Art). In Dark Cathedral, a vast sunset sky stretches vertically over a miniscule blackened horizon of indistinguishable elements fronted by glistening water. The technologically stretched dark shapes yearning upwards, atmospheric glow, and clouds shifting from a warm register to cooler blues and violets transform what might have been a mundane site into a “dark cathedral,” imbued with a mystical, spiritual quality.

John’s ability to draw inspiration from different disciplines kept him and his art vibrant. One of the last times I saw him was when he came to the museum for Geography Professor Stephen Vermette’s presentation, “The ‘Nature Paintings’ of Alexander von Humboldt: His Revolutionary Use of Art to Reveal Scientific Concepts,” celebrating the 250th anniversary of the birth of this “towering figure in the natural sciences.” Genius attracts genius. There is so much more that could be said, and this is just a sample of how awed I have always been in the presence of John Pfahl and his photography. He was never static; always exploring new strategies and techniques. His creative genius will be missed, but we will savor all the art he created to make our lives meaningful.

—Nancy Weekly, Burchfield Scholar, Head of Collections & Charles Cary Rumsey Curator, April 22, 2020