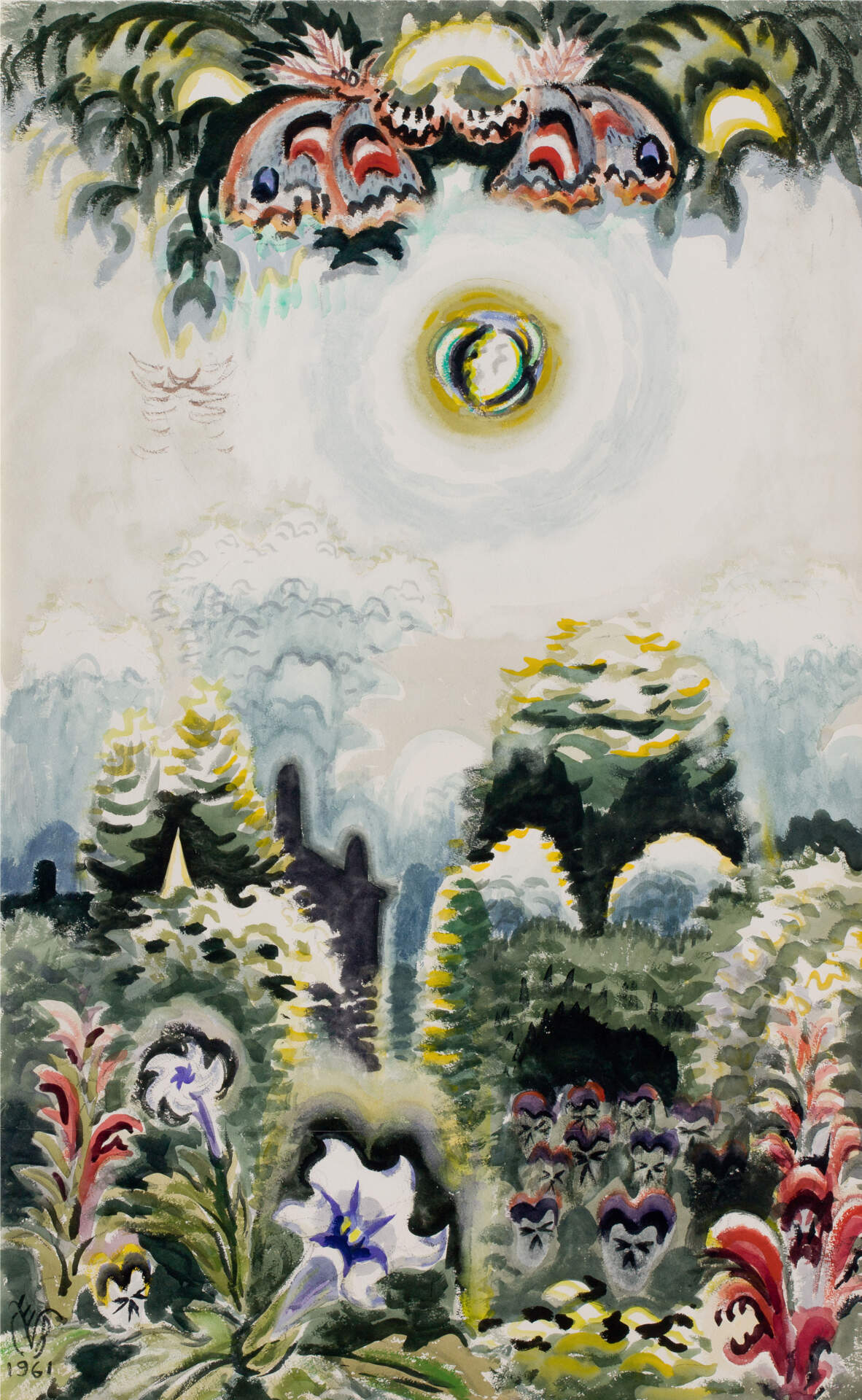

Charles Ephraim Burchfield (1893-1967), Moonlight in a Flower Garden, 1961, watercolor and charcoal on joined paper, 48 x 30 in. (121.9 x 76.2 cm.), Young Sloan Collection

A Vast, Tiny World

Burchfield's Insects & Spiders

Upcoming

May 8, 2026 - Aug 30, 2026

Did you ever imagine, with childhood wonder, being so tiny you could live among flowers as tall as trees and converse with critters, once nearly invisible, now the size of companions? Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, one of Charles Burchfield’s favorite books, portrays an anthropomorphic fantasy that materializes, in essence, in many of his paintings and drawings. Plants and trees seem to have human emotions and traits. Floral aromas perfume the air so pungently that he even believed trees could smell their scent. Insects and spiders that live often hidden in the landscape are exaggerated in scale to give them agency. Their flight and sound patterns become visible, animated within single images, literally bringing energy to the forefront.

In Burchfield’s art, oversized cicadas rattle metallically, hidden crickets fiddle in the grass, katydids creak their names, and mosquitoes hum and sting maddeningly. Colorful Monarch and Swallowtail Butterflies flutter in airy arabesques and inhabit dreams. Intriguing Cecropia Moths provide an air of mystery to summer nights. Dragonflies dart back and forth over a stream strewn with pond lilies. He declares, “The most beautiful things of the evening are the fireflies.” In the arachnid world, golden-orb spiders weave glistening webs that capture “drops of sunlight” that glide on the gossamer. These windows on a microcosmic world guide us to appreciate a world for which many of us are blind. But the more we learn, the more exciting it becomes.

Artworks in this exhibition, curated by Burchfield Scholar Nancy Weekly, are drawn from the Burchfield Penney Art Center’s substantial art collection and archives, and lent from private collections. They offer a glimpse into the artist’s inclusion of some of the smallest creatures that are part of the immense ecosystem we inhabit. Through his inventive means of expressing his own sensations while scrutinizing, listening, and smelling inspirational landscape scenes, we come to appreciate the fullness of shared experiences. He is our nature guide.

The Buffalo Museum of Science will share some of their resources so we can compare scientific specimens with artistically conceived representations. In addition, a few works by Western New York artists provide different views of similar subjects and soundtracks of distinctive "insect songs" add to the verisimilitude and learning opportunities. The Education Department plans to offer a workshop on drawing "doodle-bugs" based on Burchfield's doodles created by mirroring names written in script. A small publication will document this unusual subject.