Spain: Rock, Roll, Rumbles, Rebels, & Revolution

Past

Sep 14, 2012 - Jan 20, 2013

Spain: Rock, Roll, Rumbles, Rebels, & Revolution is an in-depth career retrospective of the graphic works, iconic characters, and recurring motifs of Manuel “Spain” Rodriguez, the Buffalo-born comic book artist who, in the late 1960s, was a close colleague of and frequent collaborator with the first generation of underground “comix” artists, both on the Lower East of NYC and in San Francisco (R. Crumb, Kim Deitch, Art Spiegelman, S. Clay Wilson, Bill Griffith, Vaughn Bode, et al.) and who,—along with and as much as any of them— profoundly influenced the graphic and compositional style, thematic content, and political sensibilities of two subsequent generations of graphic literature creators.

Although widely admired and long celebrated by both peers and fans in the world of underground comics and graphic literature, this Burchfield Penney exhibition is the first major museum exhibition to showcase Spain as both a proud native son of Buffalo—a city whose then teeming and surprisingly mean streets and factory floors were a formative influence on his life’s work, and one of Buffalo’s most prolific, accomplished, and influential visual artists in any medium.

The exhibition includes both original drawings and reproductions representing all stages of Spain’s comix career (East Village Other, Zodiac Mindwarp, Zap Comix, Subvert, Anarchy, Weirdo, Zero Zero, Blab, American Splendor, et al.), including selected prints from his poster designs for the San Francisco Mime Troupe (1974–2011), with particular emphasis on his mature work of recent years in which he explores both his personal history of growing up in Buffalo in the 1950s and early ‘60s and the global history of conquests, wars, and revolutions in which he has become not only a scholar of surprising erudition but a chronicler and draughtsman of Goyaesque proportions.

Buy Spain-related merchandise in The Museum Store at the Burchfield Penney or online including a catalog featuring essays by Burchfield Penney Art Center Executive Director Tony Bannon, Burchfield Penney Associate Director and co-curtor of the exhibition Don Metz and Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center Executive Director Edmund Cardoni.

“Keep the Flames of Buffalo Burning”

By Don Metz

“Keep the flames of Buffalo burning.” That’s what Spain Rodriguez told me when we spoke in March 2012. His recollections of Buffalo, New York, and the passion with which he spoke of this bohemian town, were inspiring and made me look at his work in a very different way. I’d heard about how much he loved Buffalo, and I had just read My True Story and was awaiting his new book, Cruisin’ with the Hound.

On the plane back to Buffalo, I began thinking about my youth and how much of the material in Spain’s story affected my life. In 1967, when Spain moved to New York City to work at the underground newspaper East Village Other, I was a sophomore at JFK High School in Cheektowaga – a suburb of Buffalo. Coincidentally, it was the first time I experienced a rumble, and with that came the discovery that in any kind of fight, win or lose, there is pain. Fighting for a cause is worth something, but a fight just to have a fight is a sign of painful ignorance.

Around that time, I became more aware of race, civil rights, and freedom of speech issues, and began having long conversations about politics and religion at the dinner table while drinking homemade wine with my father. I know now that it isn’t true, but I remember feeling that I was the only person I knew who thought President Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the Civil Rights Act was a good thing. Soon after , the Vietnam War was in full swing; Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. were assassinated; race riots had burned Watts, in Los Angeles; and Detroit was also on fire.

I, like many, was disillusioned by what the educational institutions were up to. It seemed like the only reason to go to college was to avoid the draft. This eventually led me to underground magazines, protest marches, and conversations with people who were disseminating information at the University at Buffalo and Buffalo State College. One of my most vivid memories of that time was a lecture by social critic and comedian Dick Gregory. He wanted to know why he couldn’t get his sesame seeds at the food co-op. He said to bring the seeds on the same truck that carries dope – “they always get the dope into America.”

I was living what would become part of Spain’s legacy.

Earlier in the 1960s, I skipped school from time to time and took a bus downtown to check out the Hippodrome, one of the oldest pool halls in Buffalo. Unknowingly, I was in tune with Spain. My friends and I even tried to sneak into strip clubs, but that never worked out. It was pretty seedy then, and it was fun to try to get a drink with fake ID and eat Texas Hots and chili while watching the junkies and hookers. I loved those places. And when I was 15, I got a job at the Mars Hotel on Delaware Avenue between Huron and Chippewa – then Buffalo’s “red light” district – and I really got to know the scene.

