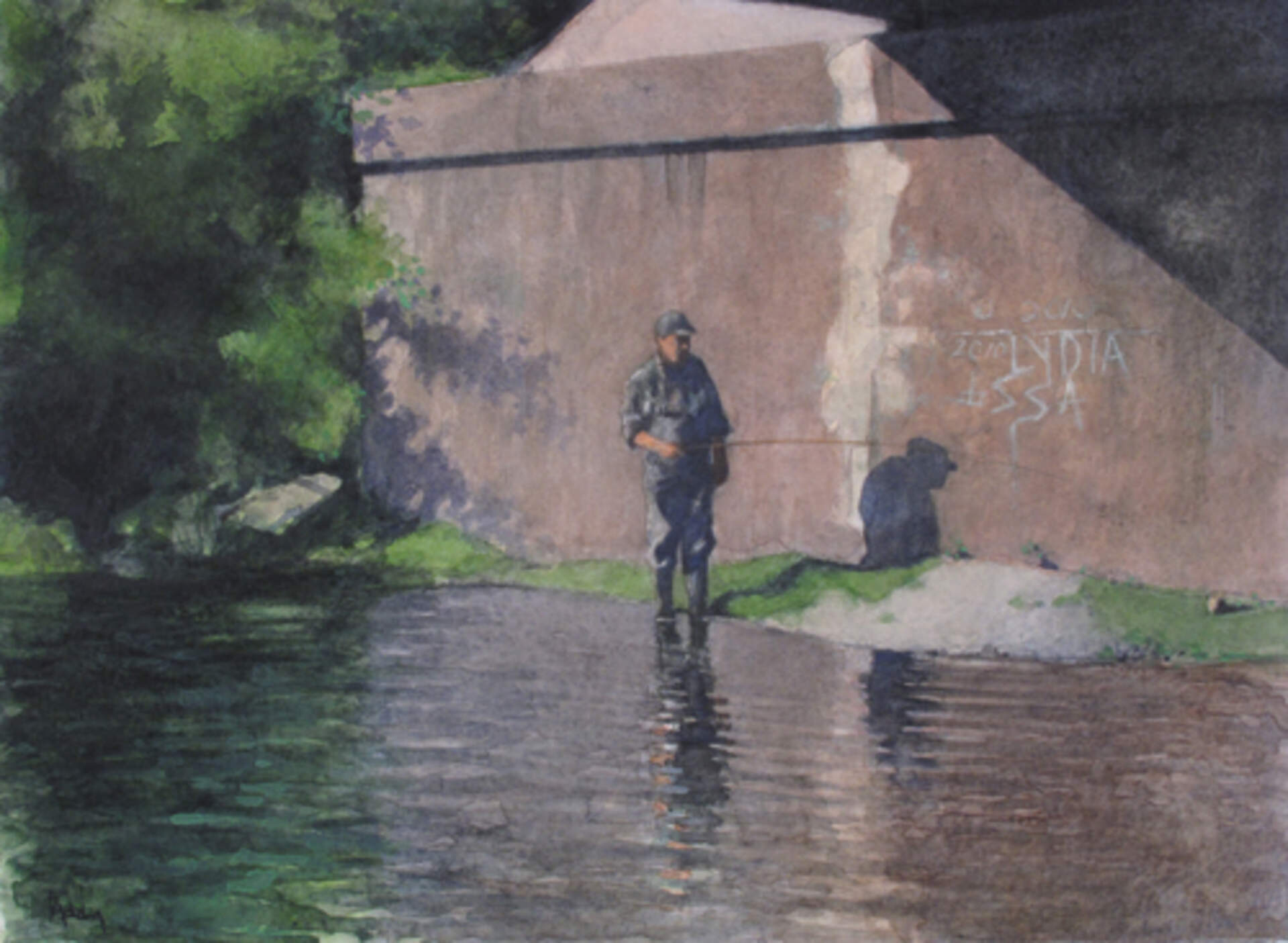

Thomas Aquinas Daly b. 1937, BK Fishing Downstream, 2012; watercolor on paper, 11 1/8 x 15 ¼ inches; Courtesy of the Artist

