Charles E. Burchfield

Art

One of America’s most original artists.

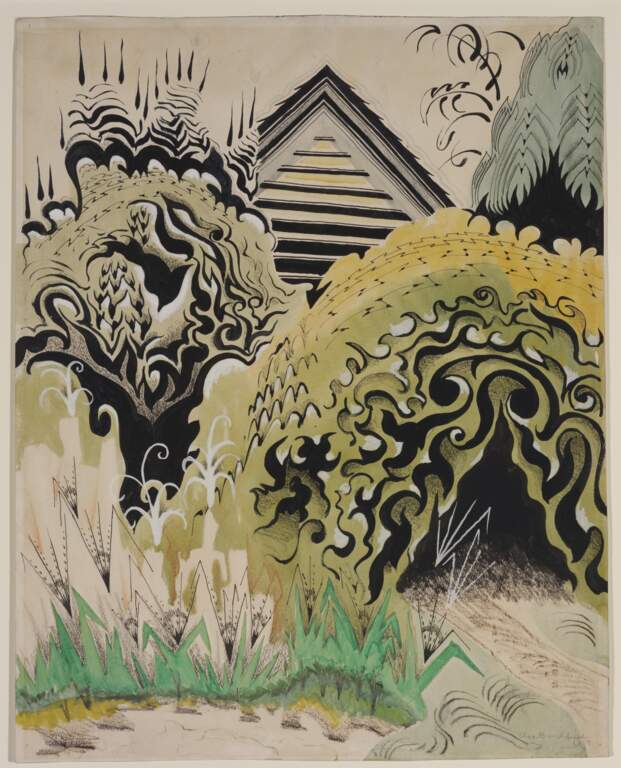

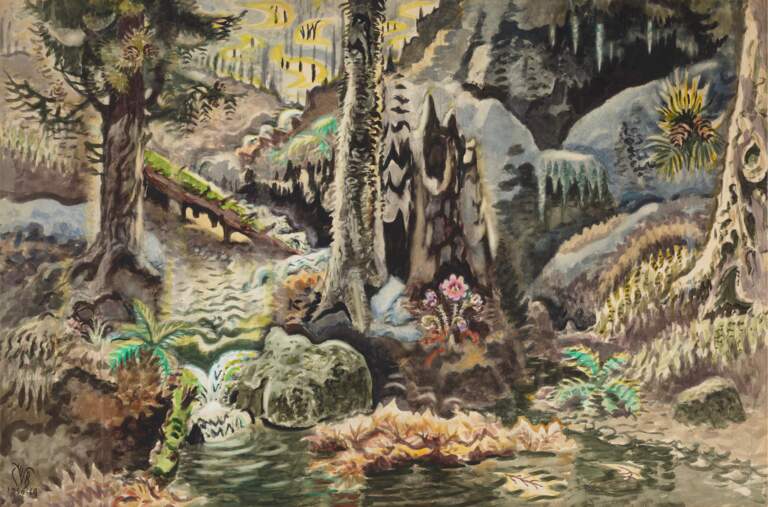

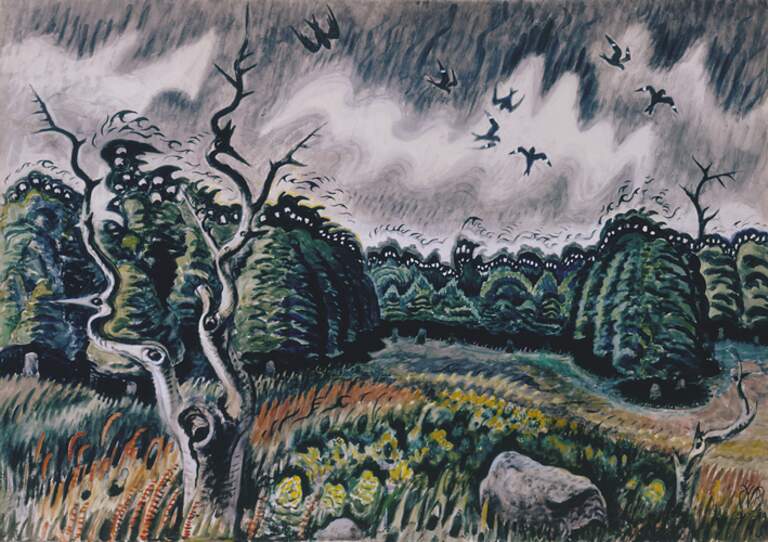

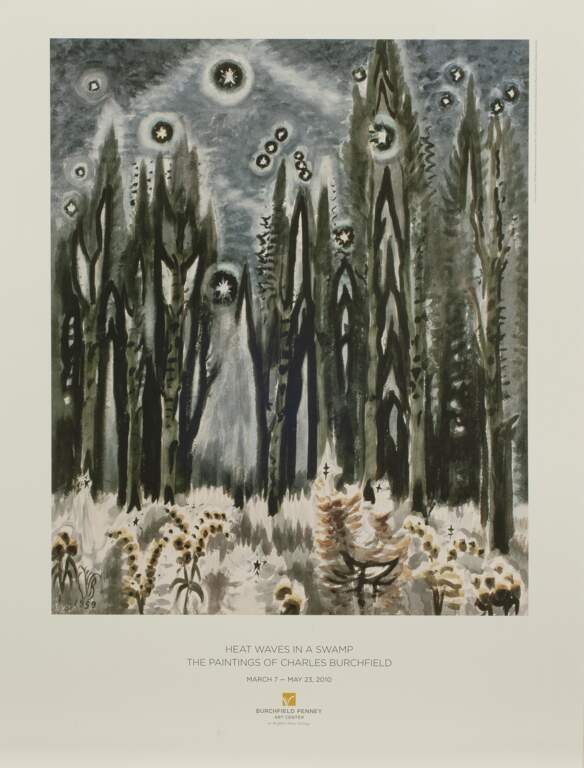

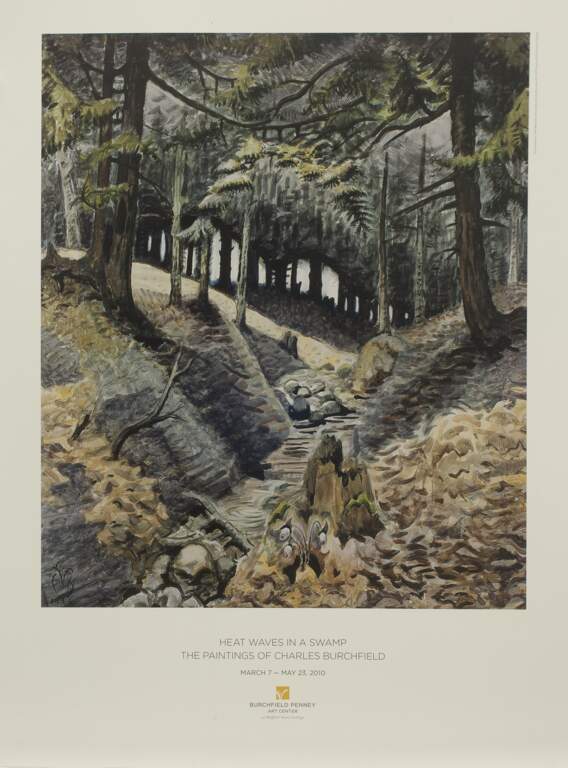

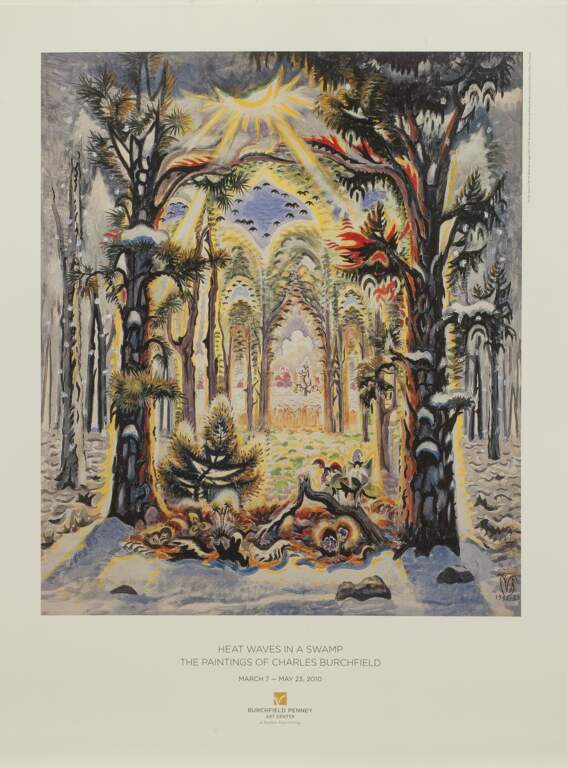

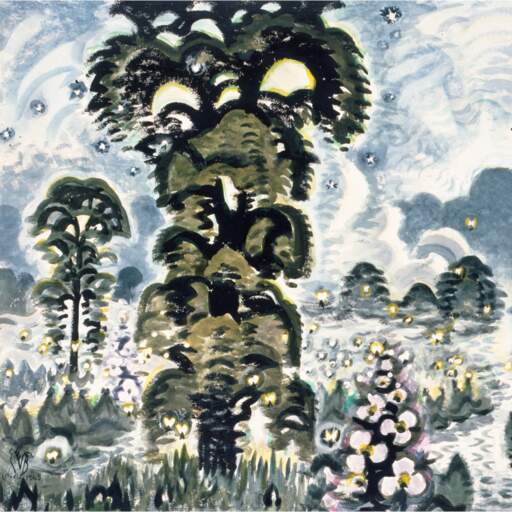

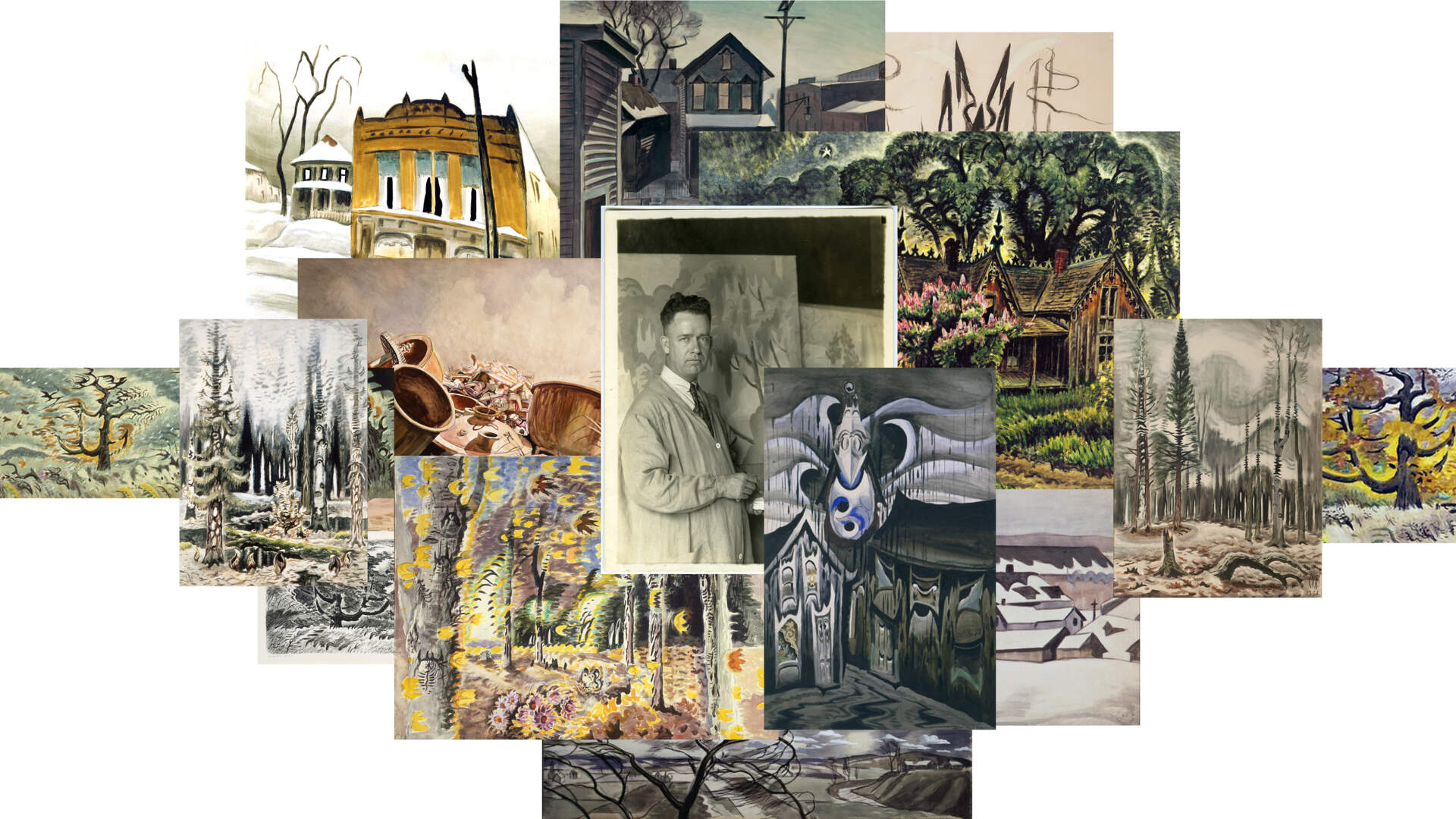

Best known for his romantic, often fantastic depictions of nature, watercolorist Charles Ephraim