Back in my neighborhood, there was a bar called Brownies on Ogden St. in South Buffalo, where the Road Vultures Motorcycle Club used to hang out. Their clubhouse was nearby, and a few of us would buy acid from one of them. We knew it would be good because no one wanted to fuck with a Road Vulture. I didn’t know it then, but I was “once removed” from Spain, who was a Road Vulture.

As a kid, I grew up in Cheektowaga, but most of my family lived on the East Side of Buffalo, not far from where Spain hung out. I had older cousins there with cars and girlfriends, and it was your basic juvenile-delinquent-type atmosphere. They got stuck driving me around to make sure I didn’t get into trouble while our parents were doing whatever they did. My cousins had ducktails and engineer boots and would pull over to try and pick up girls or just be assholes to some “squares” from other schools. I remember eating burgers at the Deco 28 diner on Fillmore, which appears in many of Spain’s strips. (I’m not sure that it was the Deco 28, but no one can prove it wasn’t so I’m sticking with it.) So, even though I didn’t know Spain, we did – as was said in those days – “sure chew some of the same dirt.”

When I began working on this project with Ed Cardoni, I was most interested in the fact that Spain drew for Zap Comix. I enjoyed Zap as a college student and I thought it would be interesting to look back at the art form and see how it held up some 30 years later. As I studied Spain’s work, I fell in love with his gift for creating dramatic images that capture moments of recollection to transport the viewer into past experiences. The power of his pen conjures forceful ideas and a sense of fear and righteousness through exquisite drawings. At the core of Spain’s work is the presence of his ideology. How he frames the quest for truth and knowledge, and how uses truth and knowledge as a forum for his stories, is what draws us to him. His stories get processed through highly disciplined illustrations that beautifully depict the plot and characters – characters who thrive on grit, guided by a working-class ethic and driven by literature that reads like poetry.

What’s most striking to me about Spain’s work is his attention to detail. There’s an abundance of it, which is why his audiences spend more time looking at his comics than reading them. That’s a tribute to the artist’s ability to recall and recount visual information and process this information into brilliant storytelling, most apparent in his streetscapes. They are Spain’s masterpieces. They depict a time and place that stirs the viewer’s imagination with mystery and intrigue and captures feelings of an eerie coldness that can be found in any city in America.

I recall a conversation with Erik Hecker, a comic book aficionado who’d never read Spain’s work. I gave him a copy of My True Story, and I was shocked at how quickly he went through it. He said that was because one need not read the words to know what’s going on, since there’s so much information in the frames. Looking back at Spain’s life, one can make some interesting observations about that statement and his aesthetic. His family wasn’t very religious, but they insisted he grow up Catholic and go to church and religious instruction. At some point, though, he decided to go to church on his own. He liked to hang out and observe the architecture. He eventually grew bored with church and stopped going, but after taking art history courses in high school, he returned to check out the art again. Buffalo has some amazing churches, and the North Fillmore neighborhood Spain grew up in had some of the best. It’s easy to see how a kid interested in comics and storytelling could find comfort in looking at these great feats of interior and exterior architecture.

When Spain turned 18, he went to art school at the Silvermine Guild School of Art in Canaan, Connecticut. In an interview with Gary Groth for The Comics Journal, issue number 204, Spain talked about his time at Silvermine. At one point Groth asked, “Did you draw a lot from life?” Spain responded, “I did some, but the thing about comics is, you have to be able to draw from your imagination. When I was in art school we did a bunch of life drawing. As a matter of fact, my first drawing class, we had to draw this concrete block on a table. That was pretty easy. I did the concrete block, I drew the details on it, I did the table, I did everything sitting behind; then, I drew the rafters on top of it, and gave it to the guy and said, ‘Yeah, what’s next?’ So I had this smart ass attitude….”

Attitude aside, from a very early age, Spain’s commitment to excellence made him think about detail and how the details could transform a simple frame into a superb work of art. Again, it’s the streetscapes – masterfully woven into a story with great character and description – that make Spain the unique artist that he is.

