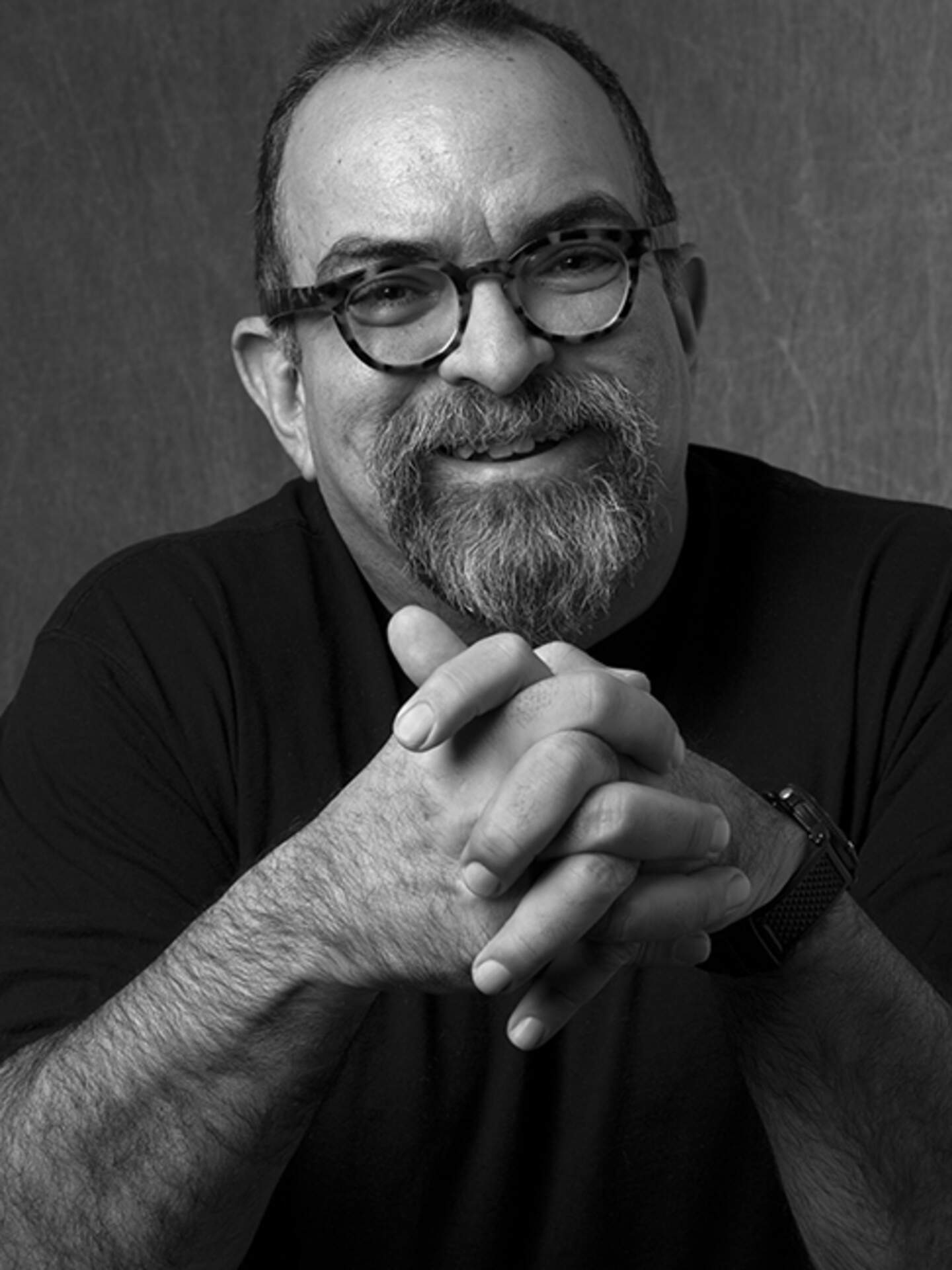

David Moog (b. 1944), Alberto Rey, 2015; Archival inkjet print, 20 x 15 inches; Gift of the artist, copyright David Moog, 2015