Burchfield (1893–1967) developed a unique style of watercolor painting that reflected distinctly American subjects and his profound respect for nature.

The Burchfield Penney Art Center features the largest collection of works by Burchfield. Within the intertwined galleries of the museum, you will find an ever-changing display of his paintings and sketches, a re-creation of his studio, the Charles E. Burchfield Rotunda (specifically designed to highlight his seasonal works), and even references to Burchfield in the building's architecture.

Explore Burchfield's Paintings

Gallery

Life

An artist to America.

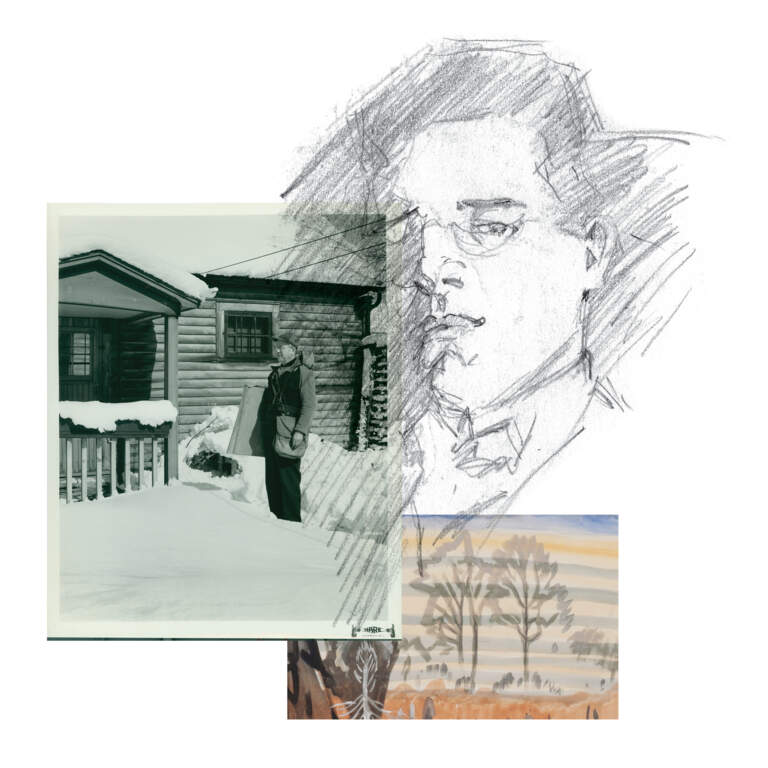

Charles Ephraim Burchfield (1893–1967) was an American painter, best known for his watercolor landscapes. Burchfield was born April 9, 1893, in Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio. Five years later, his family moved to Salem, Ohio, where he graduated from high school as class valedictorian in 1911. He attended the Cleveland School of Art from 1912 to 1916 and studied with Henry G. Keller, Frank N. Wilcox, and William J. Eastman.

In 1921, Burchfield moved to Buffalo, New York, to work as a designer for the prominent wallpaper company, M.H. Birge & Sons Company. The next year he married Bertha Kenreich, with whom he raised five children. Fascinated by Buffalo's streets, harbor, railroad yards, and surrounding countryside, he adopted a more realistic artistic style. Burchfield's foray into realism lasted for several years.