Robert Crumb, founder of ZAP Comix talks of his admiration for Spain’s ability to capture these details. Crumb said “One thing I always admired about Spain was his attention to background detail. Those beautiful cityscapes and stuff he could do, and he loved to just, like, capture these detail of the urban landscapes. The signage on Mission Street and all that stuff. I love that in his work.” Well said. The streetscapes feel as if they are an homage to the human struggle. I like to call them Altars of Discontent. What’s gratifying about them are the stories that they represent and how Spain sets up his sequences in a manner that gives the streetscape its essence. Whether in the beginning, middle, end or standing alone, the majestic magnitude of the images Spain creates provides a sense that these are places of honor and importance to the characters, having themselves earned the right to be there.

Comics are a multimedia sequential art form, and one needs to evaluate Spain’s sequential movement as well as his draftsmanship. Sequential art is the province of art and literature and poetics and sound. Spain’s knowledge of poetry is apparent in his work, fitting words into a balloon in comics that produces literature like lines of a poem. In one bubble of a Trashman strip, Spain’s most iconic character, the text is laid out in such a way as to make it hard not to read it as a poem, a vernacular poem, a concrete poem:

TRASHMAN

EMBARKS UPON

A SERIES OF

MEDITATIVE DISCIPLINES

DESIGNED TO HEIGHTEN

HIS REACTIVE INSTINCTS

THIS PARTICULAR ONE

KNOWN AS THE

“RED DOT TECHNIQUE,” SHARPENS HIS

RESPONSIVE PATTERNS

DURING PERIODS OF

IMMINENT DANGER

ENABLING HIM TO

GRASP INSTANTLY

COMPLEX SITUATIONS

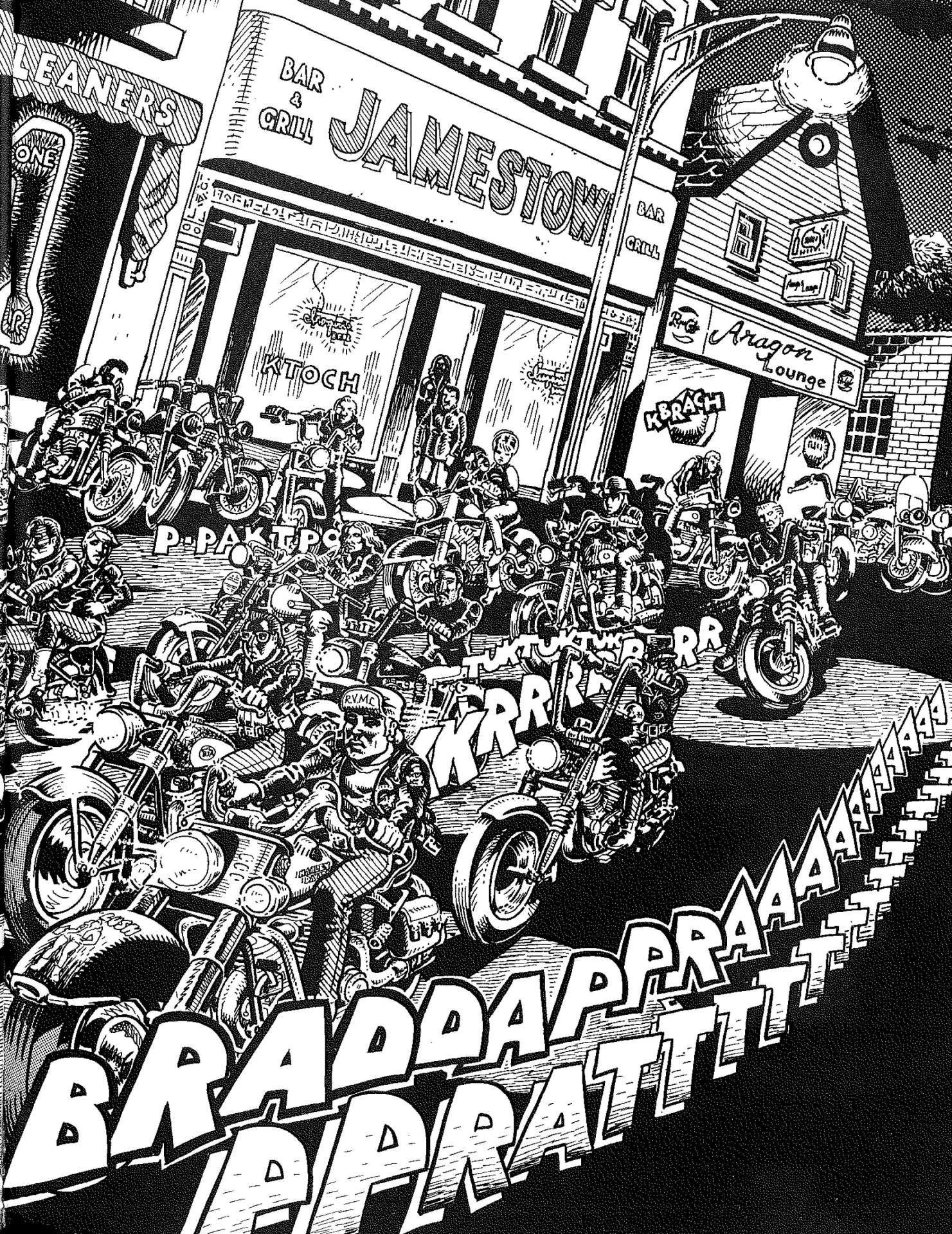

In another instance, Spain creates lines in captions that are each accompanied by an illustration. The setting of this sequence is the “Jamestown” (a bar in Buffalo, now called Nietzsche’s) in his strip Hard-Ass Friday Night.

Somebody comes down

Hard on the fourth step.

Soon everybody takes up the

Beat until the joint resounds

To the sound of dozens

Of Stomping feet.

An off-the-wall remark

Provokes violence…

Inevitably, it spreads quickly.

The setting and the poetics come from Spain’s Buffalo roots. He is often known to brag about being from Buffalo, and he observes that Buffalo is a bohemian city. He tells of his involvement in the counterculture, but thinks of himself as a beatnik. Evidence of his interest in poetry is found in The Fighting Poets from his recent book Cruisin’ with the Hound. Spain begins to recite the classic poem To Helen by Edgar Allen Poe, in defense of a waitress being sexually harassed by a patron