Thomas Aquinas Daly Remembers Bruce Kurland

Wednesday, Jan 22, 2014

It was 1969, and I took the day off work to go trout fishing on Spring Creek in Caledonia. Walking down the railroad tracks with my rod, I stopped on the trestle to get an overview of the stream. A solitary fisherman was in the first pool. I watched for a while to see if he was catching anything. Though I was hesitant to interrupt his fishing, I asked how it was going. That's how our 44 year conversation began.

I learned right away that Bruce was a painter, and that he actually made a living selling art. This boggled my mind. At that time he was living in an old farmhouse in Curriers with his wife Toni and three little daughters. Fresh from New York, his work was attracting the interest of local collectors and he was enjoying a comfortable income.

Bruce soon became my mentor, albeit a reluctant one. I drove him nuts. Occasionally he would cave to my relentless badgering and offer up a nugget. It was always profound. He was a limitless font of information, sharing things I never learned in art school or read in books. He patiently explained that there were basic rules that a representational painter had to learn before earning the license to break them.

First and foremost, he told me that I had to learn how to see. Forget the paint and the brushes. It was all about processing information. Nobody did it better than Bruce. Most of his time was spent staring at his work through a haze of cigarette smoke, transfixed, working out the puzzle. His paintings weren't accidents.

"You have to paint a thousand pictures."

I got busy. He taught me the differences between indoor and outdoor light. We worked on my paint quality. I had to learn to solve problems in a painterly way. As an exercise, he instructed me to make small pictures with a big brush.

"Get your picture any way you can."

I began doing all sorts of unorthodox things with my watercolors...things that would send purists screaming into the streets. It worked. (To this point: My son recently asked Bruce how he achieved the rich background surfaces of his still life paintings. He told Jon not be afraid to drop his paintings on the floor of a city bus and let them get kicked around.)

On his way to New York City in 1980, Bruce directed me to stuff my little watercolors (I was still diligently working my way toward that goal of 1000) into a manilla envelope and he would "show them to some people." That single gesture changed my life. Within days, the director of Grand Central Art Gallery contacted me and I was on a flight to New York.

Bruce and I shared a lot of interests beyond painting. We both grew up with an insatiable need to know wild things. It was never enough to passively watch them from afar. We had to hold them in our hands, feel their warmth, examine their feathers, fur and scales. Birds, insects, plants, fish and mammals populated our still life paintings as well as our freezers. Occasionally we traveled to fish in Newfoundland, Michigan, or Pennsylvania, but what we truly loved was right here in our back yard.

For several years, after the summer residents vacated their cottages on Abino Bay, we crossed the Peace Bridge into Canada almost daily to hunt ducks. We taught ourselves how to carve decoys. Bruce's innate genius for form served us well; his decoys were beautiful. We worked on building a boat exclusively designed for our esoteric method of duck hunting. Together we experienced Lake Erie in all its beauty and rage. Our ultimate adventure occurred in 1975 when we got caught out in the storm that sank the Edmund Fitzgerald.

During winter we went ice fishing on Silver, Conesus and Honeoye Lakes. Fall found us hunting geese and ducks in the corn fields of Wyoming County or deer in Letchworth State Park. Right up until the end of Bruce's life, we were still fly fishing for trout on Spring and Wiscoy Creeks.

Bruce's former wife recently observed that we were a lot like brothers. We would argue, get fed up, and part ways. After a cooling down period, we would pick right up where we left off, doubled over in laughter. Though he would drift off to other places for a few years at a time, he always found his way back here to Western New York. This was his home.

Thomas Aquinas Daly's poetic landscape and still life paintings embody themes of land and nature. His oils and watercolors have been featured in galleries, museums and universities throughout the country. A lifelong resident of Western New York, he currently lives and works in Wyoming County.