He became friends with Edward Hopper in 1928, after Hopper’s essay on Burchfield appeared in the July issue of Arts magazine. Hopper wrote, "The work of Charles Burchfield is most decidedly founded, not on art, but on life, and the life that he knows and loves best.”

Download PDF Timeline of Burchfield's Life

In 1929, the Frank K. M. Rehn Galleries in New York City began representing Burchfield, allowing the artist to resign from his job as a designer to paint full-time. During this period, his works show optimism and an appreciation of American life. In 1930, his work was the subject of the Museum of Modern Art in New York’s first one-person exhibition, Charles Burchfield: Early Watercolors 1916–1918. He was included in the Carnegie Institute’s the 1935 International Exhibition of Paintings, in which his painting The Shed in the Swamp (1933-1934) was awarded second prize. In December 1936 Life magazine declared him one of America’s ten greatest painters in its article "Burchfield’s America."

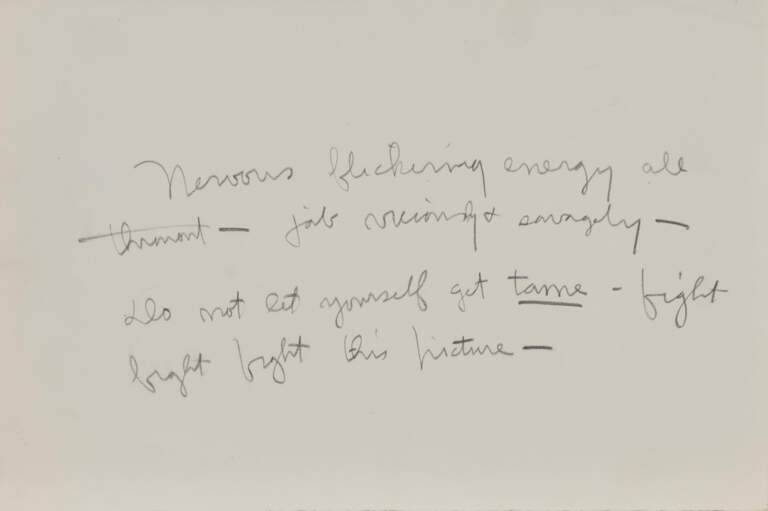

In the 1940s, Burchfield returned to ideas begun in early fantasy scenes that he often expanded into transcendental landscapes. Burchfield, always probing the mysteries of nature in an attempt to reveal his inner emotions, once stated, "An artist must paint not what he sees in nature, but what is there. To do so he must invent symbols, which, if properly used, make his work seem even more real than what is in front of him." He followed this artistic vision until the end of his life, creating some of his most mystical works.

Burchfield’s artistic achievement was honored with the creation of the Charles Burchfield Center at Buffalo State College on December 9, 1966, a month before his death on January 11, 1967. Today, the Burchfield Penney Art Center stands as a testament to the art and vision of Charles Burchfield and the artists of Western New York, and the museum holds the largest collection of works by Burchfield as well as more than 70 volumes of handwritten journals, 25,000 drawings and other ephemera including a scale re-creation of the artist’s Gardenville, New York, studio.

President Lyndon B. Johnson eulogized the artist in a letter dated November 14, 1967. President Johnson wrote, "He [Burchfield] was artist to America."

Words

More than 10,000 handwritten pages.