Artists Seen in The Public

Thursday, Sep 3, 2015

More at http://www.dailypublic.com/articles/09012015/portrait-artist

“The seer and the seen are indistinguishable.” —J. Krishnamurti

Along one wall of one of the project rooms at the Burchfield Penney, two rows of handsome black-and-white photo portraits of the artists. A different sort of project for photographer David Moog, who has not previously done portrait photography. On the other side of the room, one of his photos in his more usual manner, of rocks—boulders—and ferns poking out among them.

The project, to photograph as many of the working artists in Western New York of the present era as will come in and sit for him in his ad hoc photographic studio. The present era being as long as it takes to complete the project, several years possibly. But an archive for some distant future era, maybe centuries hence. These are the artists—this group, this collective—that made the art that was made in Western New York in the first part of the 21st century. When likely no one will remember many or possibly any of them individually. Because although art is said to be long—versus life, which is well known to be short—the greater truth is that all things pass.

How to talk more about this project? Not easy to do. Not because Moog won’t talk about it. He talks volubly and at length. But in an overtly Buddha dharma manner. Talk that is consistently interesting and often enlightening, but not always easy to follow. That rejects terms and concepts—pretty much rejects the concept of concepts—the way we regularly employ them. The way we regularly talk about portraits. For example, we regularly say about portraits—ones we particularly like—that they capture the essence of the subject. Or something of the essence, something of the soul. Moog rejects this sort of talk out of hand. Rejects the term “essence.” What is it? But even the term “capture.” An aggressive term. Not what he does when he does photography. Rejects or questions even “like.” What does it mean?

But how capture the essence—in the rejected terminology for the moment—of something as complex as a personal subject in the maybe thousandth of a second of the camera’s operation?

How Moog describes the process or event—the photographic recording of an image—is as a “transcendent moment” between the photographer and the subject. (If it happens. If it’s transcendent. Something like with grace. No guarantee of it, but you can work at it.) And the produced image—the photo—opens the possibility of a second transcendent moment, between the viewer and the photo. That may—the transcendent moment between the viewer and the photo—be somehow “equivalent” to the transcendent moment between the photographer and subject. A word and concept—equivalent—of pathfinder modernist photographer Alfred Stieglitz, one of Moog’s spiritual mentors.

An actual mentor—Moog studied with him, formally and informally, through most of the 1960s—and also major figure in the history of photography that he refers to frequently in talking about his own work is Minor White. White said photos are questions for the photographer. He said photos are koans.

On the equivalence idea, White said, “One should not only photograph things for what they are but for what else they are.”

(Considering all of which—the Buddha dharma thematic, the equivalence matter—one comes to perceive the photo of the rocks and single sprig of fern as a kind of capsule image of Zen meditation garden. Equivalent.)

So what is the difference between the rocks and fern photo on the one wall, and the portrait photos on the other?

Talking about the rocks and fern photo—and in general the kind of photography he has always done previously—Moog said, “I try to see into the nature of things, and in making a photographic image, I become part of that nature.” Afterwards he revised this formulation. “Not try,” he said. “Buddhists don’t try. Someone who tries to be virtuous can never be virtuous. Either we are or we’re not. We do or we don’t.”

Whereas, about the portraits—and this seems to relate to why he rejects the notion that these photos in any way capture essence, though he rejects the notion in general that portrait photos capture essence—as the photographer, he says, “I am a window.”

Open for discussion. Meanwhile, he says, artists of whatever stripe—painters, sculptors, photographers, musicians, even writers—should email him at david.moog.images@gmail.com or project curator Scott Propeak at propeasf@buffalostate.edu to make an appointment to come in to the Burchfield Penney to be photographed. If you make art—and you don’t have to have won prizes for it—you don’t have to be a Picasso or a Matisse—you need to be in the archive.

To make an appointment, call 716-878-6011 during gallery hours.