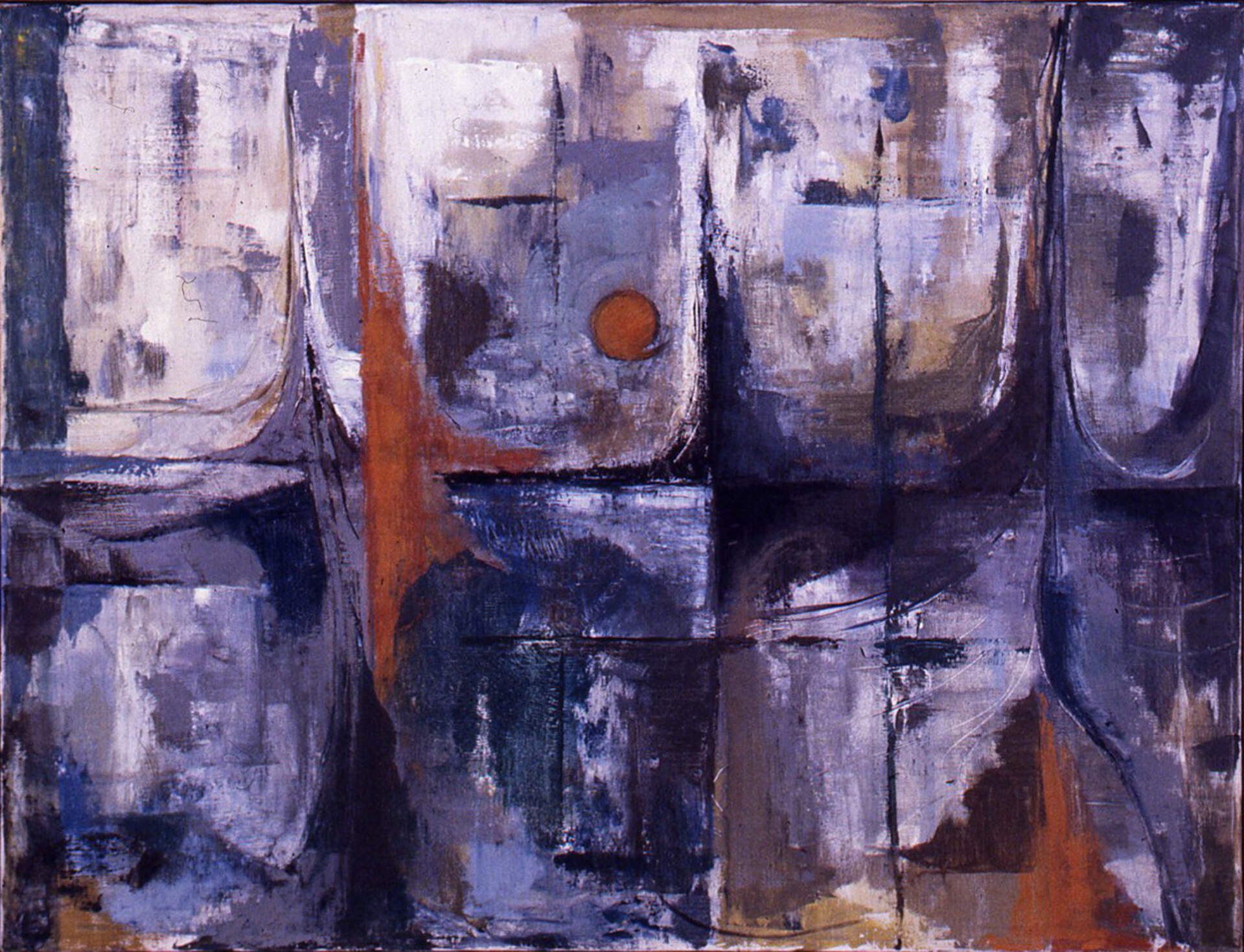

Cravens, Annette M. (1923-2017), Night Reflections, 1953; oil on canvas, 32 x 24 inches; Gift of the artist, 1989

Remembering Annette Cravens

Sunday, Feb 5, 2017

The landscape of the cultural community of Western New York has changed. That is what continually happens, evolution is the continuance of living. Annette Cravens (1923-2017) was part of a lineage of philanthropic and community engagement that includes generations – her mother Mildred McGuire Lockwood Lacey and father Edgar McGuire, the successor of Roswell Park, and stepfather Thomas Lockwood, names known to all those involved with the State University of New York at Buffalo and the entire community of Buffalo.