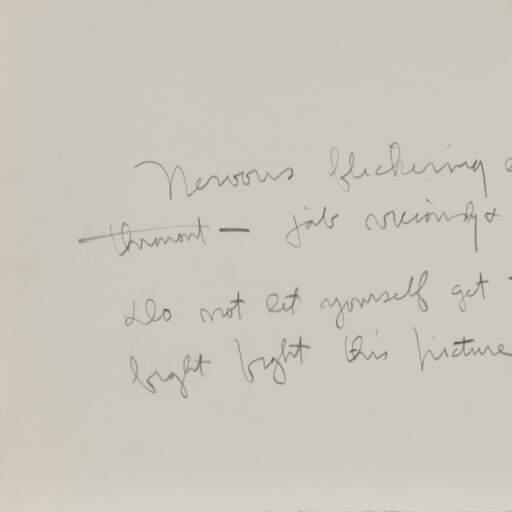

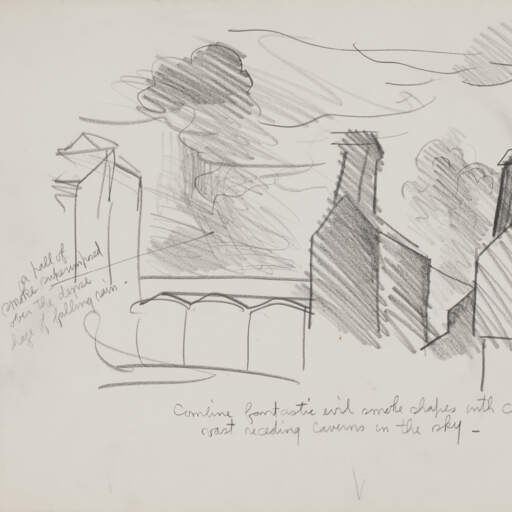

From the age of seventeen until the end of his life, American watercolor painter Charles E. Burchfield wrote in journals that chronicled his artistic and intellectual development. These journals reveal much about his unique vision, love of nature, and gift for writing. Burchfield’s passion for writing could not be contained in the journals alone. Throughout his career, his moods, ideas and personal critiques were also recorded on thousands of scraps of paper and studies for paintings as well as in letters to family, friends, and colleagues. His complex and layered visual language points to a complex human being. The inner triumphs, struggles, and ambitions of his career are reflected and recorded in his own words and serve as an inspiration for all.

Thanks to generous gifts from the Charles E. Burchfield Foundation and other donors, more than seventy volumes (more than 10,000 handwritten pages) are housed in the Burchfield Penney's Charles E. Burchfield Archives.

Read Burchfield's Journals

In his own words View All

Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, March 12, 1946

The morning sun up full and strong - a robin in the poplar tree just outside the window. B & I to Gowanda to get maple syrup. Pleasant to be out-a fine March day...

Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, March 12, 1946

The morning sun up full and strong – a robin in the poplar tree just outside the window...

Charles E. Burchfield, Journals, Vol. 39, March 13, 1934

...the sight of trains moving back & forth, sending forth great fluffs of steam, made one think “what a wonderful world it is, after all”

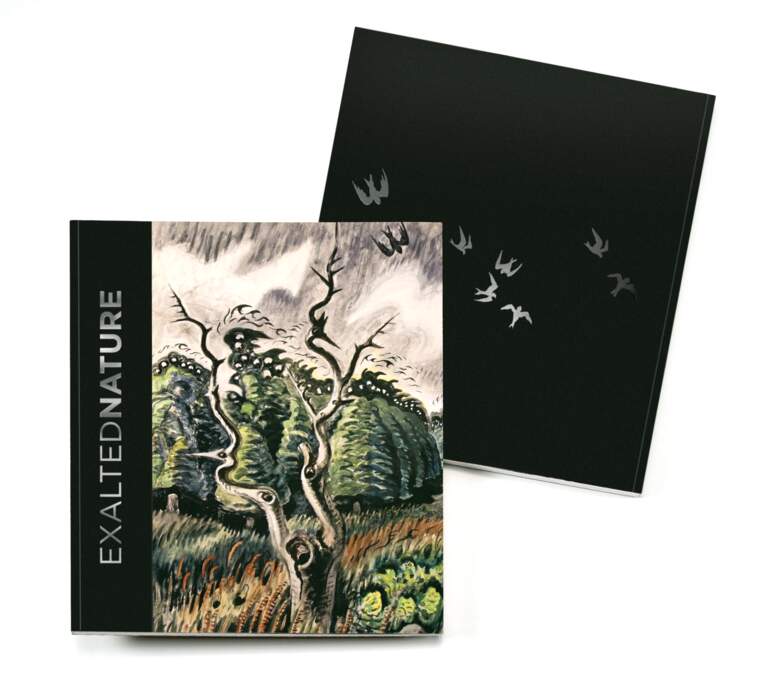

Exalted Nature

The Real and Fantastic World of Charles Burchfield

The beautifully illustrated, 132-page catalog contains essays by both Nancy Weekly, the world's leading authority on Charles Ephraim Burchfield (1893–1967), and Audrey Lewis, the Brandywine's Associate Curator. Lewis traces the origins of modernism in Burchfield's work in comparison with American landscapists. Weekly researched the collegial relationship between Burchfield and Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009), whose artistic family history is preserved and exhibited at the Brandywine River Museum of Art.