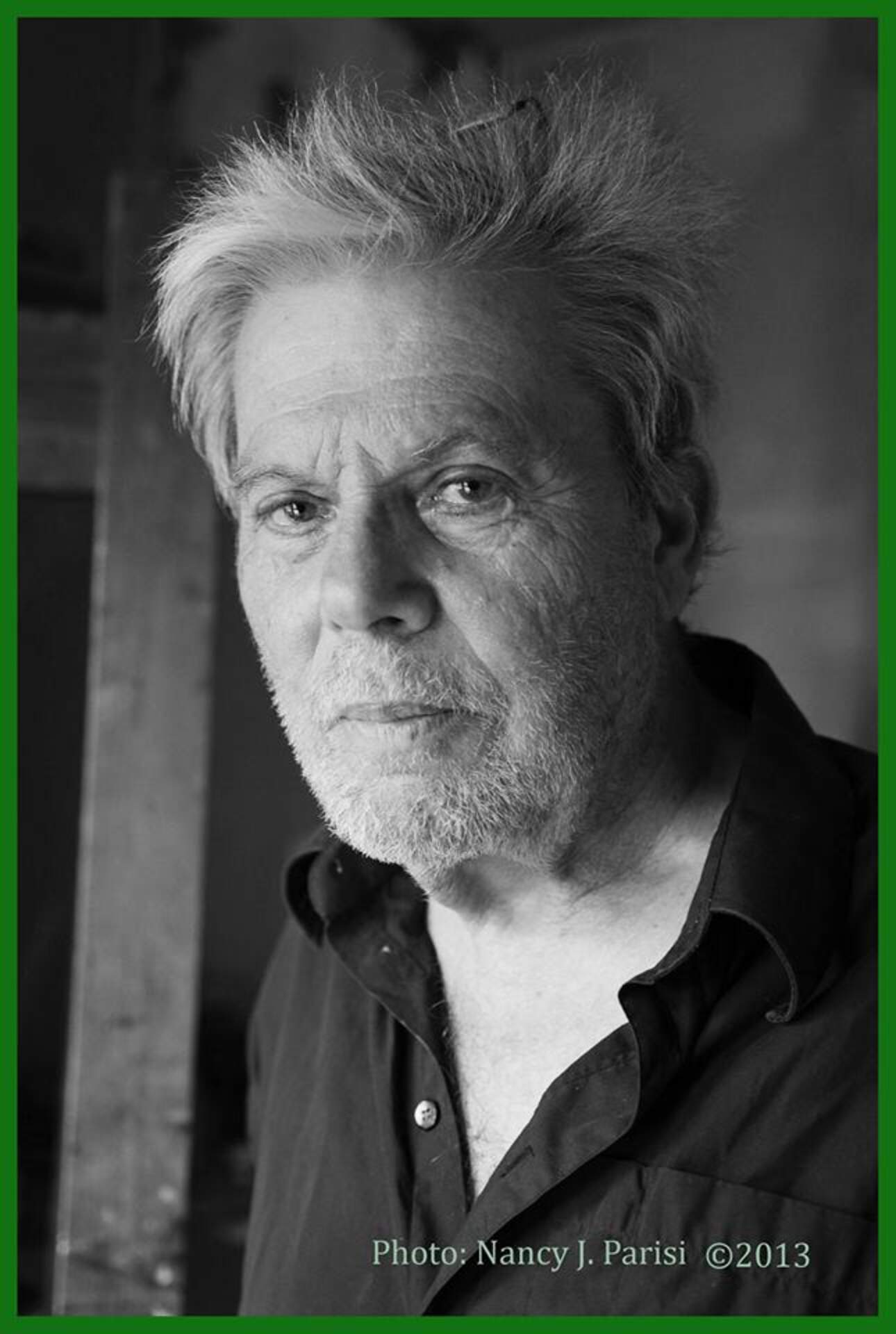

Bruce Kurland by Nancy J. Parisi

Bruce Kurland: Handfuls of Memories and The Cosmic Slap by Nancy J. Parisi

Saturday, Jan 25, 2014

We're reeling through an endless fall.

We are the ever-living ghost of what once was.

- Band of Horses, from No One's Gonna Love You

To the best of my memory it was in the half-dark, fully-hazed light of a barroom (The Old Pink, specifically – probably after an art opening, to class up the story) where I met Bruce.

Everyone asks me where I met Bruce: my recently-escaped mentor.

From there it would become a bond with nearly a quarter-century of openings, conversation over meals, walks in Nature, walks through malls (his idea), dancing in the dark and mind-bogglingly loud corners of The Continental, day trips to Toronto where Brucey could once again “be Chinese,” and countless parties.

He was my first and best cooking partner: our kitchen slogan (pardon my French) was “We don’t fuck around!” We cooked up Thanksgiving dinners for 20 or so efficiently, Bruce stationed by the oven to baste the turkey, to tent it with foil at the right time. As with everything, it was done with precision.

Sidenote: anyone who ever sat at his table knows what a great cook he was. His Bambi stew, as he called it, was incredible, and the ritual of his potato pancake feasts included him regaling all - as his mother had, he said - with a recounting, humorously, of course, of the toll the grating of the bag of potatoes had taken on his knuckles, holding them up for effect.

That night, in the Old Pink in the early 90s, there was raucous laughter, talk of Art, and a promise to meet up again in the near future.

I was there with a fellow artist, my boyfriend at the time. We were young and in the midst of what adults fondly refer to as salad days, and my boyfriend and I thought that we had just met our sugar daddy: Bruce was fresh from New York, back in Buffalo with the whiff of success, and the unknown, and confidence about him.