and friend of Spain’s. The sequence is brilliant. It opens with a large frame – two-thirds of a page – showing Buffalo’s Watt’s Restaurant, with typical Spain detail right down to the crumbs on a plate with a half-eaten burger. Jocko, a local hood who is harassing a waitress named Helen, says, “howz about if I put a liplock on your love muscle.” Unfettered, as Jocko continues the pestering, she walks behind the counter where we see Spain eating a barbeque pork sandwich. He turns to Jocko and says, “Say, Jocko…Why don’t you SHUT, THE FUCK, UP.” Spain then turns, stands, and begins to recite the before-mentioned poem to the waitress, when he is pelted by “the remnants of a B-L-T sandwich.”

The next three frames are dazzling. He points to Jocko, points to himself and finally points outside. It’s classic Spain: Open with a beautifully detailed illustration that captures a moment in 1950s America. Create a conflict between a bully and a seemingly helpless victim. Use large, bold typeface for a third individual shouting, “SHUT, THE FUCK, UP” to create silence in the next frame. Give comfort to the victim through poetry, and draw a rise out of the bully. Then, once again, use silence with minimal movement to demonstrate to the oppressor that he won’t get away with this shit.

Spain is one smart, hard-ass motherfucker. He is and always has been a working-class artist who – with his fists and with his pen – has stood up to government, religion, corporate thugs, bullies and anyone else who would, in Spain’s words, “spread tyranny across the land.” Through the process, he creates brilliant images that capture the imagination and spirit of the righteousness he believes in and convincingly transports these emotions to the viewer.

When I first met Spain in the spring of 2012, I asked what Trashman would look like if he drew him today. This is what he said:

“I would love to do Trashman today. If I was doing Trashman today, one of the devices I would use is have some general who marches on Washington and declares himself president. And that would be the shadow of tyranny that falls on the land. In a lot of the latter Trashman episodes, that’s kind of like poorly defined. And then I would have some multimillionaire whose kind of behind him and then uses all these devices of rigged voting machines to suppress the vote and all this stuff. All these neo-fascists that call themselves republicans who are trying to pull the wool over our eyes. This next election will be real interesting to see. You know there are all these hopeful signs, but you can never tell what some clerical fascist like Rick Santorum or Sick Santorum …”

Makes you want to “Keep the Flames of Buffalo Burning."