Annette traveled the world collecting art and artifacts and too many people might have only known her through these objects. There is no doubt that the things that she acquired represented a very clear eye to aesthetic values honed thoughtfully over a lifetime.

Many people may not be aware of Annette’s concerns beyond objects. From the time she graduated from Sarah Lawrence College in 1945, she maintained a concern for people, particularly the disadvantaged. After graduation, she worked in New York at the East Side House Settlement, before returning to Buffalo. After World War II, in 1949, she married DuVal Cravens and later went on to get her Master of Social Work from the University at Buffalo. For a time, she also worked at Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo.

Even those who did not know Annette well might have seen her at every event and many performances in the community. Known for her rigorous responses to artistic production, she held an opinion on all things. This was clarified for me once, when I asked her, “If you dislike this (whatever it was at the moment), why do you bother going out to see it?” She responded with a statement that should be a model for all people who stay at home pre-judging things. Annette said, “I may know in advance that I will not like something, but if I do not go and see it, how can I be sure.” This was how she lived her life, as a participant in culture, from the visual arts to Neglia Ballet to Torn Space Theater and many others; she cared most when people were trying.

The visual arts organizations were probably the most aware of Annette’s presence, as a supporter and frequent attendee of, the Burchfield Penney Art Center, the UB Galleries (with a focus on Anderson Gallery) and the Albright Knox. She was just as likely, though, to arrive early at gallery openings for events like Allentown’s First Fridays. As she amassed a significant collection ranging from antiquities to contemporary works, Some might assume there was some clear thought that she had when selecting the objects she collected. This, however, was varied, and she was always a student. She would purchase artwork for a variety of reasons – to support an artist that she felt needed the encouragement; or because she was not sure of whether or not she would like something and knew that she wanted to ‘live with it for a while’ to see if it was any good; and certainly because a work had an immediate impact on her.

Along with her willingness to share her thoughts, it was her constant consideration about the world that made Annette special. Many might have assumed, after a particularly harsh criticism, that she was rushing to judgment or just did not understand something. This was not true. Annette never made comments inspired by any meanness and her aesthetic values may not have aligned with popularity. Her feelings were not personal, and she did not hold one experience against an organization or individual. She offered her opinions, and then eagerly arrived at the next opportunity to experience the person or place again, as soon as she was able. Those that were unable to absorb her opinions (right or wrong) missed something crucial. She knew that if all she ever said was that something was good, as so many of us tend to, neither the maker nor the audience would ever grow. No one would know this more than those that she loved, because they were the ones for whom she held the most interest in being the better.

Few people know that in addition to supporting the arts, she also made paintings. She did not spare herself from the kind of critique she had for others. She recognized in the limited production she had in painting that she was not going to be the kind of artist that continued on in the gallery tradition. However, she did recognize the value in trying to make work. As recently as four years ago, having not painted in decades, she thought about making work. Not because there was something of great genius she thought she could create, but that she knew she wanted the challenge of pushing paint around and to suffer from the challenge of making something.

The lasting impacts and challenges that Annette has left our community, through her support and sharing of collections, is one that she always stated in a short poetic form. She wanted people to look and to see. She wanted to be a teacher to the end, but not the systematic form familiar to contemporary education systems. She believed that there exists an intrinsic beauty, and if people could just learn to see, they would know. This was not a beauty established by some market or of some fiscal value. It could range from the perfectly thrown pot, to a painting, to a tree, or to the way an individual stands among others. She felt that if we just presented things (in proper arrangement, of course), people would know, and through continued exposure and engagement we would learn. She believed that this, our ability to question and to learn, was something that all people could share.

—Scott Propeack, associate director/chief curator