The boyfriend left Buffalo and Bruce and I remained constant friends. Bruce would meet other boyfriends, I’d always call him as soon as possible after an introductory dinner.

Well, what did you think, I’d ask. And he would deliver a fair, uncompromised, assessment. He was a great judge of character. And he was usually always kind.

And spot on.

We brought out, in many ways, the best in each other –he was a person to distill current events with, someone to discuss Art. He was an empathetic ear after fiascoes. After a trip to the hospital after being crashed into by a drunk driver downtown, and sitting up all night instead of sleeping in case I had a concussion I called Bruce at dawn’s first light, knowing he’d be up. I thought we would have a laugh, but instead Bruce said ‘I’ll be right over.’ He was that type of friend.

As with close friends and family there was retelling stories again and again to the same explosive laughter. One of our favorite retellings was of the burnt parka incident.

After a day of being Chinese in Toronto we ate at a favorite restaurant and after dinner smoked at the bar.

Suddenly there was a strange burning smell.

I realized it was coming from Bruce’s favorite parka (a classic navy blue with bright orange interior and faux fur trim around the hood), which he wore from November until April…it was on top of a votive candle on the bar.

I picked it up and saw the parka’s faux fur smoldering so I waved it frantically, making it all much worse.

We laughed all the way back to Buffalo.

I bought him a new parka, but he preferred to wear his other parka with the melt hole in it.

Which reminds me of how I implored him to get a cell phone in case of emergency when he was out on the Wiscoy, or the Lake.

What if you’re going through the ice, I asked.

I’d want you to call me.

So he got a cell phone.

And one day when he was in Wyoming County I tried to reach him – to no avail.

When we did meet up later I asked if he had had his cell phone with him.

Yes, he said, but I keep it locked in the trunk of the car.

When he was in the hospital for an extended time I leant him a laptop and we set up an email account for him.

I bookmarked sites I thought he’d like: Art in America, The New York Times, etc.

His first email, to me, had “Your upcoming show at the Whitney” in its subject line. The email was once sentence.

The next day, when I went to see him at the hospital, the laptop was closed and off.

I prefer talking to people on the phone, he said, I don’t like emailing.

Bruce was a great and loyal friend to many, his little black phone book teeming with those he’d known his 75 years.

Well, most of those he’d known.

When, years ago, I told him that I thought of him as my third parent he immediately let me know that he did not care for that designation.

What would you prefer to be called then, I asked.

Your partner in crime, he said.

And so that stood.

But secretly I still called him my third parent.

To speak with Bruce about Art was to be imbued in a world where Art swirled into Life: it mattered, it was part of everything.

Names that you had read about or studied (and many you would look up later and remember) were foremost in the midst of his impressively vast intellect. They were schoolmates of his at Art Students League, or who he had shown with, or who he had argued with, or for whom he had a reverence.

We spoke at length of images and qualities of light by artists that we loved – countless renderers of light.

We debated at length over the years about light, and how photographers and painters speak of light differently.

Bruce called me a technician, as I work with a machine.

When I was younger I bristled at this, but of course he is correct.

To make his work he had brushes that he’d customize by taking a razor to their tips, precise pigments, and board he’d labor over to prepare for the paint.

His work was not just of the collected objects before him, but of his relationship to them, and the fleeting emotion that he was capturing: awe, reverence, horror, love.

When he was working on a painting you would hear occasionally of its components: the package of meat, the skull, the cupcakes, the dried squid.

They were like his house guests, or intriguing correspondents. They entered conversation, you saw them in the studio and on the panel.

You would learn with Bruce to not ask about the work, to let him speak first about the work in progress.

I would sometimes see these pieces in-situ/progress and they always took my breath away.

It was magic. They were personal. Always with the essence of purity of vision, an artifact that fell from the sky or was discovered propped up in a secret cave.

At a dinner one evening I mentioned one of his paintings that I especially loved, that was underway–his response was of surprise. Surprise that it was recollected, or that it existed already and independently in its incomplete state.

To him I think that he thought of all his work as incomplete, to all of us others they are masterpieces.

Once I said how much I loved a painting and described it to him, as there were several in the studio awaiting their time.

Apples, a big green swoosh over them, I said, gesturing in the air.

Oh, that painting, it’s been wiped out, he said casually.

I quietly mourned that image that I had seen. I wondered then how many paintings had been unpainted. He told me that collectors would sometimes have very different paintings returned to them after he spent some time with his older work that he would convince them needed a bit of reworking.

He was always refining, always learning, always reading, always reaching.

The painting of his that I own he referred to as “The Unloved Painting,” I’m its third owner. It’s a flayed sheep head, a slice of raw beef, a curtain of ruined and graffiti-strewn wood behind the objects.

Last winter Bruce borrowed one of my digital cameras to drive into the landscape that he adored south of the city to document fields and the quality of the blue snowy light.

We looked at these images together, and I made prints for him to study.

In the summer of 2012 he asked me to make portraits of him in his studio for him to make a self-portrait, which Toni now has, an unfinished work. One of those images is on your program cover.

Bruce never said he could not do something, he never let his physical changes or challenges over the last few years stop him from country jaunts, or recovering enough to drive himself to the places that he loved.

On a recent wintry drive of my own I had a revelation that has brought me much peace: Bruce is now on a cellular level, he’s in me, his influence is great. I know that he’d like that statement.

I was lucky to have one of his final conversations on the night of December 9th. As he lay in his bed he asked about others, and how I was doing.

He said “All you can hope for is to be happy.”

On the 11th, the night he died, I believe as he made his way to the good light, Bruce’s voice was strong in my ears, ordering me to

“Live, live, live."

Nancy J. Parisi is a photographer living in Buffalo and dear friend to Bruce Kurland